For our second day, we’ve been putting our scenes for Love’s Cure, The Lieutenant Nun, The Roaring Girl, and Maid’s Tragedy on their feet, beginning with movement in and around space that goes beyond thinking in masculine/feminine binaries and moving towards not only the embodied experienced of characters but their apparel-ed experience…

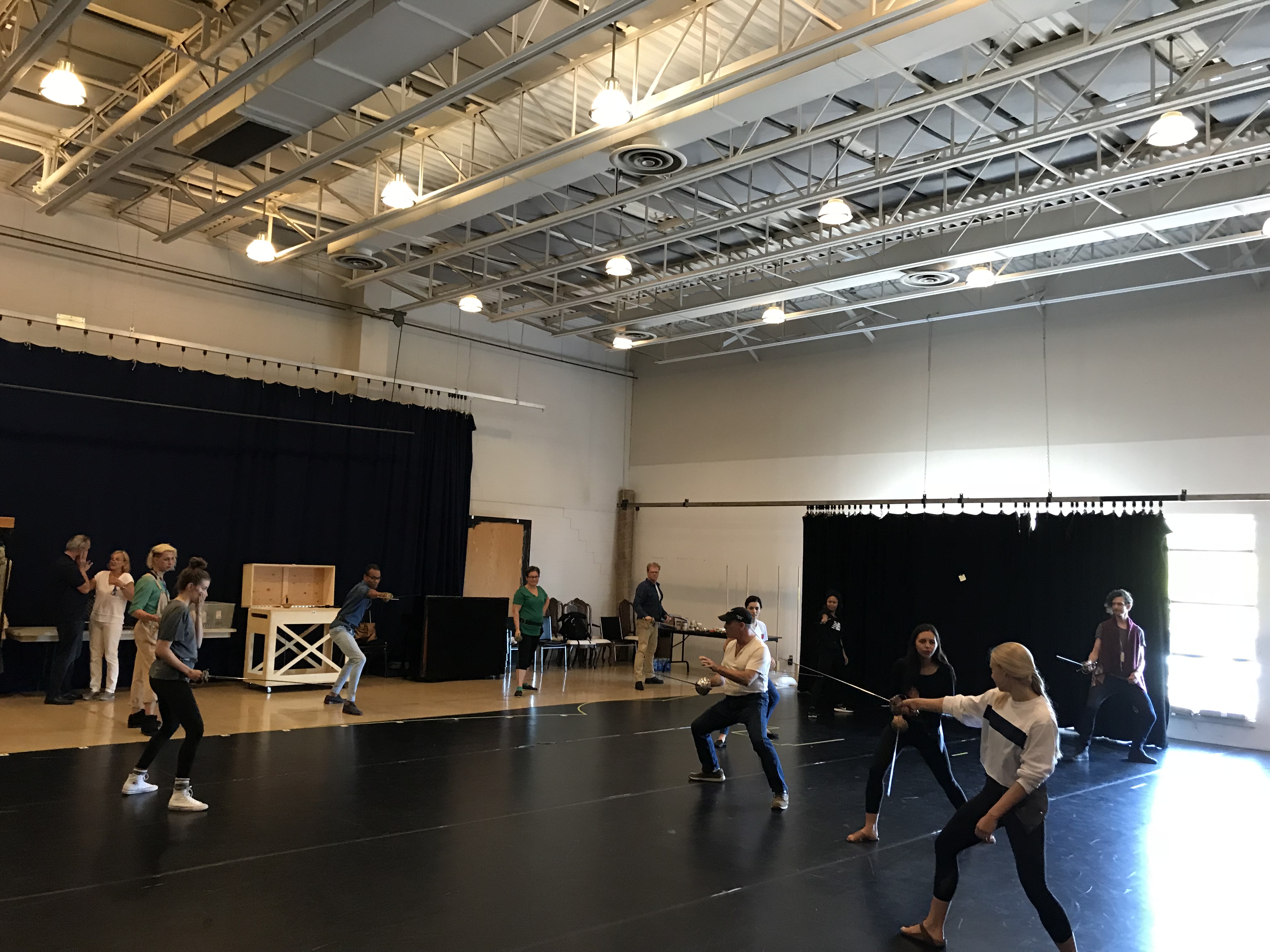

After checking in, we moved into movement exercises led by Keira Loughran, making sure we were all present in our bodies, aware of our physical place within the room.

Light/Heavy; Direct/Indirect; Sustained/Sudden

Peter Cockett then led us into some of Laban’s movement exercises (Laban Movement), which in this case moved between three different binaries of movement, sometimes in combination: moving light or moving heavy, moving direct or moving indirect, moving sustained or moving sudden. Peter used Laban’s method to introduce us to a vocabulary and series of movements not articulated by masculine/feminine binaries. The language of Laban can thereby provide alternatives to describing and/or embodying character without reference to gendered assumptions or ascriptions—are they going to walk directly in this moment, might their body language be sustained or sudden, and so forth?

This exercise also brought different characters out in each of us, making us conscious of our presence, gait, and posture and aware of the different forms of abstract, presentational, or naturalistic movement we might inhabit. As different combinations were issued, we were all forced to think about our momentum, the space we take up, and our negotiation of other human bodies.

There’s way more to a “text” than a text.

After working on this movement, we moved into thinking further about the week’s scenes in respective groups. As groups worked closer with the text, in readiness to thinking about embodying characters, discussions arose about how to negotiate one’s own identity within a text that offers many possible identities for a given character, while also restricting others. How do twenty-first century individuals approach historically-estranged characters? Are there modern subjectivities already inherent in these texts?

