Our third day was a mixture of exploratory discussion and play—in its various forms. I feel it’s important to reiterate the way that the workshops have been structured so as to enable time and energy for open conversation. We’ve been beginning (and ending) with “check-ins,” which give everybody space to articulate their thoughts and share what’s on their mind. Gein Wong has led these processes and their modelling of the practice has helped create a room in which openness and warmth have felt like default views. This method has been instrumental in creating an open and protected space that enables generosity and allows for vulnerability for everybody in the room, while keeping us all in constant dialogue. Our opening check-ins then move into open, fluid discussions about the research at hand, the scholarship underpinning and responding to the performance workshops, and the impetus for the afternoon’s work.

This way of “working” might seem like an addendum or “warm-up” to the performance workshopping, but as almost everybody has remarked, it’s in fact integral to the explorative nature of the play that “practice-as-research/PaR” or workshopping generally is about: this is the process; this is the learning. Here’s a call for more spaces, more default personal and work environments, that are able to bring together personal state of mind, openness, and dialogue as the fundamental basis for what we do and how we do it.

What is it that we’re doing here?

In discussing the prompts for today’s workshopping, discussion moved onto some of the important and often unaddressed questions about work with classical texts. Do we need to recover plays entrenched with misogyny, homophobia, and racism? How much should we resist and rewrite or even discard texts that do not work for us today? These are crucial questions that extend to the whole period Jamie Milay’s call to bury Shakespeare on Day 1. As some participants observed, these texts and the structures they come out of also contain many of the complexities and oppressions still at work today; our world is also entrenched with misogyny, homophobia, and racism, and thinking about the nuances within the plays we’re looking at this week are also ways of negotiating the present.

The past’s not dead. It’s not even past.

Moreover, as Emma Frankland articulated (better than I can paraphrase here) these texts also offer histories that are often marginalised or erased—trans histories, racial histories, LGBTQ histories, more. The work we’re doing in these workshops thinks about how these histories can be discovered or represented in combination with contemporary experience—negotiating, in other words, the way texts-in-performance necessarily bring together past and present. For instance, we thought about what it might mean to have queer or genderqueer characters explicitly assert their identity within a text. But we also talked about what it means when these individuals in plays are framed as figures of comedic fun. This sense of tone is crucial to questions of representation. Pamela Allen Brown pointed out that humour itself can be a powerful form of agency and is not necessarily a sense of ridicule. Finding a line between pathos and jest is an important ongoing question for exploring the complex identities of these dramatic characters.

I am Aspatia yet.

Thinking further about these ideas of identity and respect for the characters in these texts, Roberta Barker observed how powerful the line “I am Aspatia yet” in The Maid’s Tragedy can be when viewed—as that group has been exploring—from a genderqueer perspective. The Maid’s Tragedy group has been thinking about the possible gender non-comforming identity of Aspatia, and Roberta noted that the workshopping and the performance research of the actor exploring Aspatia presents a character who has throughout the play had to respond to other people’s manipulation of their selfhood (has Aspatia been gaslit throughout the play?); here, they assert their sense, as Roberta put it, of “I understand who I am”: I am Aspatia yet.

I’d print it in text-letters.

Another thing that came up around the table in the morning was discussion of editing and translating practices. As I mentioned in yesterday’s blog, Edward “Mac” Test is working on an ongoing translation of The Lieutenant Nun and so his edited scene, excitingly, remains in flux in the room (*live editing klaxon*). Natasha Korda is also in the midst of editing Twelfth Night. These plays contain both cross-dressing and trans characters and both deal with the complexity of gender identity.

When will we have a trans edition of an early modern play?

