During our week last September working at the Stratford Festival Laboratory with academics, actors, theatremakers, editors, and directors, we had plenty of opportunity to reflect on the nature of practice-as-research, or performance-as-research, as a mode of scholarly enquiry [see our blog summaries here]. We also had the chance to contemplate what it means to bring experts not only from different disciplines but also from different practices into the same room. Through the course of the week, we spoke with many of the participants about this experience. The excerpted observations, insights, and snippets of this post are drawn from transcribed interviews about bringing scholarship and professional performance together. In short, we’re asking: What’s it like having a more balanced room of academics and actors, in the context of a process with no final product to work towards? Please feel free to keep the conversation going in the comments… The next post will build on the comments here, sharing participants’ thoughts on ways forward— possible futures for this form of work, its methodologies and discoveries, in teaching, in theatre practice, and in scholarship.

***

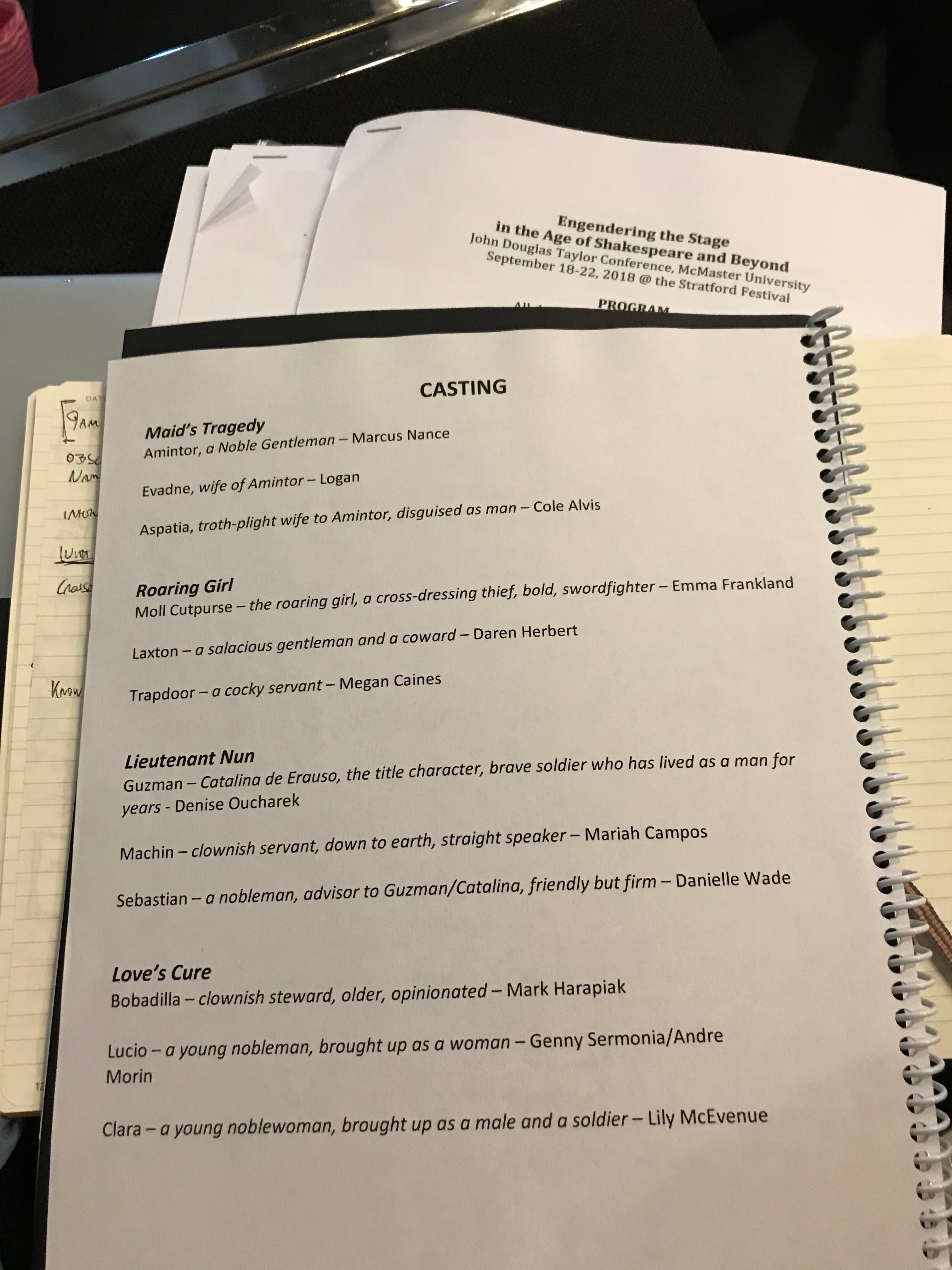

EDWARD “MAC” TEST. I knew that we were going to be able to work with actors and see them actually perform a translation that I’ve written—a translation of a play [La monja alférez, or The Lieutenant Nun]. […] But that said, it was exciting and unnerving for me to come here and do this kind of work, because I’ve never done it before. I’m not a playwright—it’s the first time I’ve done that. So I came in anxious, nervous, and excited—all of those emotions swirling together. There’s something with scholarship—and of course with theatre—we tend to stick to the text; and while we enjoy going to performances, we don’t usually writethe play, which is what I’ve done; we don’t usually direct anything—and I’ve watched that happen and interacted as a sort-of-director, so that’s all new to me. And it’s going to inform the way I do my scholarship, the way I look at the play, and the language—I’m going to be thinking forever of these actors saying those words and moving around and the deliberations around what appears on a stage. It’s all been very magical.

COLE ALVIS. Having academics in the room is new. I’ve come through Stratford to do the Indigenous Directors Lab on two occasions, so a “laboratory” setting that’s outside of—or perhaps in relation to—the season, but distinct and specifically about exploration… and that’s a real gift to get to be part of this, because my practice tends to be in new work—or new-er work—where it’s easier to place myself and my communities at the centre of that experience. You don’t often see Indigenous and culturally diverse leadership within the Stratford Festival, but in these Labs, there’s opportunity for that. And then to see how the classical form can shift, when there isn’t the parameters of bums in seats and all of the expectations of what the “Stratford Festival” generally does. To me, these Labs are forward looking—about where Stratford might be able to go, to include worldviews and lived experiences of the people that make up… this place.