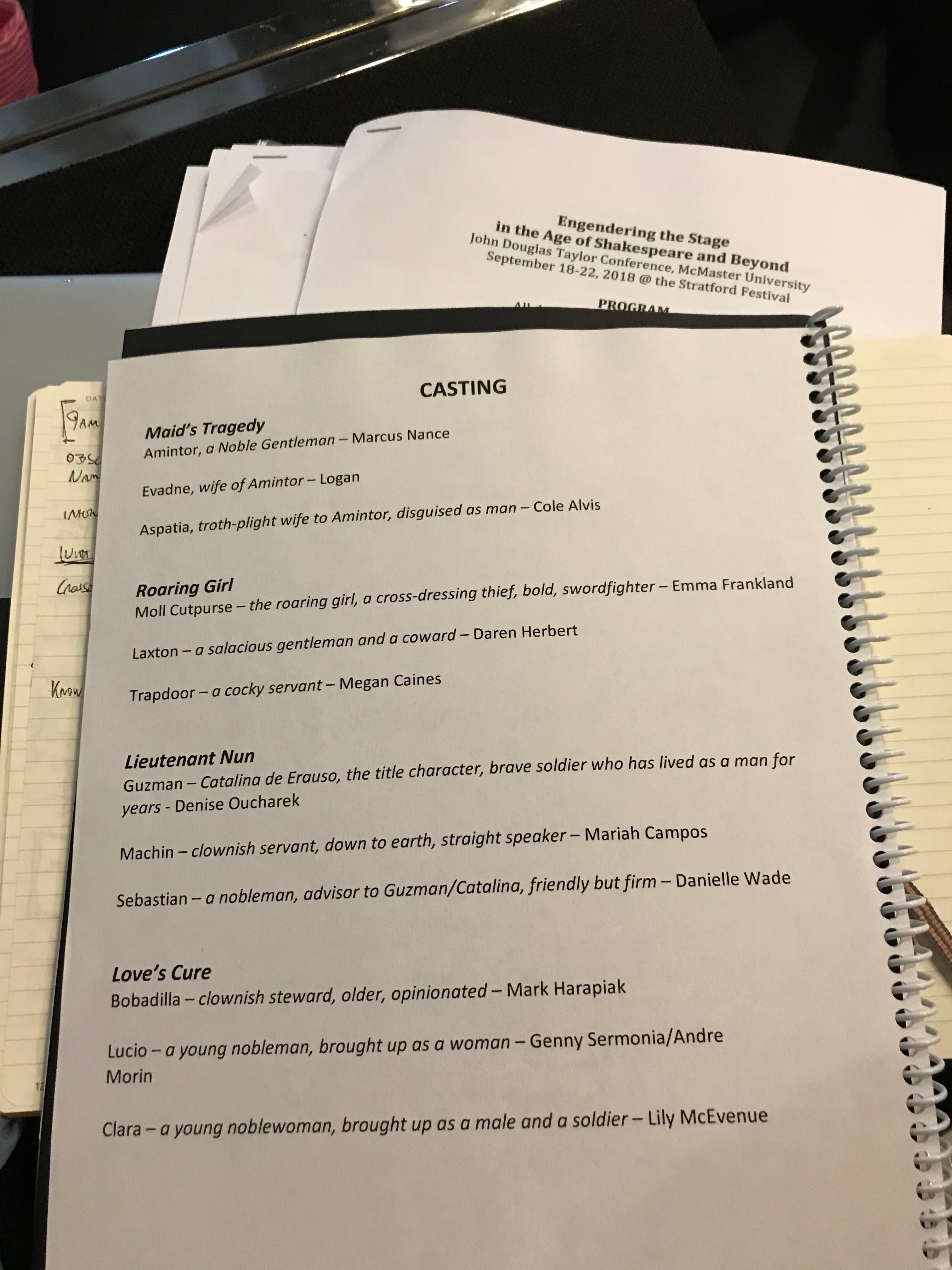

These discussions were particularly acute in moments where the characters themselves are dealing with questions of personal identity, the ways they are read by others and how they might pass as one or another gender, and at moments of identity assertion. What might it mean for a cisgender woman to play Guzman in The Lieutenant Nun—a character (based on the real-life Catalina de Erauso) who was born as a woman but who spends most of their life dressing, and largely identifying, as a man?

What agency can be found in Moll’s fluidity in The Roaring Girl: she is a title character who can move between gendered identities. But what is her relationship with her body—and so with the body of the actor playing Moll? Would that actor cast themselves in this role, and if so, why, and if not, why?

The Maid’s Tragedy too offers possibilities to think about the identity of a (female identified) character like Aspatia, who in the final scenes of the play dresses as a man and confronts her former lover. Can we find in Aspatia a gender nonconforming identity? Performers variously remarked how valuable it is to be able to take one’s own identity into a classical part—whether it’s an implicit or explicit part of the play, or not. In working flexibly, for instance, with the pronouns assigned to a character, performers can find moments based on lived experience that can shift ways of thinking about the play; at the same time, it also offers a way to work in perhaps more productive ways with what’s on the page.

Black is thy colour now…

These questions are also pertinent with regard to race. For instance, the language of blackness in Renaissance plays, as the work of Kim Hall and others has taught us, is always fraught with racial politics and, often, an articulation of deep-seated structures of racism and white supremacy. How do we navigate racially charged lines in performance and particularly in process/rehearsal work such as these workshops? Such lines read and are received differently depending on who they’re spoken by and to whom they’re spoken. These textual difficulties have no easy answers, but they prompt urgent questions.