Discussion arose, springing out of questions of feminine/masculine first-person endings in Romance languages such as Spanish, about how to manage gender-identifying speech in translation, as well as how editing texts more broadly can take account of genderqueerness. As Natasha pointedly observed, there is some history and scholarship on feminist editing practices but almost nothing on trans editing theory. One important part of this process is to bring trans voices and expertise into the process of editing. This particular question of editing points more broadly to how scholarship can develop more inclusive methodologies, and beyond collaborative process these issues are yet another example of why a more diverse academy—including trans editors—is urgent and important.

Let this strange thing walk, stand, or sit…

(RG 1.1.254)

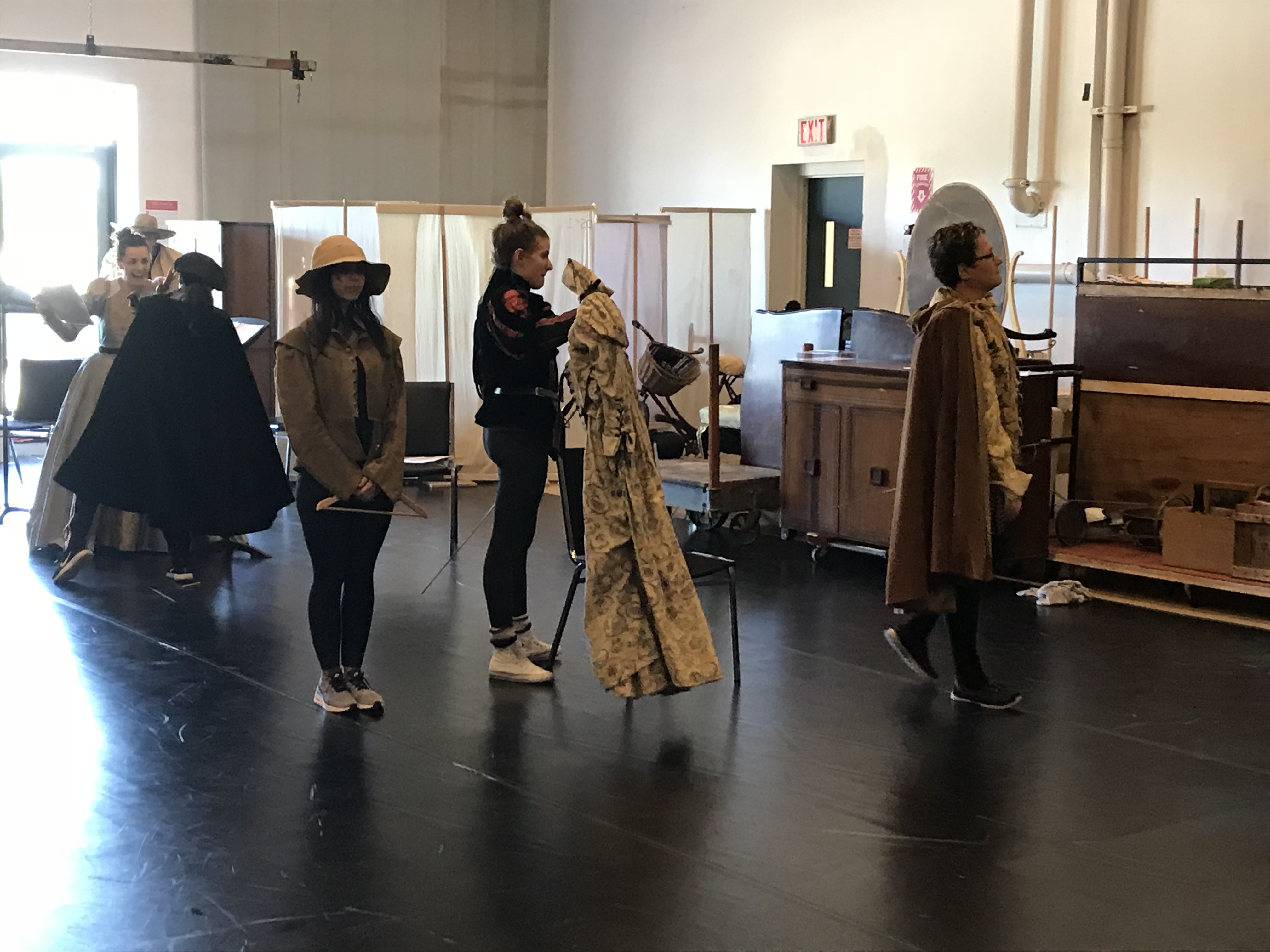

When we got onto our feet, we were led in another movement workshop by Peter Cockett. This involved thinking about descriptions of gendered gait in early modern England, while also being attuned to the fact that such descriptions—as gleaned from plays, conduct manuals, and various other print descriptions—are open and in no way witnesses to early modern walking. At the same time, we were led to think about different styles of walking: walking on toes or walking on heels. Natasha Korda explained how shoe technology shifted very quickly in the early modern period and in the period around the late sixteenth century, the time in which the heel became a new standard part of a shoe. The development of the heel shifted the way that people walked, from walking on toes (with flat-soled, “sock”-style shoes of the medieval period) to walking on heels in more robust shoes…

We thought about how we moved around the space, on toes, holding carriage smoothly (again channelling the likes of Castiglione’s Courtier and its advice on decorum). That’s astonishing when considering the chopines that crop up, for instance, in The Lieutenant Nun: as Mac put it, imagine walking in these!:

We were also encouraged, as per Clare McManus’s reminder, to be mindful of the fact that there were not strictly gendered ways of walking, comportment, or carriage—particularly when we look at the period’s history not through Castiglione’s court life but through vast and varied performance histories. These include, for instance, female tightrope walkers and tumblers who do not necessarily wear restrictive clothing that forces a particular gait or a particular way of holding oneself.