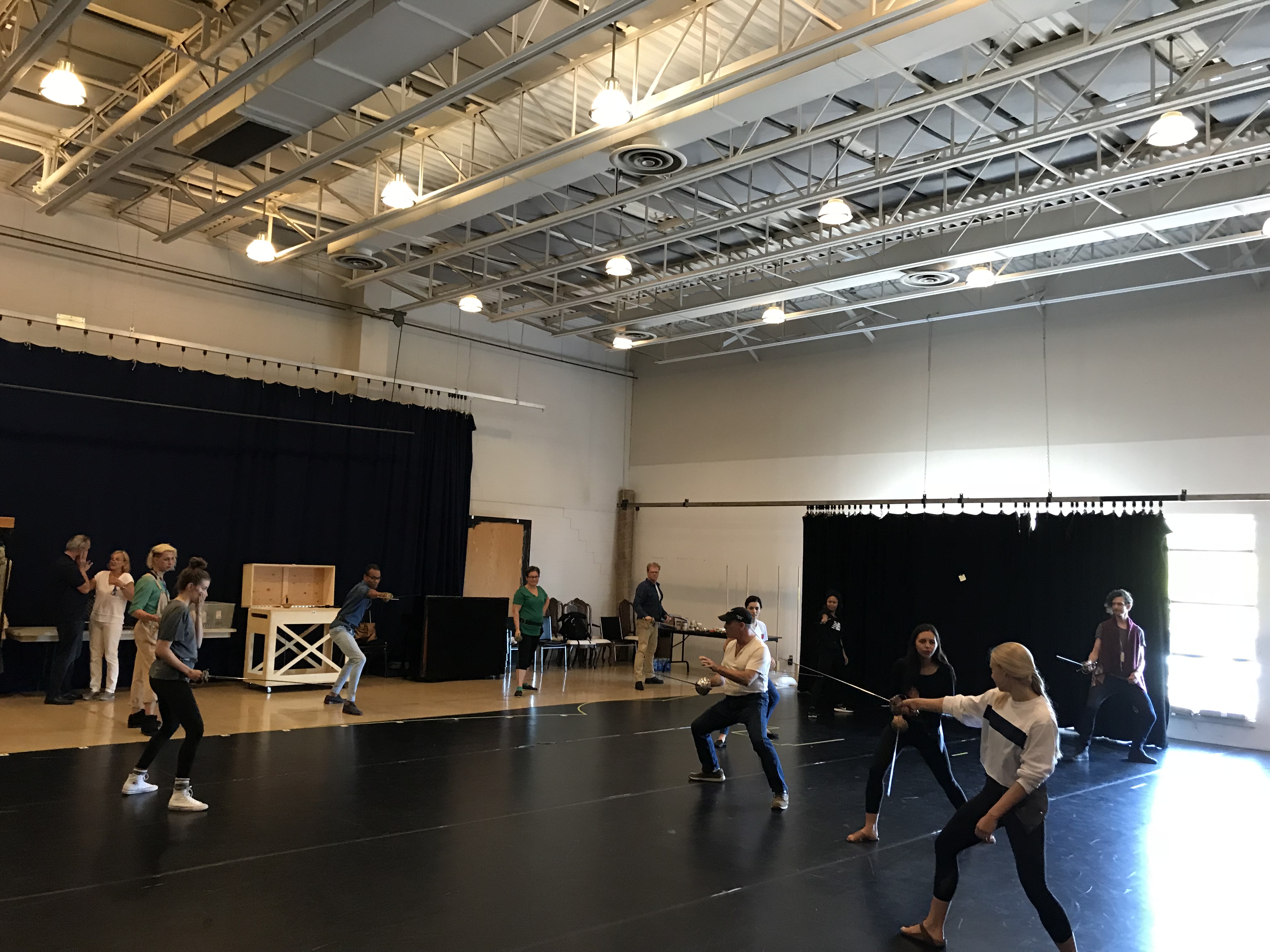