These texts are not historically performed things.

These thorny issues raise the subject of “adaptation”—a focus in our closing conversation. But do changing the pronouns in a text, for example, constitute an adaptation (or, for that matter, leaving them but playing within and against them)? As Emma Frankland reminded us, early modern texts are notoriously unstable beasts: they are not theatrically sanctified products and they are by nature adaptable. Why don’t we think of ourselves as players any more, Emma asked, and what have we lost in that shift to “actor”? In feeling free to play—in a whole host of ways—with text, we are doubtless recovering some of the very theatre history that is at issue in our explorations this week. For Edward “Mac” Test, who is currently translating The Lieutenant Nun to English from Spanish, these questions of adaptation and play are particularly pertinent, as he has the licence to amend words, phrases, and registers—partly in response to theatrical developments in the workshop. What might be gained and what might be lost, for instance, in ignoring the gendered word endings in addresses during a scene of dialogue? In translation, the relationship between playtext, adaptation, and play is always at issue.

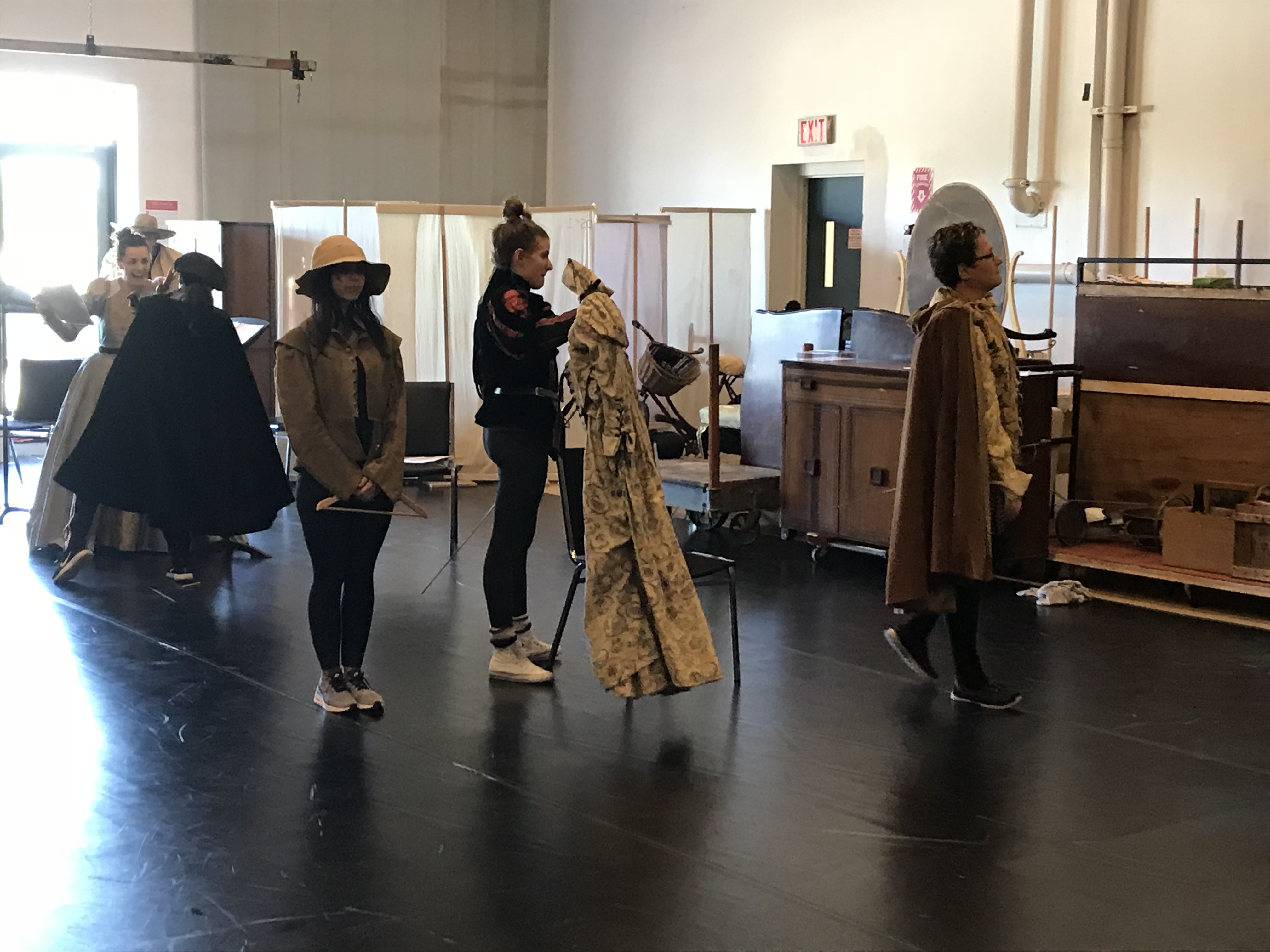

Something popped in my head putting on the costume: the weight of clothes, the layers, having the sword or weapon