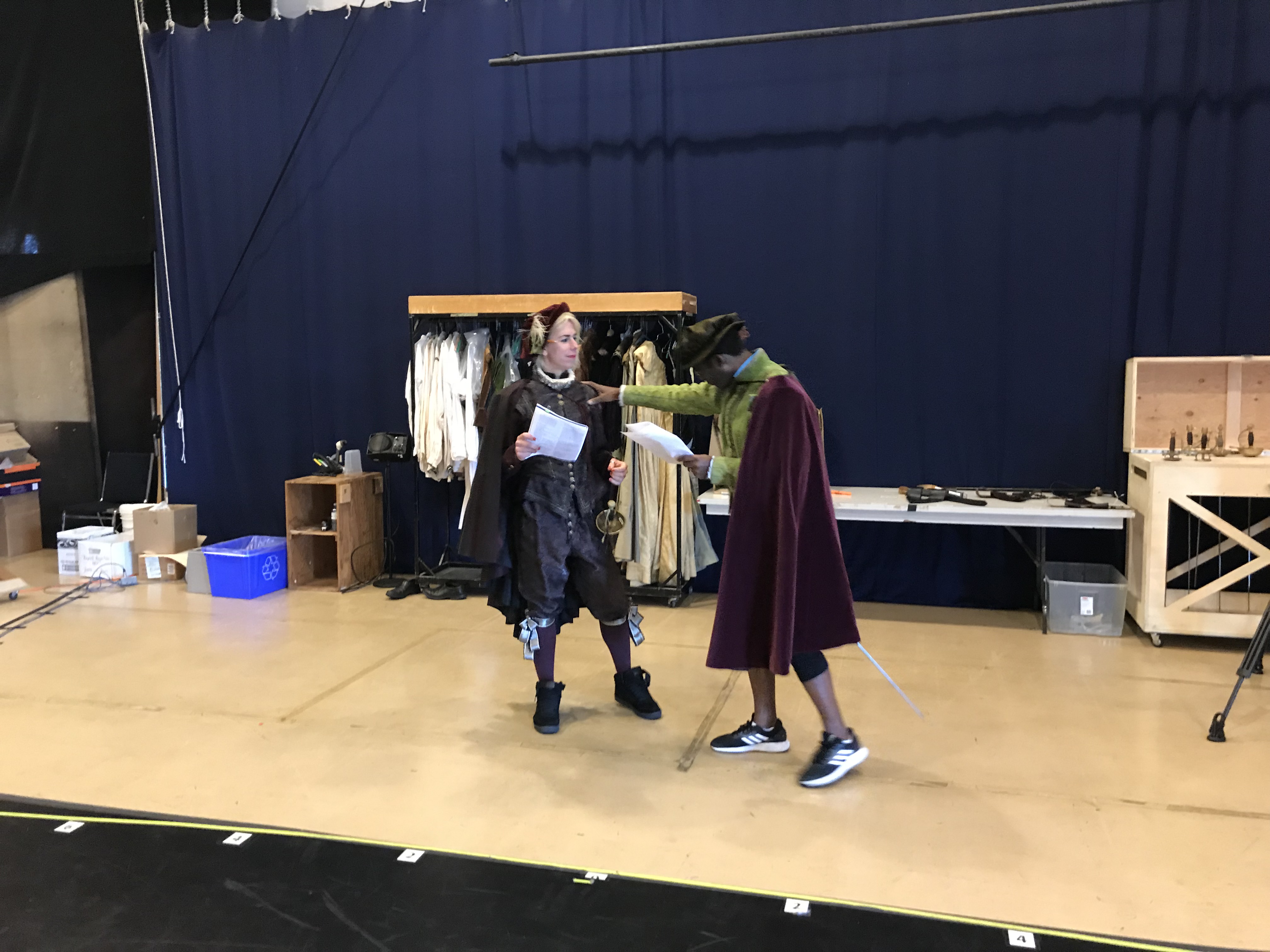

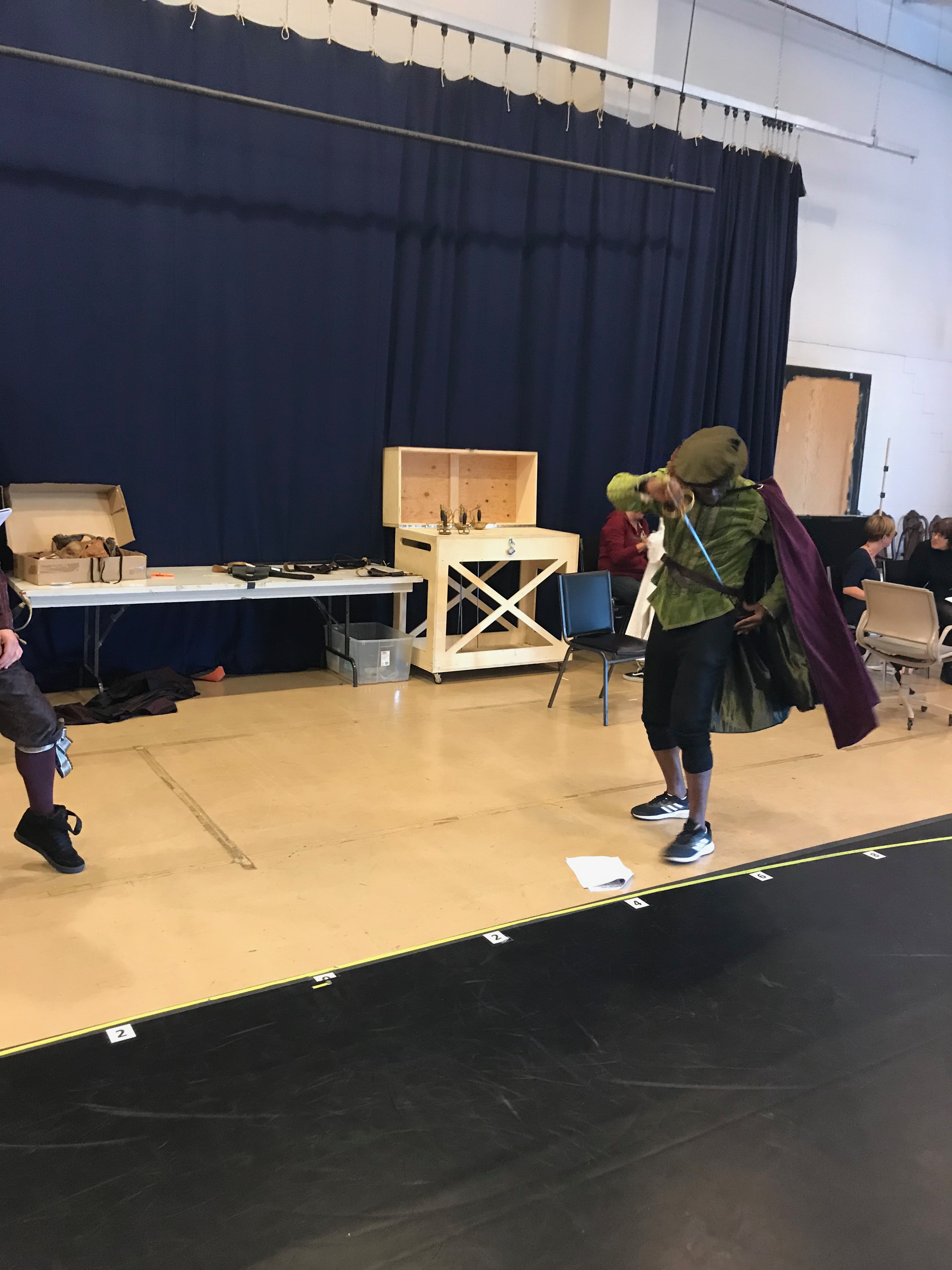

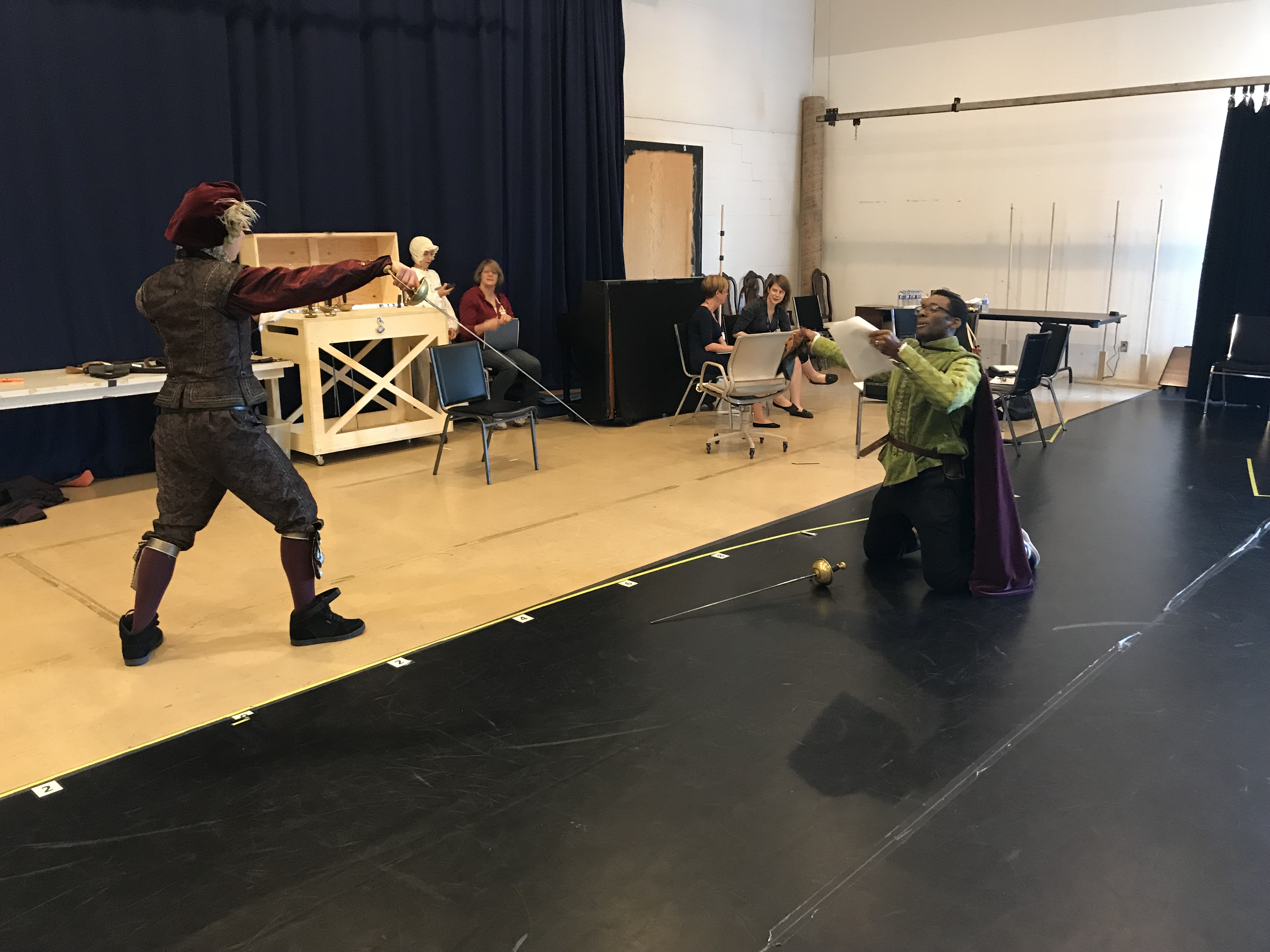

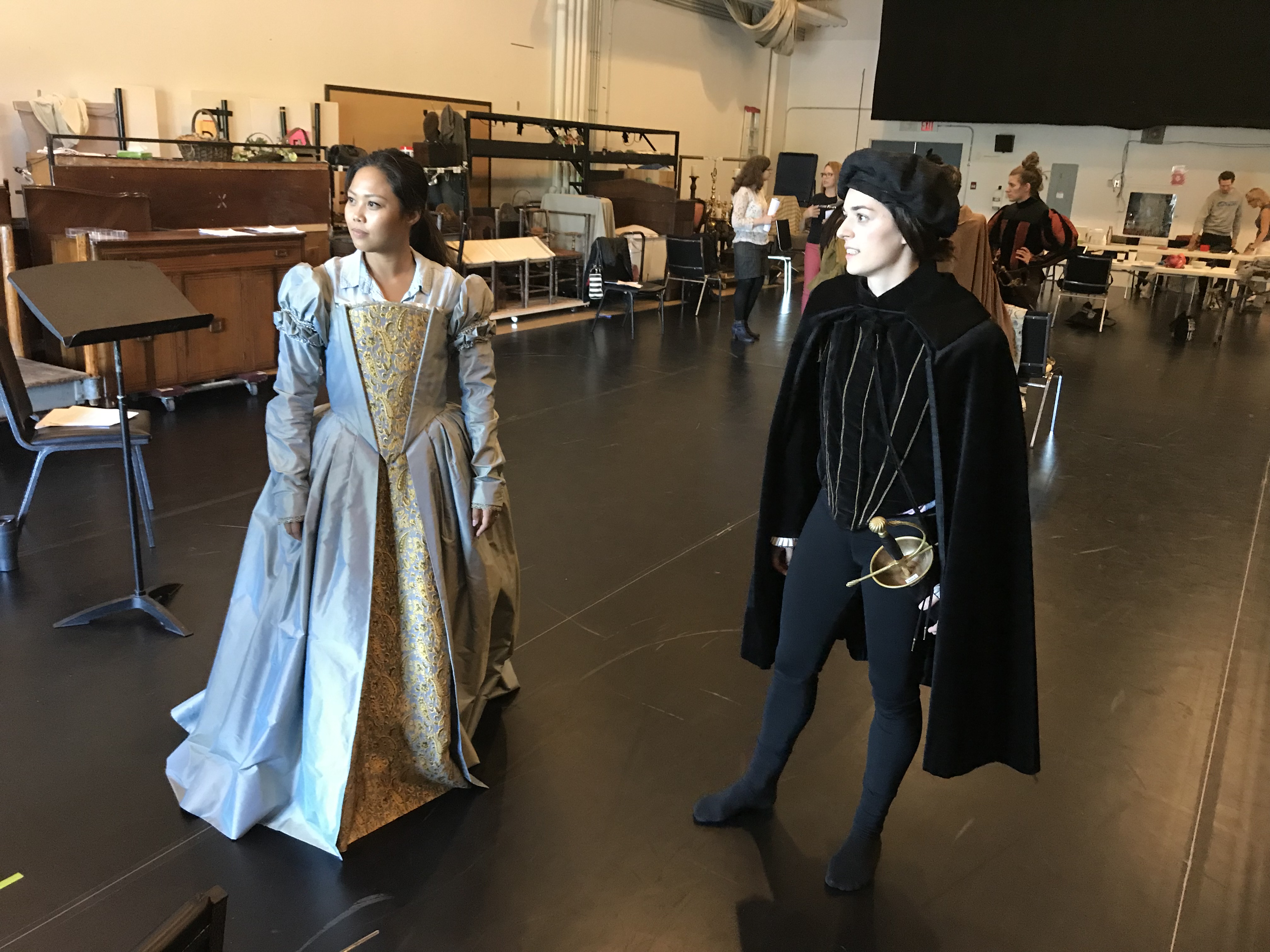

Our walking exercise thereby opened up ways of shifting between decorums and between movements that are multigendered. We went into a catwalk-style “walk-off” in a circle, bringing in two different characters from the plays and asking them to walk at and alongside each other: how do relationships work when viewed through carriage and walk? This was an astonishing exercise in physical ingenuity and play with power. Cole Alvis playing (or “walking”) a darting and slinking Aspatia moving around a stately and solid Amintor (Marcus Nance) was a virtuoso double-act in movement that showed how power inheres in both strong, direct, upright stance and gait as well as in shorter-stride, winding, indirect movement. This extends, too, to technologies involved in walking—not only the shoe but the sword, which can be held as Amintor showed forcefully at one’s side with a hand, or offered like Aspatia in snaking movements to one’s counterpart in a display of comic self-sacrifice that tellingly held equal theatrical force…

These exercises therefore begged the question: what other ways might there be for thinking about character identity beyond verbal articulation? How can an actor find ways of performing an identity—including working with gestures and walks that are a part of our own way of being in the world—without presenting as an entirely different (and sometimes problematic) identity that might on the surface seem part of characters from classical texts? How can we find ways to bring oneself into performance while also playing to, with, and against the various historical modes of decorum that helped produce a playtext? In suggesting that there are multiple decorums available to early modern performers and thinking about how they might translate to performance skills today, this aspect of our workshop struck me as just one particularly powerful example of how theatre history and performance can combine to offer a wealth of performance techniques that are at once true to contemporary subjectivities and in dialogue with historical experience.

