To book, please click here.

Before Shakespeare and Engendering the Stage are delighted to announce our next performance workshop, focusing on combat as entertainment—in both Shakespeare’s time and today. Combat, acrobatics and feats of strength were everywhere in the early modern period: wrestling happened on the streets, in the countryside and in plays such as As You Like It, and the most famous male Tudor, Henry VIII, was also a renowned wrestler. Women and men performed strength, sword and rope displays for public audiences. Animal combat was probably an even more popular cultural pursuit than theatre and was watched by all sectors of society across the country and in specially-designed venues in London that were in direct competition with the playhouses. Although modern culture tends to sharply distinguish between theatre and combat as forms of entertainment, the playhouses of Shakespeare’s time were dedicated spaces for play and games of all kinds, and were as much fencing venues as theatres. Likewise, up until the twentieth century music halls and theatres also hosted boxing and wrestling matches, and employed boxers and wrestlers for sparring exhibitions or as actors in plays.

These historical matters have parallels with the contemporary UK wrestling scene. The history of theatre is one of deliberately broken traditions because the London playhouses were closed down in 1642, and boxing and wrestling venues have similarly been controversial spaces subject to control and suppression. In the late-nineteenth century legal changes sent some form of public combat underground, men’s wrestling was banned in London in the 1930s, women’s wrestling in London in the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, and the decision to stop broadcasting wrestling on television in 1985 drastically affected its audience and popularity. But now the UK wrestling scene is so thriving and exciting that a current research project is actually called Wrestling Resurgence. Just as the work of our two projects has stressed the role of women and marginalised people in early modern performance, including combat and strength displays, so contemporary wrestling is thinking anew about gender, sexuality, race and disability in the ring and in its audiences.

Our hope is to use this event to bring these various ideas together, with a focus on using practice and performance as much as conversation to tease them out. Though we’ve swapped staff, methods, ideas and findings before, this will be the first time that Engendering the Stage and Before Shakespeare are in a room together testing out our ideas in performance. We will bring together combat and theatre historians, fight directors, professional wrestlers, sports scholars and animal archaeologist for a conversation in which no one person is an expert, and look forward to generating new conversations and discoveries between our speakers and our audience. For anyone interested in street performance, popular play, combat as a form of entertainment or the links between theatre, circus and sport, we’d be excited to have you join us.

Confirmed participants:

Sarah Elizabeth Cox (@spookyjulie / @wrestling1880s) is the press officer for Goldsmiths, University of London by day, a postgraduate history student by night, and a trainee pro-wrestler with the London School of Lucha Libre during the hours in-between. Through her research project Grappling With History she is piecing together the biographies of long-forgotten British and Caribbean boxers and wrestlers based in east and south east London in the 1880s and ’90s, focusing on ‘The Most Popular Man in New Cross’, heavyweight champion Jack Wannop. Images of Sarah, Hezekiah Moscow and late nineteenth-century grappling are below.

Broderick Chow is Reader and Deputy Director of Learning and Teaching at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, University of London. His research examines the intersections of theatre, performance, sport, and physical culture, and he has published widely on contemporary and historical wrestling, bodybuilding, weightlifting, and strongmen. He is a competitive weightlifter and coach.

Oisin Delaney started training in Knucklelocks School of Wrestling in 2016 under Darrell Allen and Eddie Dennis. He is part of a tag team called The NIC with Charlie Carter and has wrestled for promotions such as Progress, Revolution Pro, Battle Pro, Pro Wrestling Soul and a host of others. The NIC are known for their classic, brawling style.

Hannah O’Regan is an archaeologist with expertise in skeletons. She’s been examining the role of bears in human society, and has become intrigued by the relative lack of research interest in early modern animal baiting and combat – a crucial part of entertainment at the time. She’ll be bringing Bernard the bear with her.

Katrina Marchant is a material and cultural historian, sword fancier and lover of pugilism. She has an extensive performance background in musical theatre, theatre, compering, improvised and stand-up comedy, works as a costumed historical interpreter and educator at various heritage sites and wrote a PhD on trash, trifles and Protestant identity in the early modern period.