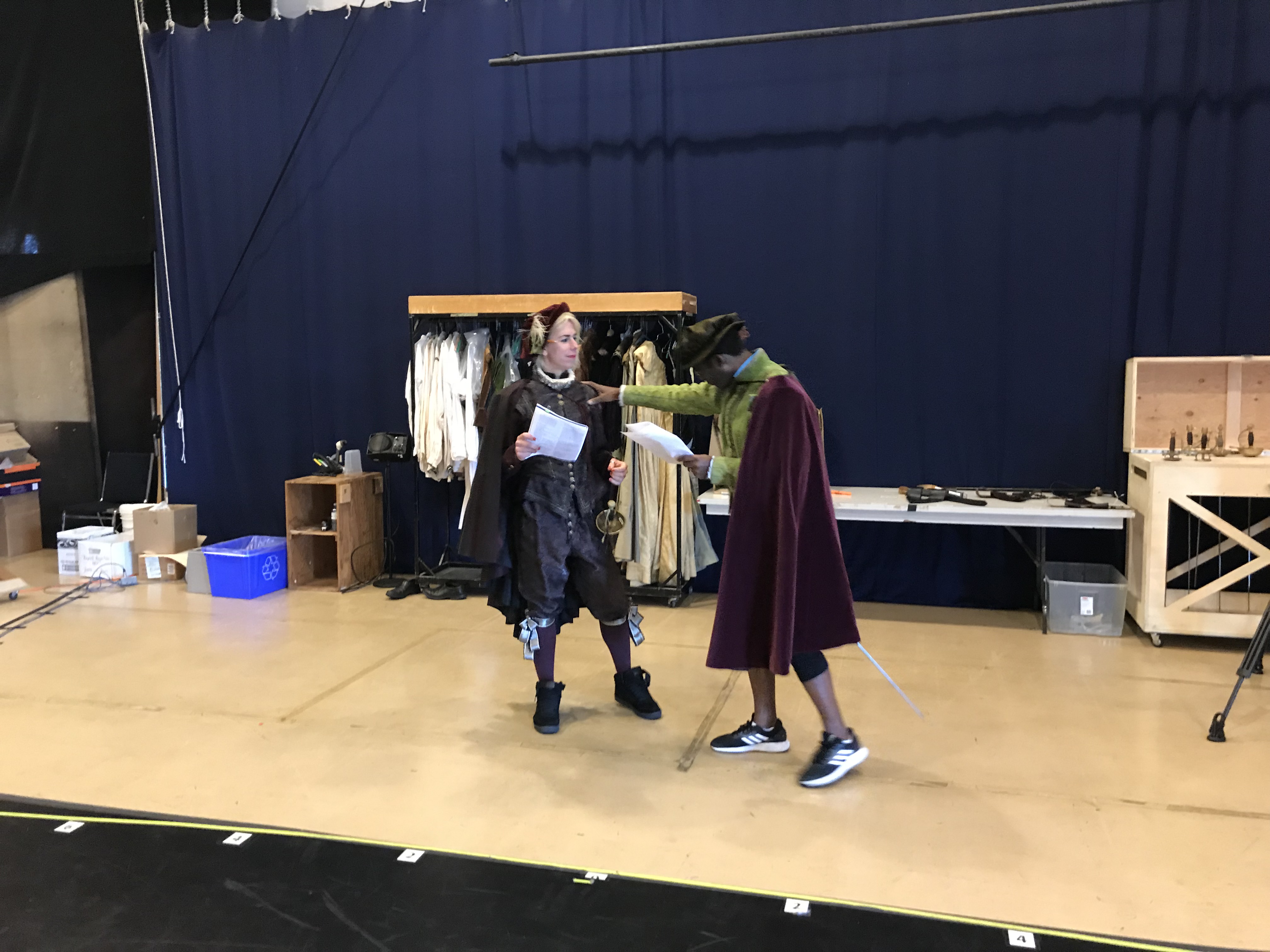

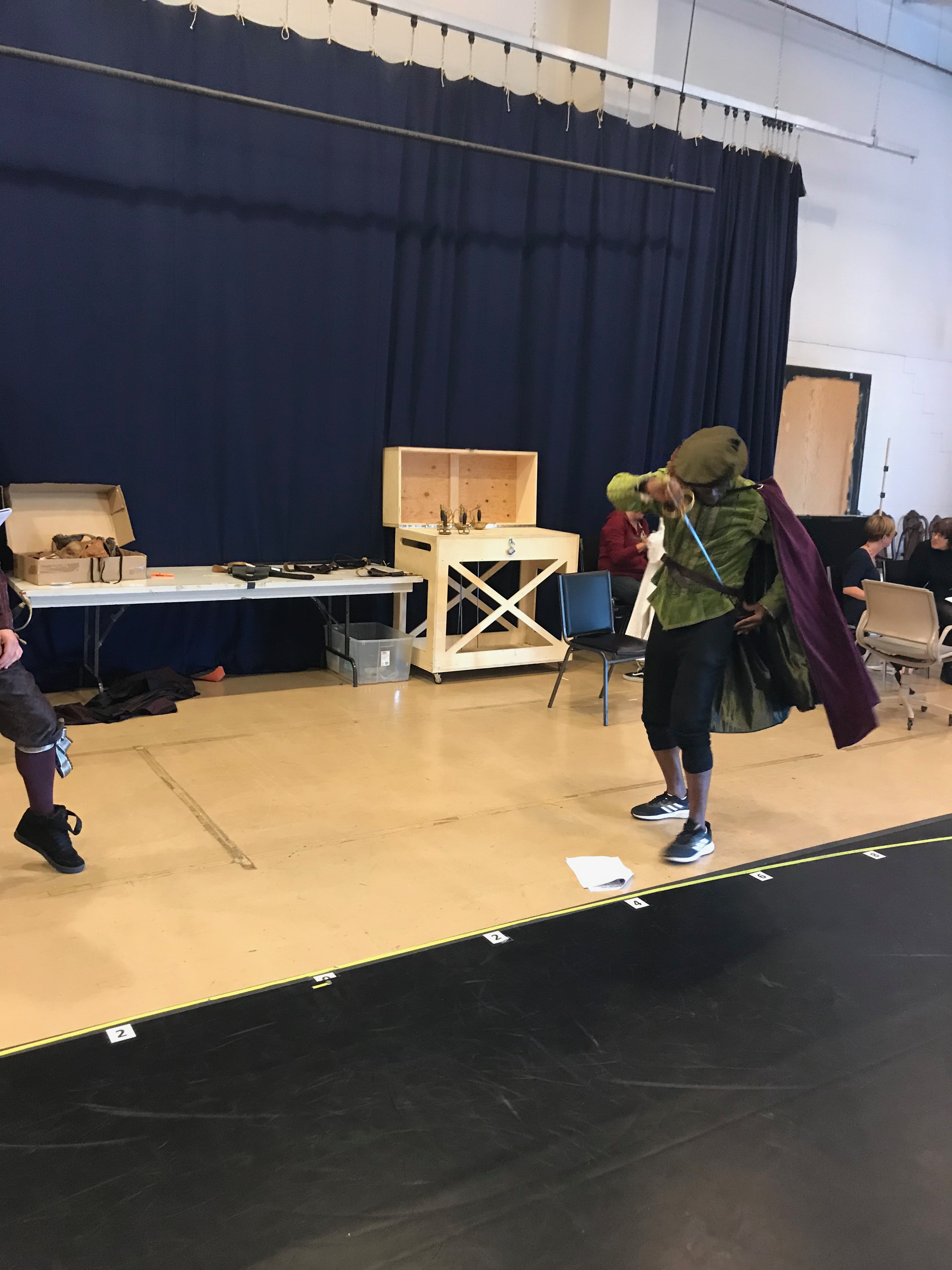

As actors gradually found their way into costumes, energy levels soared and the scenes began to stretch across further space, scenes overlapping. Noticeably—as someone moving between groups all afternoon—I was struck (almost literally) by the amount of costumes and clothes flying around the room. After hours of considering how individuals are variously gendered in different ways, it was curious to see scenes in which garments were shrugged off, tossed away, and launched across the floor in acts of identity assertion.

