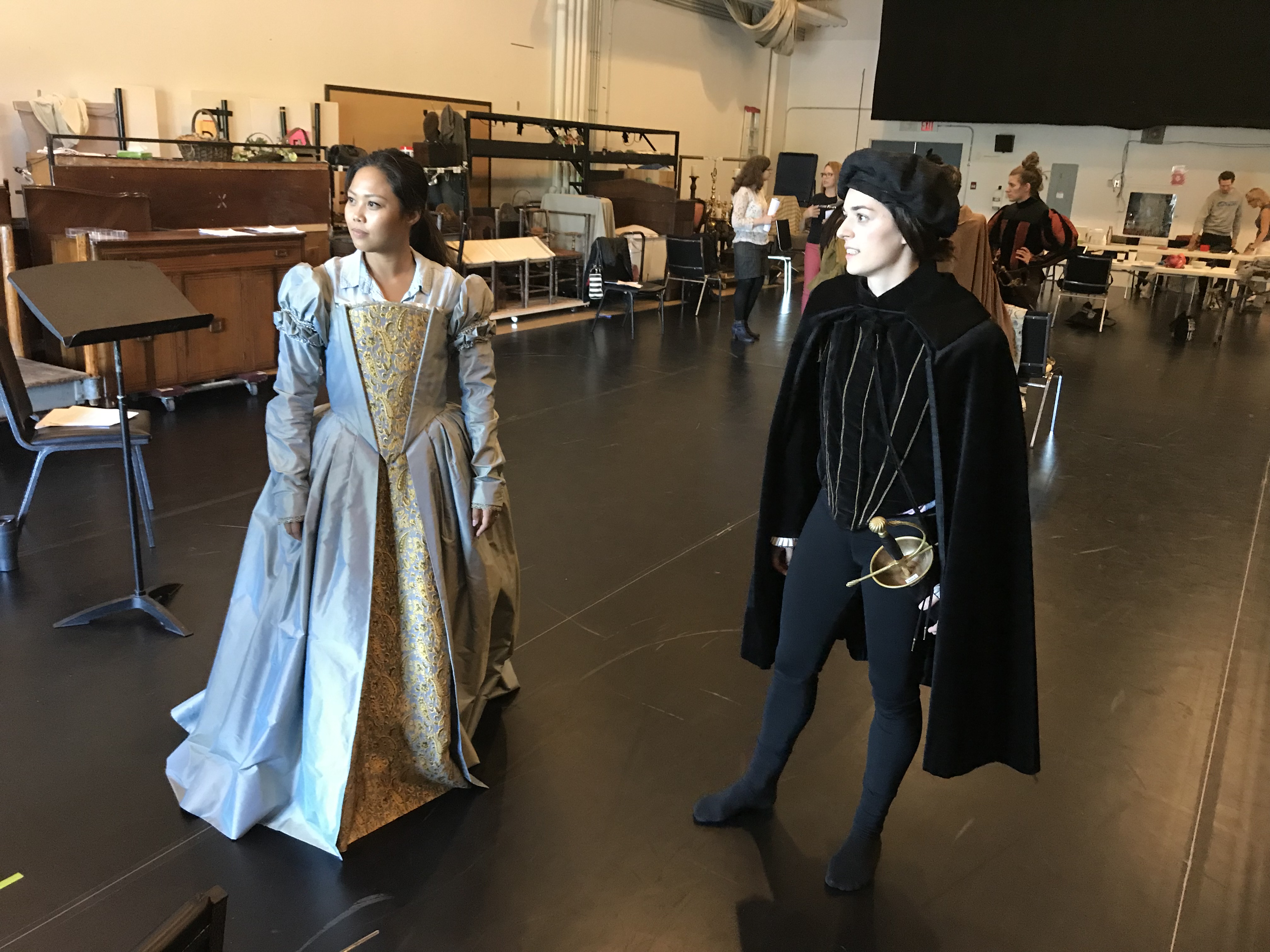

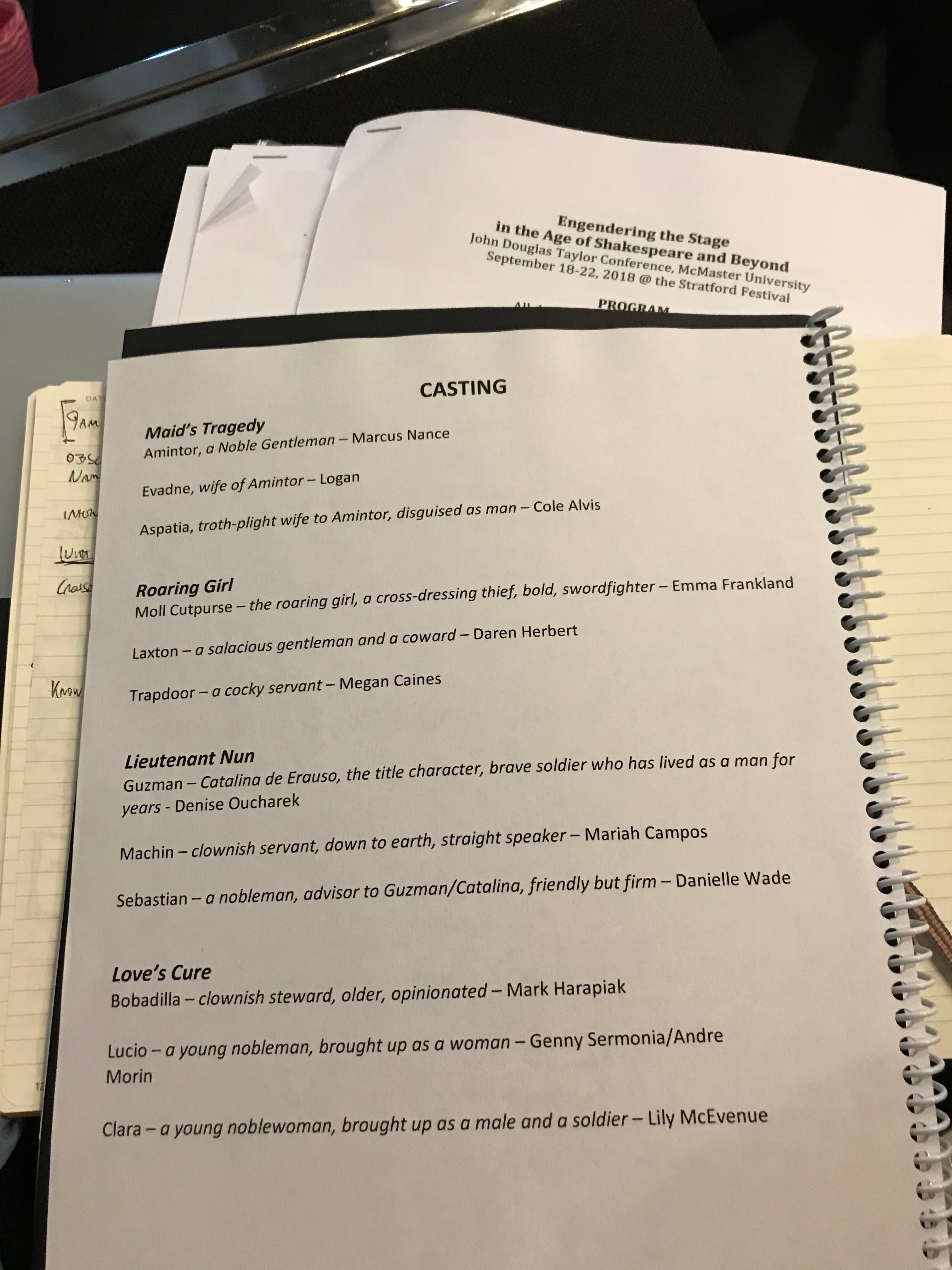

Our last post offered reflections upon a week of practice-as-research work at Stratford Festival Laboratory. This piece follows the same style, of collaging responses and thoughts about the project and its week of work last September [2018], meditating upon potential uses, problems, and future applications with such work. These are issues the project continues to discuss; on 17 March 2018, for example, Melinda Gough will lead a roundtable at the Renaissance Society of America that picks up on some of the issues addressed here.

***

MAC TEST: I would love to adapt this sort of thing for my own work—in the classroom, and bring it to whatever conference I might be invited to: “let’s do this!” And I do bring—where I work at Boise State—I’ve brought actors in for week-long workshops putting on plays, and things like that, and now after this experience I feel I can say “hey, let’s do this workshop” and make it research-based. … I think the most amazing thing has been the circle group and people speaking their mind—“checking in,” as Gein identified it. That’s probably been the most impactful moment. It’s been useful as a scholar to hear the actors speak from their point of view; it’s very different to how we speak as scholars. With PaR you have the actors and the scholars together in that same place, speaking about the same issues, but from different perspectives.