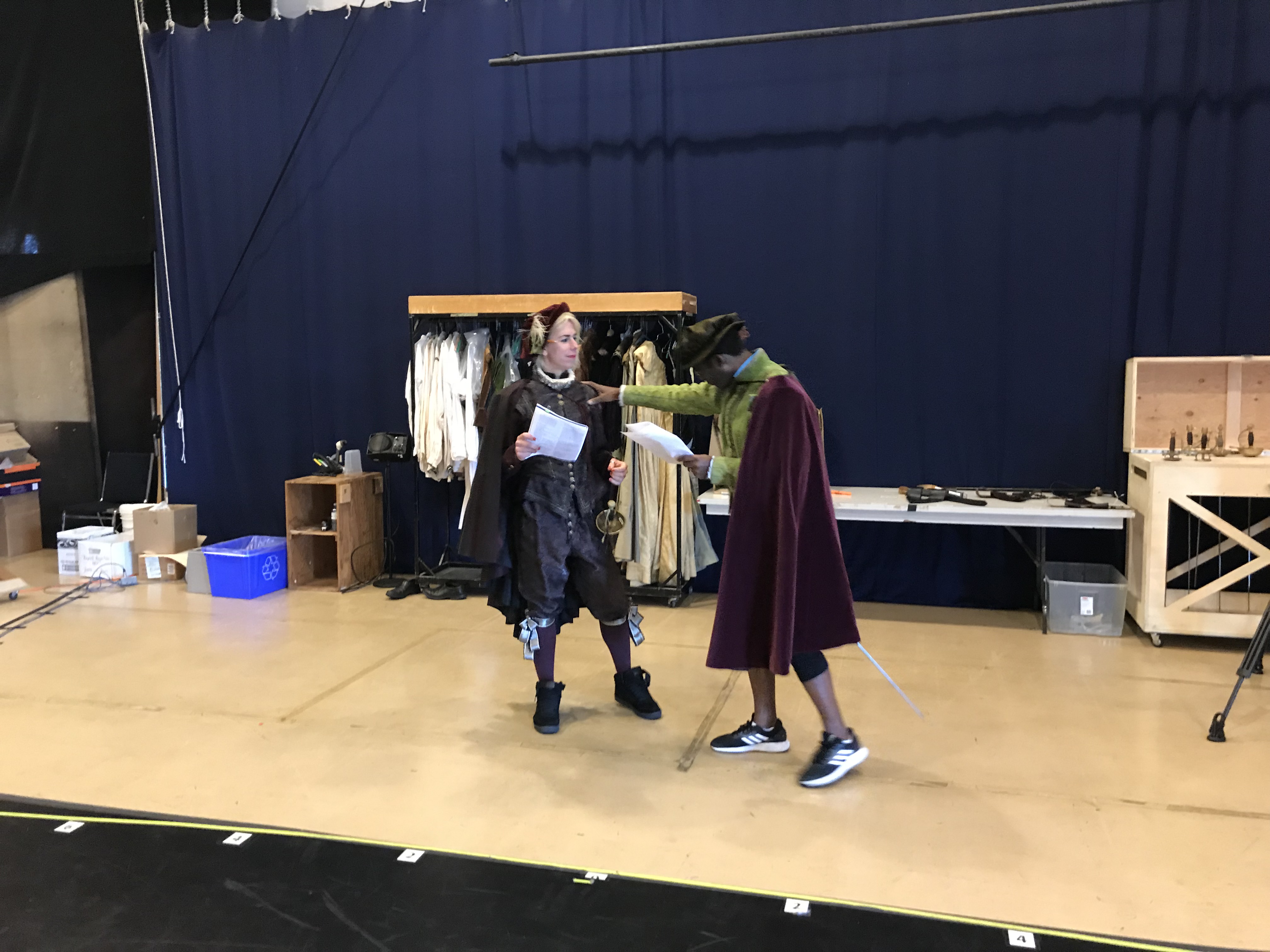

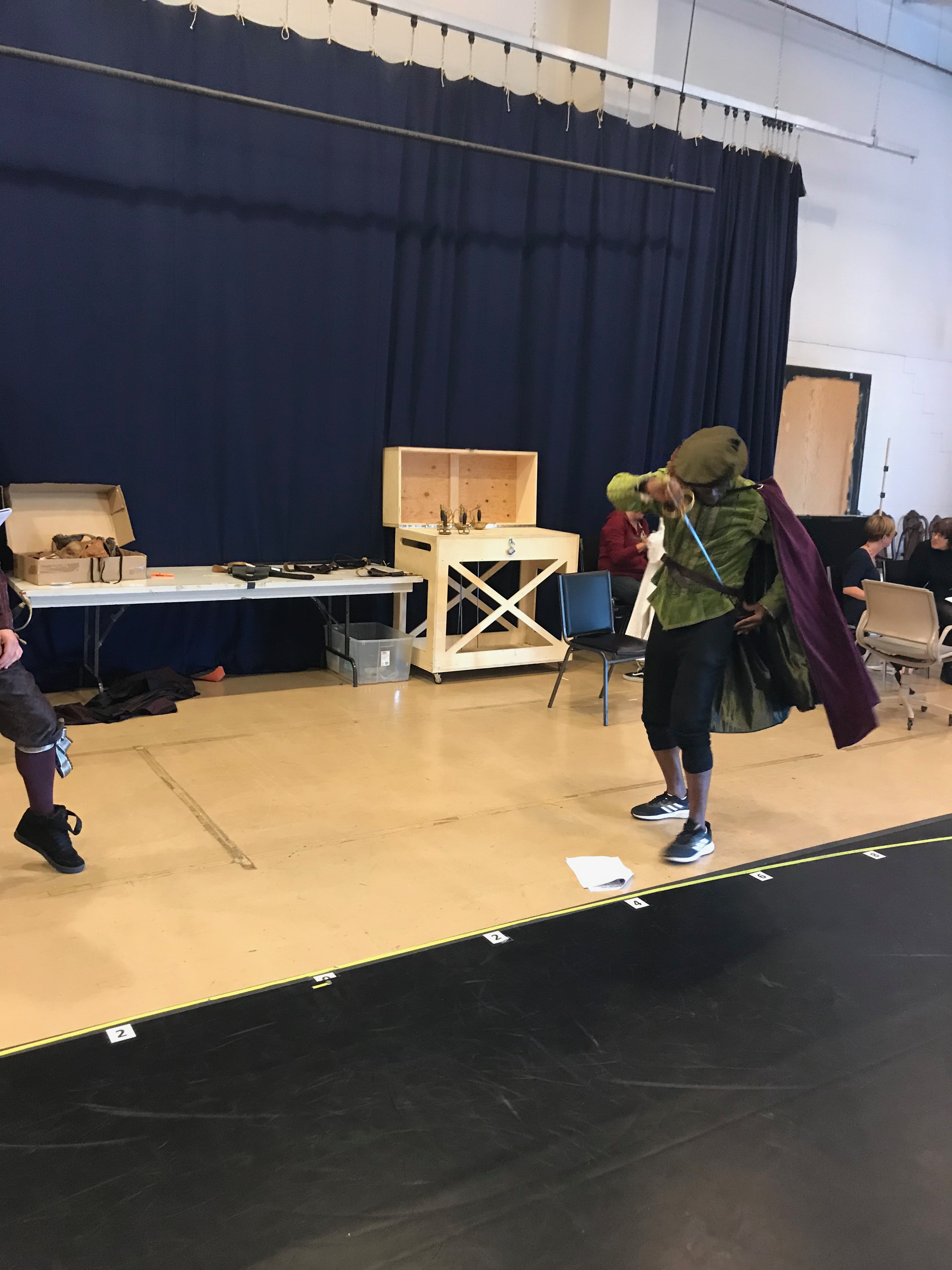

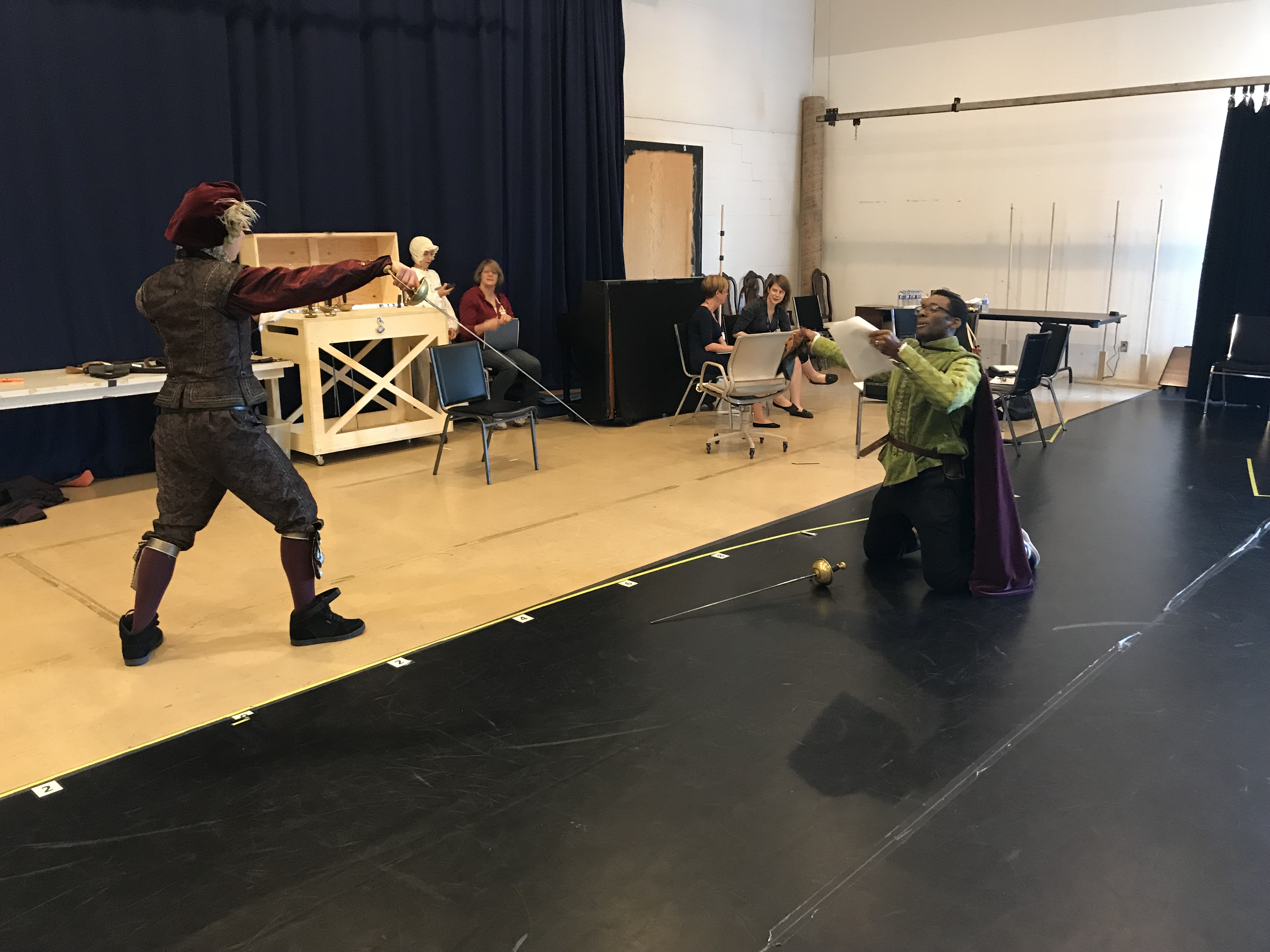

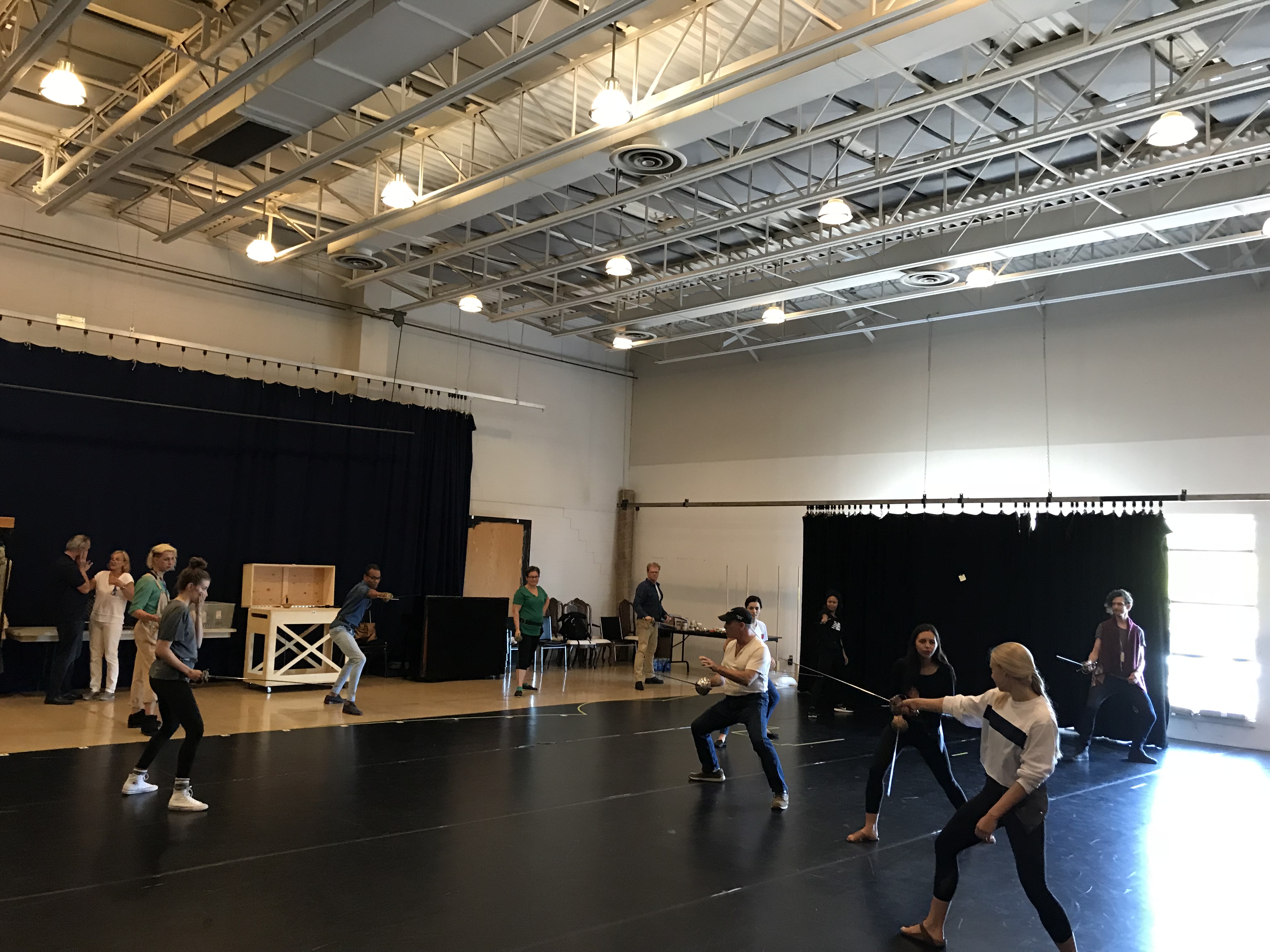