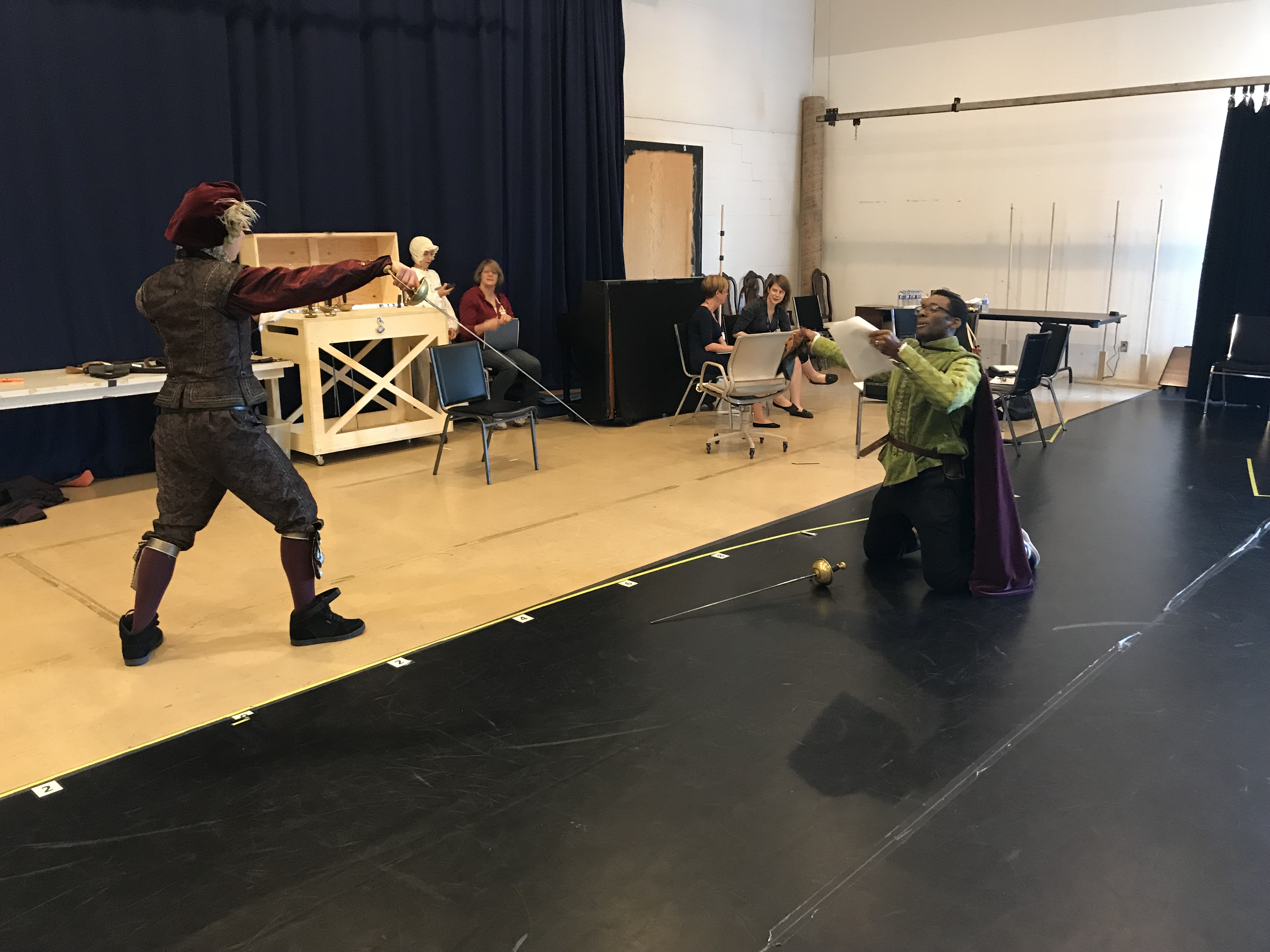

In The Lieutenant Nun, for instance, Guzman repeatedly refuses to trade man’s apparel with a dress; there was consequently something powerful in seeing a refusal to let the body be defined only by clothing, and Guzman’s flying dresses marked one (very funny) instance of self-identity. Groups at this stage took to running their scene silently—with actions but no words. The tussle of movement between Guzman and Sebastian, who was attempting to persuade Guzman into a dress, resembled something of the swordplay or duelling explored in Day 1; a series of parallel lines, stares, thrusts, and retractions. Running silently also pointed to how powerful gesture, presence, and stance can be beyond the words of the text: something particularly crucial with the servant