ZOE HUDSON AND STEVE PURCELL. We very much valued the opportunity to observe and participate in this workshop. We were struck by the levels of trust and openness that the week had established between the participants, and the commitment that everyone involved brought to the work. Participants were thinking and working very deeply, rigorously examining both the texts and their own instincts and interpretations. The week had also fostered a mutually respectful dialogue between academics and practitioners. […] We would have been interested to hear a bit more about these rehearsal room shorthands and methods of communication; participants alluded to “Oops, ouch” and “checking in and checking out,” and we wondered whether it might be useful to produce a written summary of these sorts of guidelines which could be circulated to participants in future workshops. The main insight for us was that it is vital in projects like this that academic participants are seen, and see themselves, as part of the ensemble; it is equally important that the practitioners involved are respected as thinkers and researchers in their own rights and not merely as hired hands putting the academics’ ideas into practice. This was something […] that could be profitably disseminated to a wider audience.

ELLEN WELCH. I think the really helpful thing [about] thinking with performance is that performance I find very future oriented… One of the things Keira [Loughran] said very early in our session is that if a particular performance fails that’s okay because you learn things to bring to the next one; I think that’s a really helpful way for academics to think about our work too. I think there’s always this pressure to have a conclusion, at a really basic level, a conclusion to whatever essay or book that you’re writing, and those are the parts that are hardest for me to write, because it feels like closing down—it is a closing down. But that’s always the goal of the genres that we write in, to get to that conclusion. And I wonder if there’s a way we can think about our work more in this future-oriented way in which the ending is an opening towards other things, that you could try at another point in time. So it feels more processual, and less that I’m producing a product.

NATASHA KORDA. [Responding to Ellen] That’s really helpful. I also think about performance as future-oriented, and as a means of connecting history to the future in the present, which can sometimes involve what we loosely call archives. But how you construct your archive is itself performative, because you’re always doing it in the present moment: archives are not static things, they’re constantly being made and remade. There’s something really hopeful—sometimes not, sometimes destructive—but at least there’s the possibilityof something hopeful, in that remaking of the present, which is really exciting, I think.

[…]