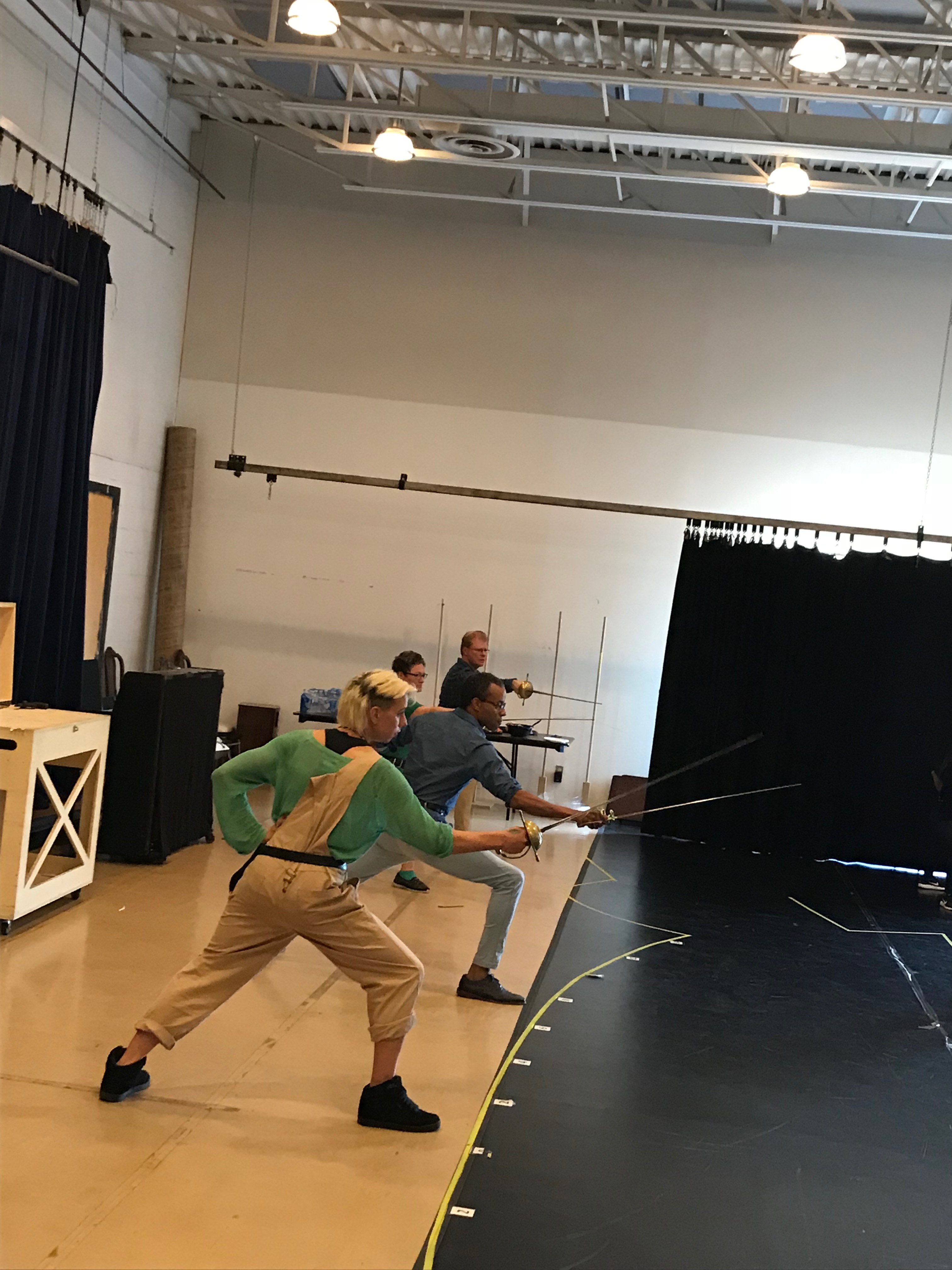

Duellorum are Craig Hamblyn and Kiel O’Shea – fight directors, stage combat teachers, and martial arts historians, combining academic research and practical experimentation. They specialise in the adaptation of historic martial arts for performance and spend a great deal of time very carefully and thoughtfully hitting one another.

Location and accessibility

For a map to the theatre, see here. For full Access information, see here. The map below highlights the easier way to get to the George Wood Theatre via step-free doors to the building and theatre, as well as step-free access to two gender-neutral toilets (room 165), one of which is fully accessible.