character in The Lieutenant Nun, who has little to say but is a significant presence in the scene: carrying, as the text explains, the dresses designed for Guzman but also going beyond in moments of physical comedy and intervention to frame and choreograph the scene.

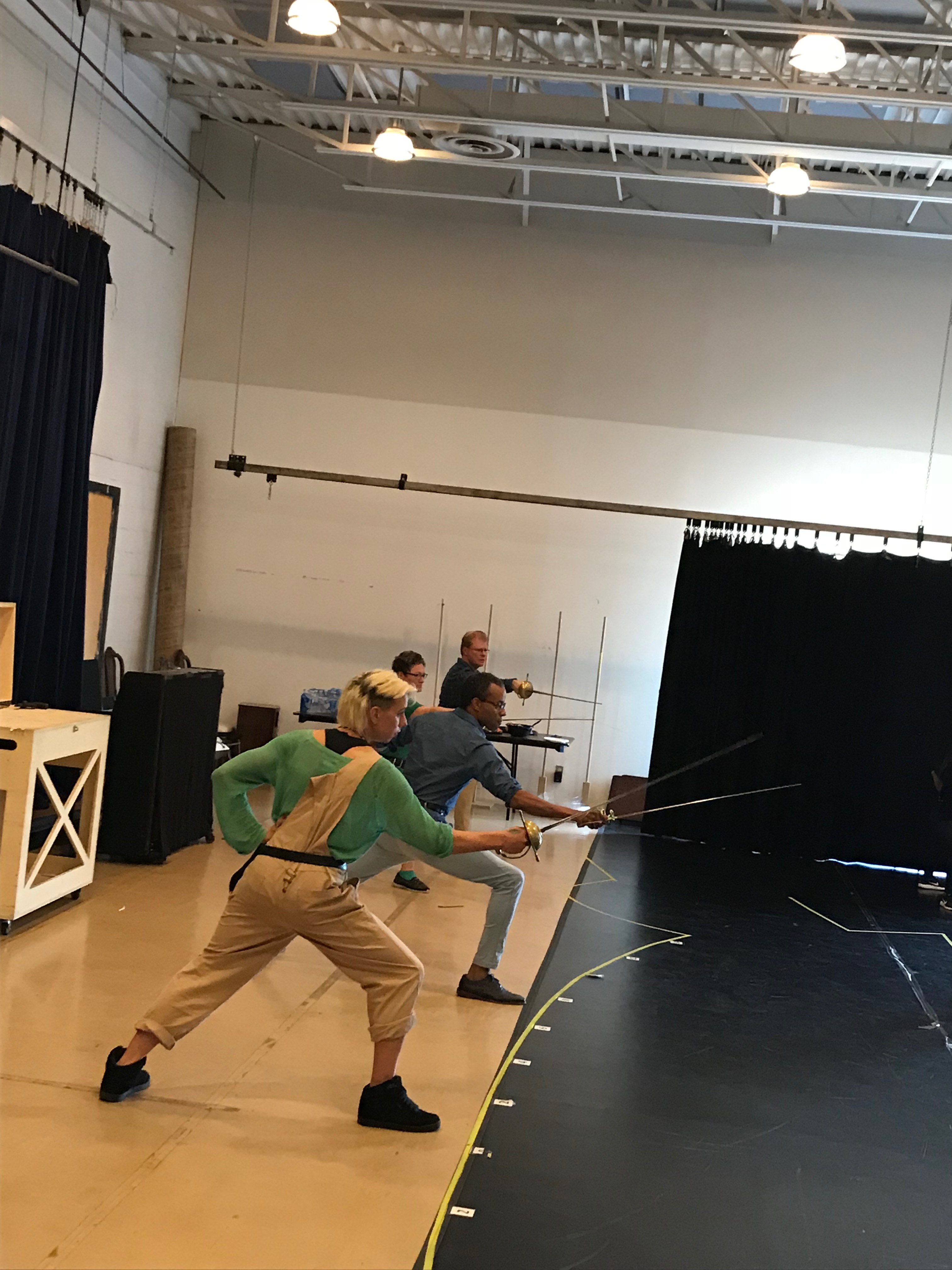

The group working with The Roaring Girl played with the complexity and fluidity of the relationship between gender and costume. Moll shifts between man, woman, and other gendered and non-gendered possibilities throughout the play. Might this allow for a range of subjectivities and a variety of embodied experiences? The group remarked how Emma, playing Moll, went through three different gaits in almost as many lines, in the process of removing and replacing a hat, shedding a cloak, drawing a sword.