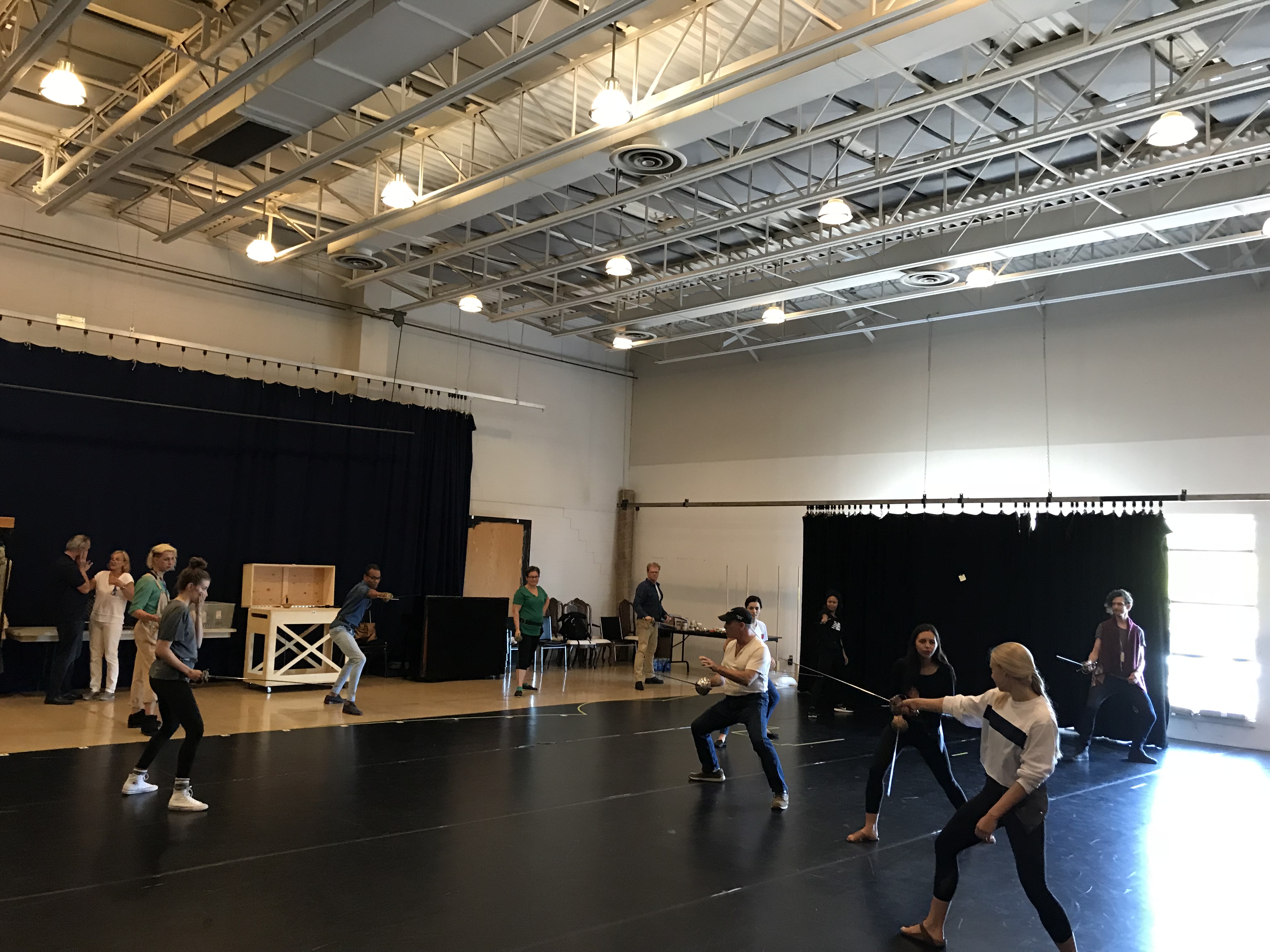

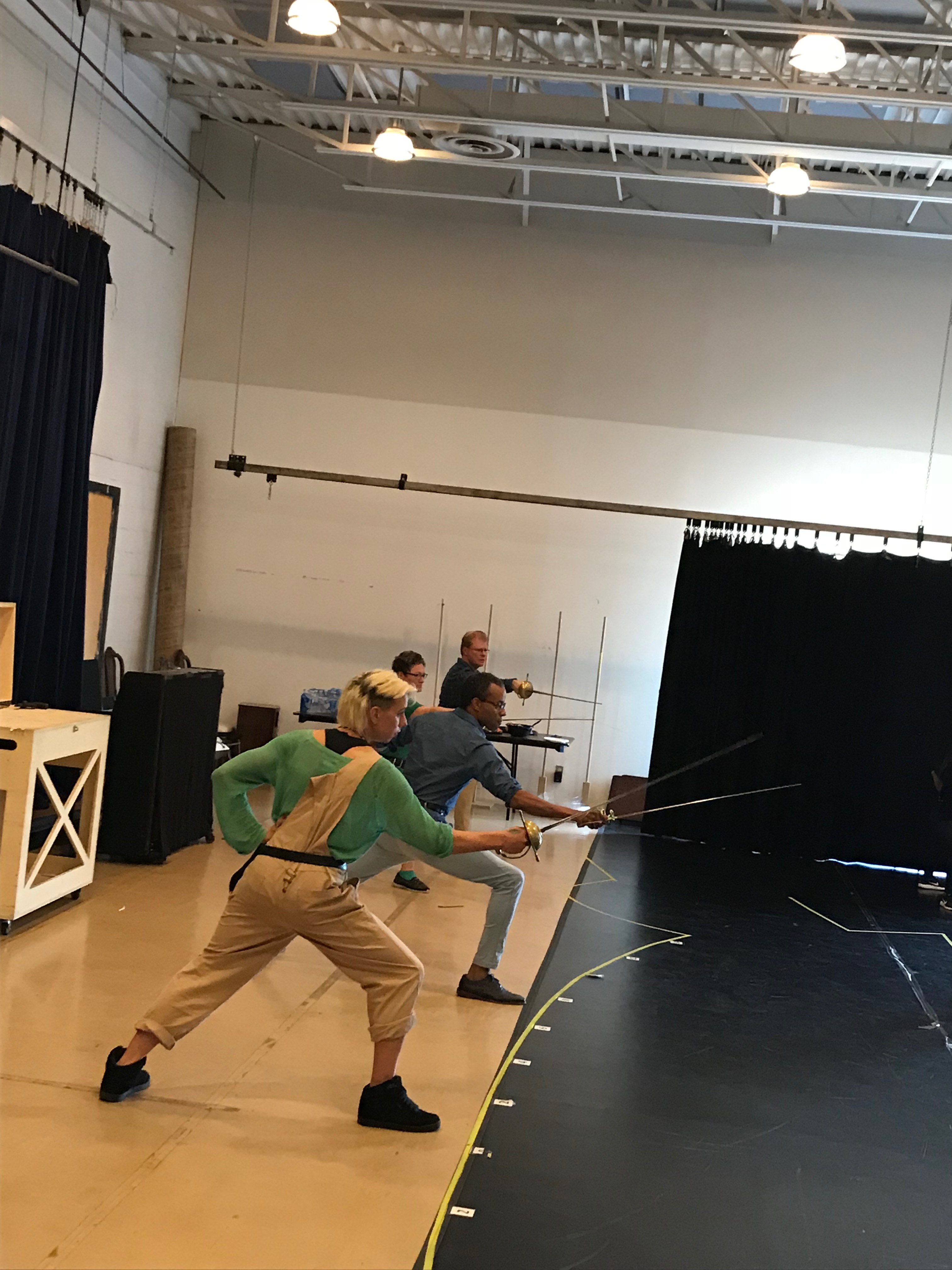

It’s not the case that people in the past were simply more repressive or patriarchal or racist than in the present. We still have all those things now, they took different forms in the past. That’s a real challenge in our present moment, both in performance and in teaching texts about sexuality and gender in the early modern period—there’s a lot of violence in these texts, violence that we often want to avoid in order to focus on the more hopeful aspects of the text. But it’s equally important–and powerful in performance–to connect the violence of the past to the present, to make its ongoing presence felt. I think, it’s better to think carefully about how to do that than simply to say that we shouldn’t perform these texts because they’re violent and they’re misogynist. There’s a lot of violence and misogyny in texts that are written now, in the present, and that are part of our performance culture, so I think it’s all a question of howyou stage them.

COLE ALVIS. One of the things I’ve come to learn… come to know, is that there were trans and non-binary people in Shakespeare and pre-Shakespeare times. And this notion that wherever we are right now is the pinnacle of where we’ve been trying to get is not true—or [because of] the way Canada talks about itself on the world’s stage it is likely to only see stereotypical versions of Indigenous peoples. The “status quo” does not represent everyone—and does not for the past either. And just because I didn’t learn about these worldviews in school, it doesn’t mean that they weren’t there.

PAMELA ALLEN BROWN. This idea of the “art” of playing is something I’ve been thinking about in my scholarship, but it’s great to hear people calling themselves “artist”—it’s a different word to “player” or “actor”, and I think words do matter, obviously, to us, so… […] That’s one thing that’s struck me. Also the division between scholars or academics or whatever we’re called and the players or actors is not really bridged. I take the