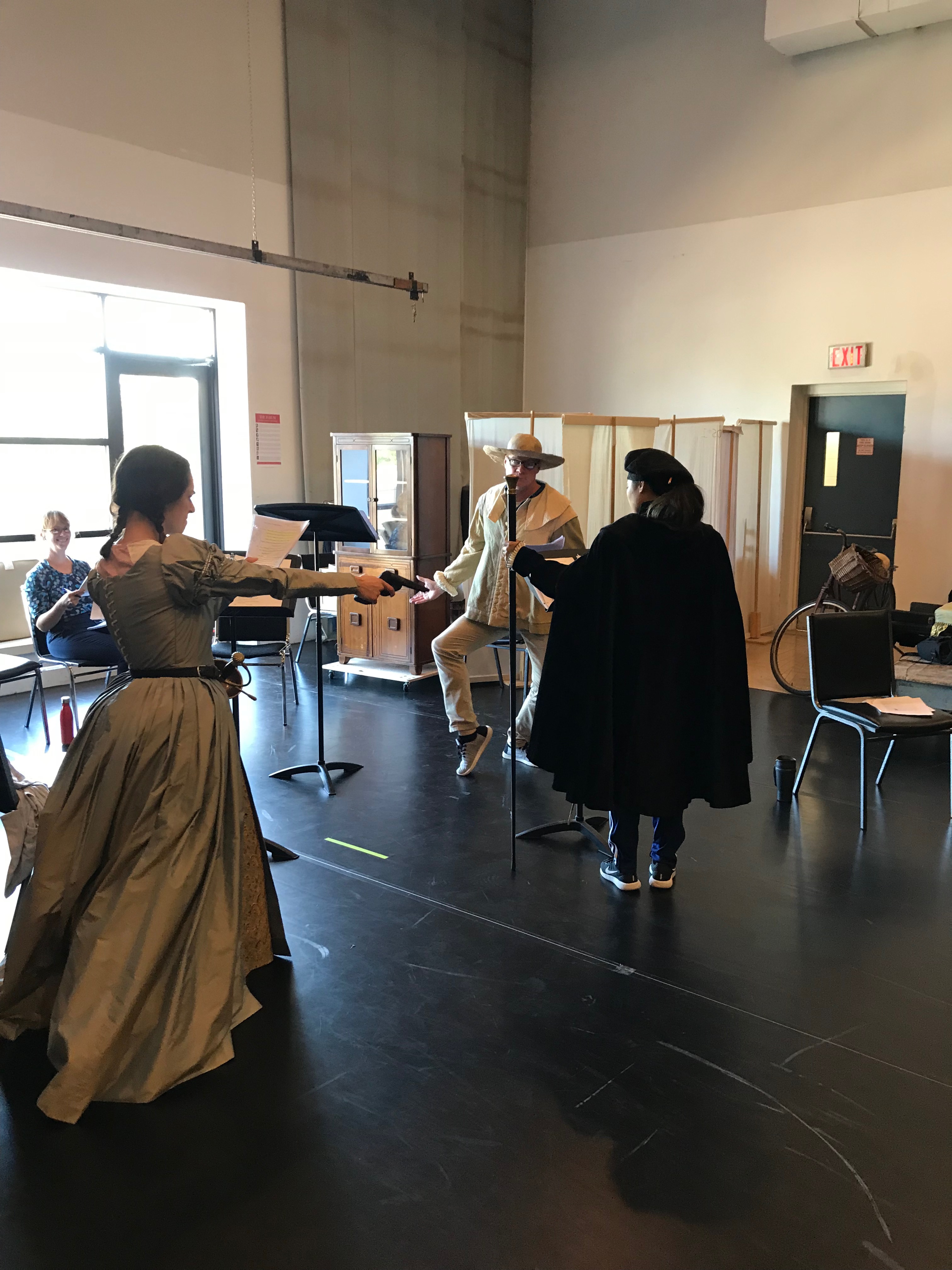

We finished the day by exploring our scenes further and offering the opportunity for sharing. It feels important to end this post by underscoring the centrality of process, of ongoing development and experimentation, to these workshops. It is in discovering and testing that we can find possibilities for future practice and glimpses of both scholarly and performance insights. Acknowledging the disjunction of finishing a blog for Engendering the Stage with… Shakespeare: the play‘s the thing…