In turn, the group played with the possibilities of playing gendered clothing “badly” or, perhaps more accurately, against decorum.

The cowardly Laxton (trembling in fear of Moll) could pull his sword’s sheath up over his waist (think Simon Cowell trousers) and struggle to draw his sword (doing so only on a tiptoe stretch) and to sheath it (cue fumbling and puzzlement).

Do you immediately adopt what you’re wearing, or are you fighting it?

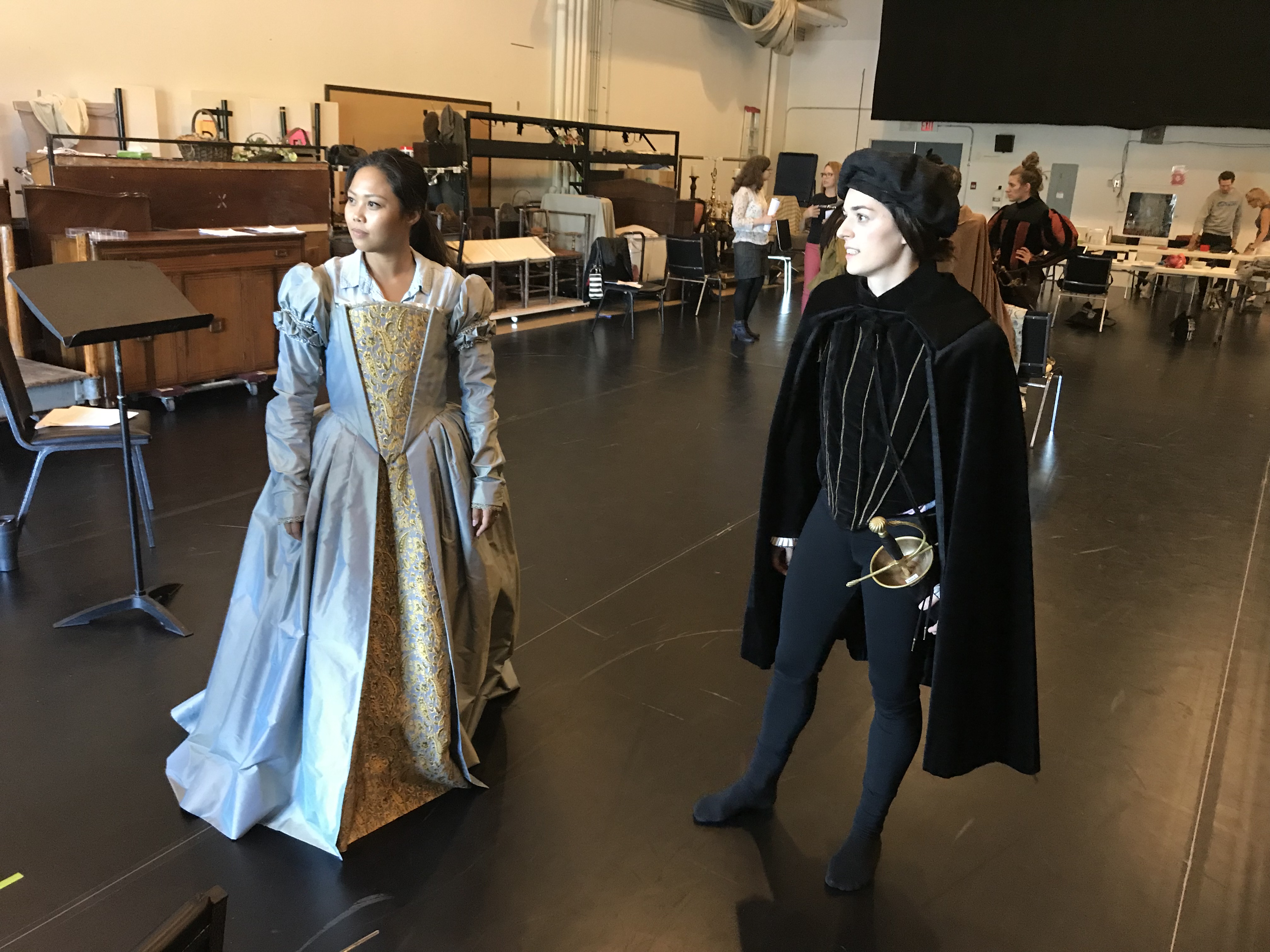

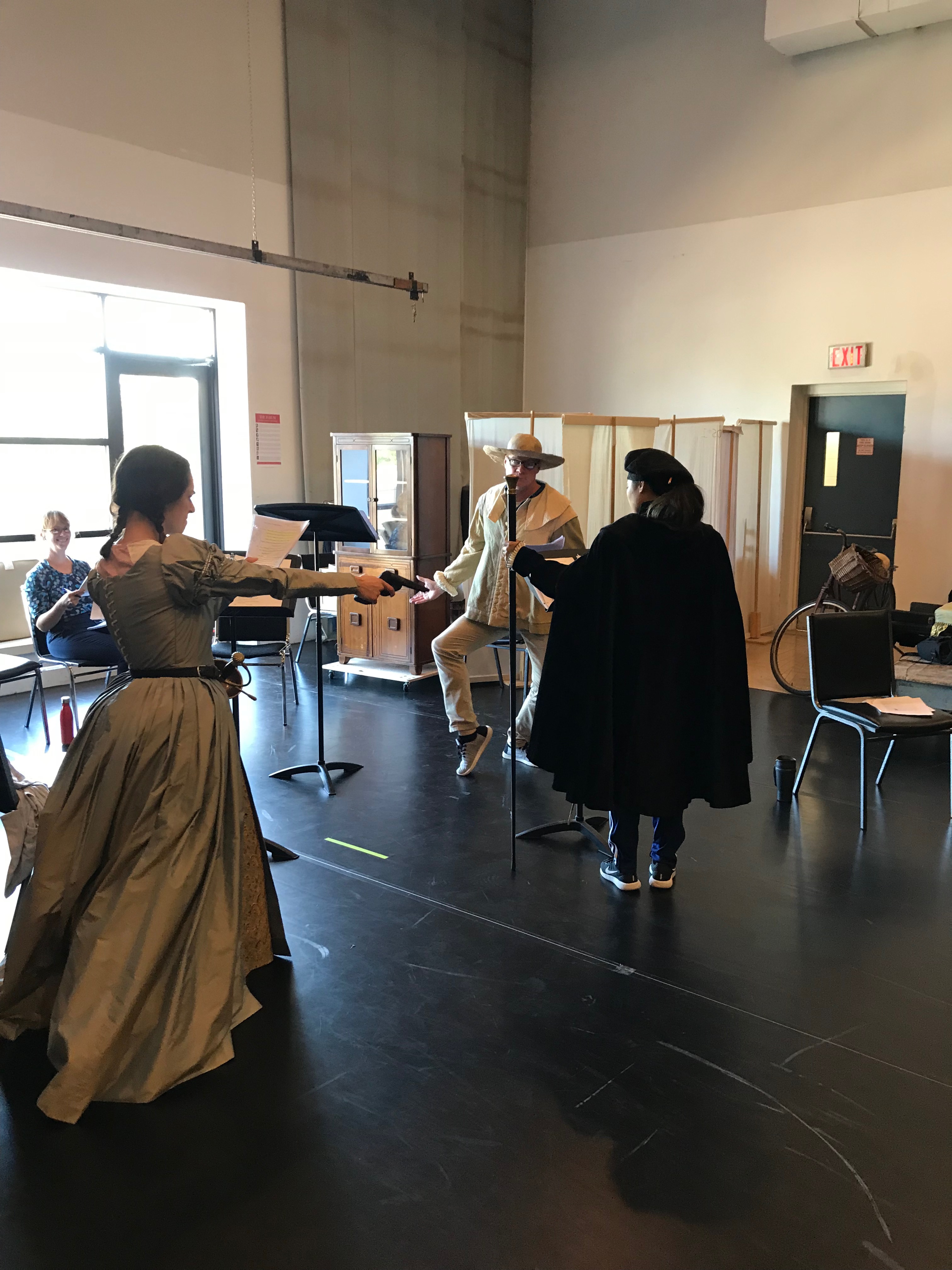

The group exploring Love’s Cure were also playing with these questions of clothing, convention, and pistol-and-rapier etiquette. In this play, the female-born character of Clara was raised as a man and grew up as Lucio—even fighting in wars against the Dutch; her brother—the real Lucio—was raised at home as a girl by his mother. In the scene explored in the workshops, the siblings are back at home together and under pressure to conform to social convention regarding birth sex and presentation. The group experimented with what it might be like for Clara to perform martial acts in a dress.

They also experimented with swapping clothes: putting Clara in the man’s clothes and Lucio in the woman’s clothes, and vice versa, to experience the effect of switching apparel and to gauge how donning new or foreign clothes might affect one’s presence in the room and the scene. These questions also speak to some of the discussions going on in the morning about how “agency” might not necessarily be forms of aggression but, as Ellen Welch observed, could inhere in self-comportment, -composure, decorum. As Clare McManus notes, there are multiple decorums for bodies in early modern performance, and plays encode different forms of skill and performance that require different bodily comportments. Can we discover that multiplicity—and with it that agency—in contemporary performance?