point that what they [actors] think they’re here for is different from what we think we’re here for… but that can be a creative friction, and I think it has been. I just think we’re here for a very different reason than they are here… Frankly I’d love to call myself an artist too! The PaR model itself makes me envy actors who can justify doing that, and forces us as scholars to be modest and take a back seat. Not sure that’s entirely good in an increasingly anti-intellectual world, however. And while I learned and felt a ton more than at other conferences, I did get the message that working scholars should learn from actors working, but vice versa, not so much. Among other points, the impact of the Renaissance diva, a woman artist, got lost in the shuffle, ironically enough… How might the group improve actor/scholar interplay in the future?

ERIN JULIAN. When the question was raised about what we’re trying to do here, I felt a little bit uncomfortable at the fact that the actors seemed to have this idea that they’re doing something for us… and I would like to think more about how we might do things for them. And one of the things we might do is give them tools for doing this work that they’re often trying to do now—trying to explore these questions about gender, trying to explore these questions about race, on a contemporary stage. That can be risky work. So I was just noticing that there were a few moments where the actors were asking ‘what are we doing for you?’—I’d like to see us thinking about what we’re doing for them…

ELIZABETH CRUZ PETERSEN. [I found it really valuable] to have artists like [Gein Wong and Emma Frankland] come and work with us through physical exercises that prepare us to collaborate with the actors, [including] exercises on gender awareness and on embodiment so we can get a sense of what the actors go through, as far as training and warming up before a performance. This is especially important to me since my scholarly work focuses on somaesthetics, which is all about the unified body and mind, its complete embodiment.