Actors observed the different levels of comfort and discomfort attendant on these switches, and in particular how wearing these clothes accords with experiences in their personal life of particular ways of dressing: for instance, it might feel more familiar to be in a larger dress, but feel more empowering and enabling to be wearing doublet with a sword. Equally, for Clara, the dress and its hidden pistol and swordholder shows how feats of athleticism and martial prowess transcend ostensibly gendered costume.

Liz Cruz Petersen and Pam Allen Brown pointed to how these moments of performance chimed with other developments in the workshop and in the research underpinning it. The instances variously discussed above where characters can dominate a scene through body language alone point to agency beyond verbal performance. Equally, agency inheres in moments where verbal sparring like that between Sebastian and Guzman about correct clothing etiquette can move into physical exchanges mirroring duelling.

You’ve gotta make the scene sing.

Moll, too, along with the cocky servant Trapdoor, are able to move between audience address and repartee with each other: physically and verbally. In these scenes, characters resemble early modern entertainers, able to command respect and attention and generate humour and in turn channel some of the authority of their performing forebears in early modern Europe.

Might we see in these moments contemporary analogues of that broader picture of performance history so well mapped out, for instance, by Clare McManus in her work for the conference on professional female tumblers working in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England? Are these instances where both verbal and nonverbal physical performance (and its interaction with costume) offer a wider and more empowering complement of skills for actors looking to embody classical characters?