CLARE McMANUS. One of the really clear results of this [workshop] is that this work pushes us to articulate our methodologies and to do that responsibly. That is [something] that is shared with other disciplines, editorial disciplines: you know [in] editing, for instance, very clearly, [that] you have to tell the reader what your methodology is. And so this morning we did a call-in/check-in to make sure everybody actually understood where we were all coming from. And actors’ voices around the table have really pushed us to really articulate why it is that we are here. And I think that fundamentally is very, very important. And so one of the direct results of this is sending us back to our methodologies and making sure that we have a clear and appropriate articulation of whatever that may be.

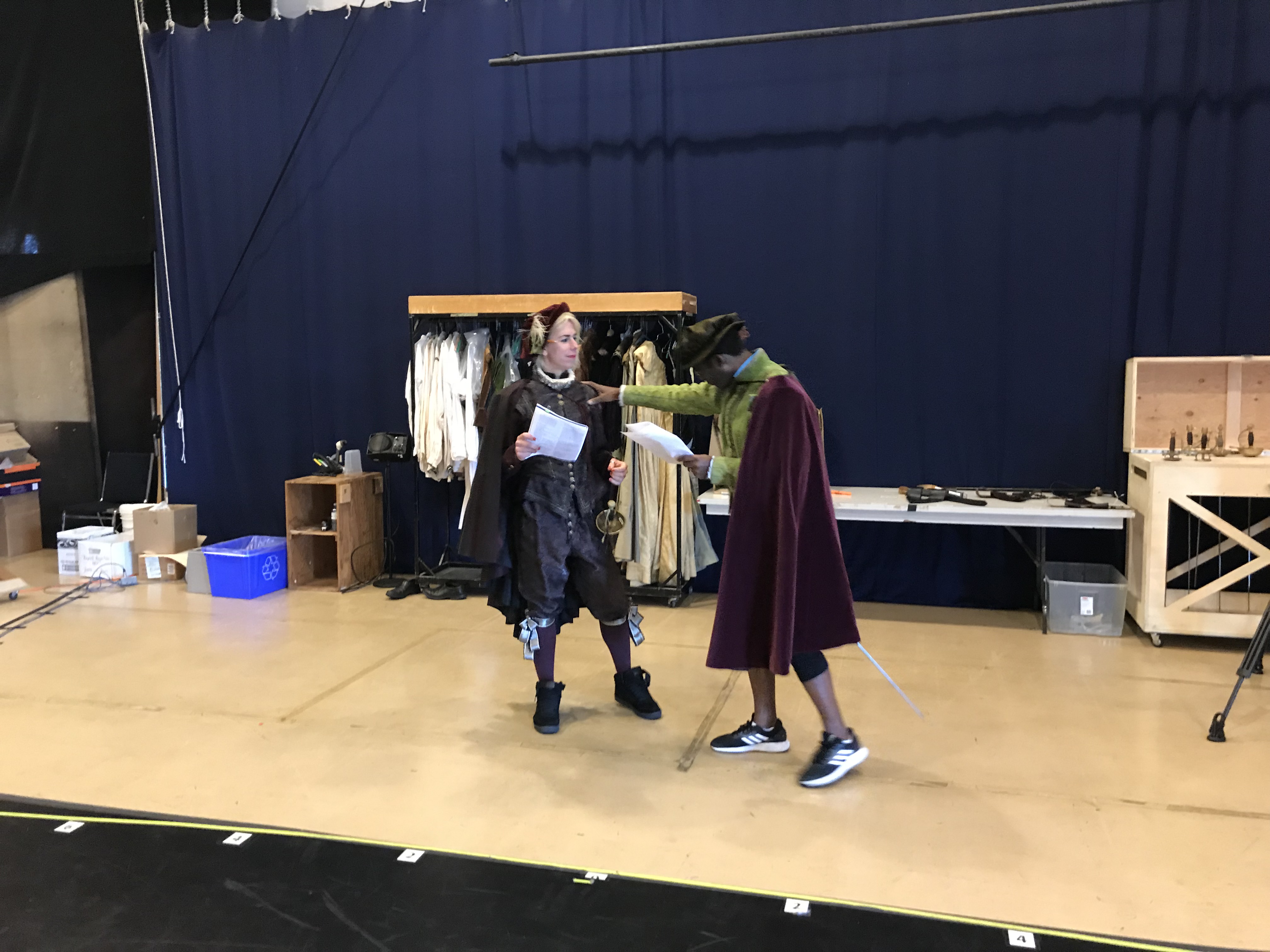

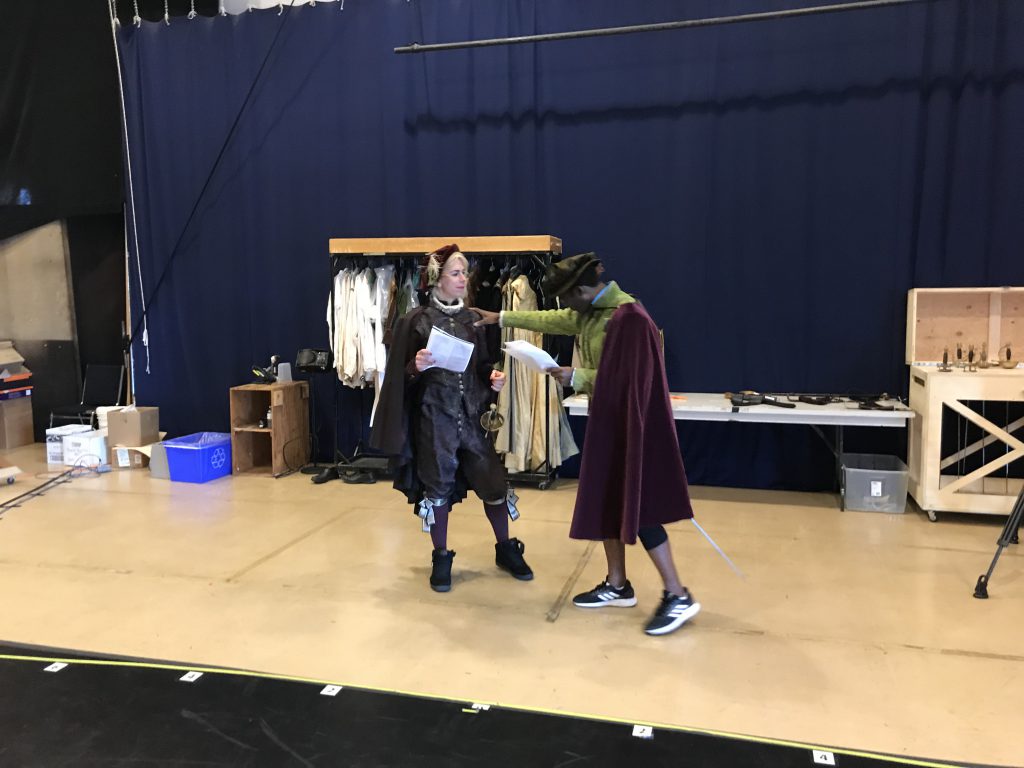

ROBERTA BARKER. One thing that hit me yesterday was what must have been the huge contrast between Richard Burbage and [the actor who] we think [was] his apprentice, Richard Robinson (who I was working on), when they possibly created the roles of Amintor and Aspatia [in The Maid’s Tragedy]—what that working process was between a master actor and his apprentice (who perhaps was 13 or 14 years old), and how Keira [Loughran], as contemporary director, and Marcus [Nance], and Logan [Brideau], as contemporary master actor and 14-year old emerging actor—the process through which the three of them were working on the scene we were working on; what’s shared there and what’s not shared there. And what’s uncomfortable for us that was completely cool in 1611—and perhaps what was uncomfortable in 1611 that we’re totally cool with today. So I think the way that that encounter—that’s not always a comfortable encounter between the early modern text and this history of performance, that we’re trying in some way to recover and figure out (because we don’t have all these documents and all this evidence that we have from later centuries); the relationship between that history and that journey of discovery that a lot of us are on as scholars, and the journey that one goes on with actors with these texts: the way they rub up against each other can be so […] productive.