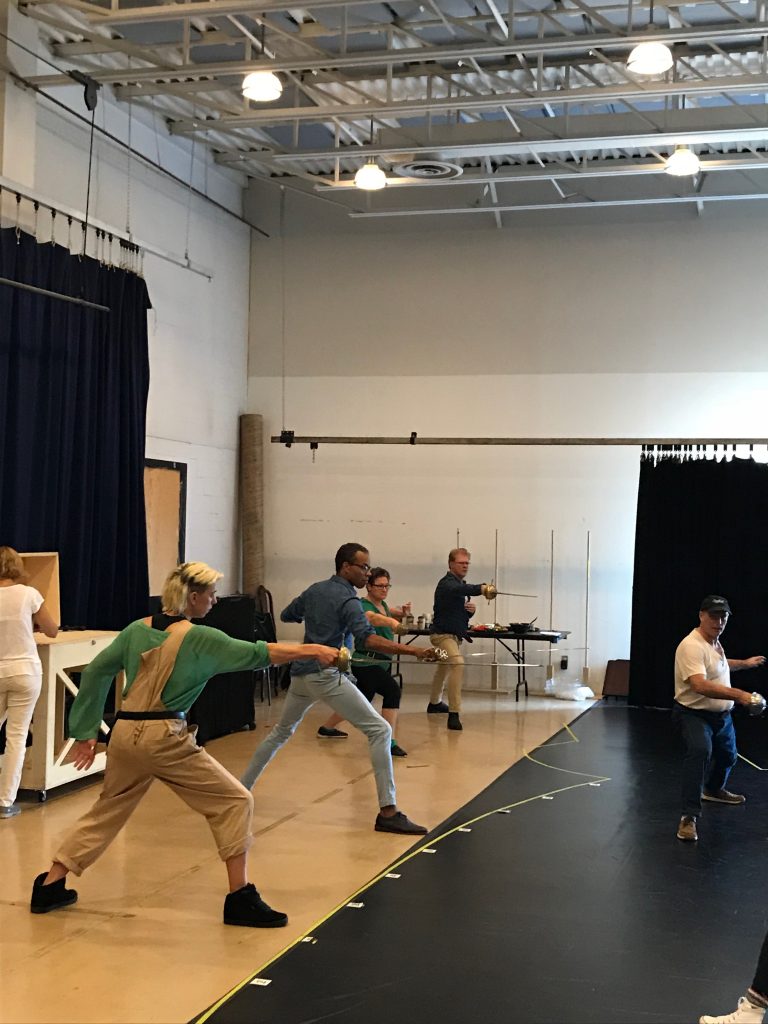

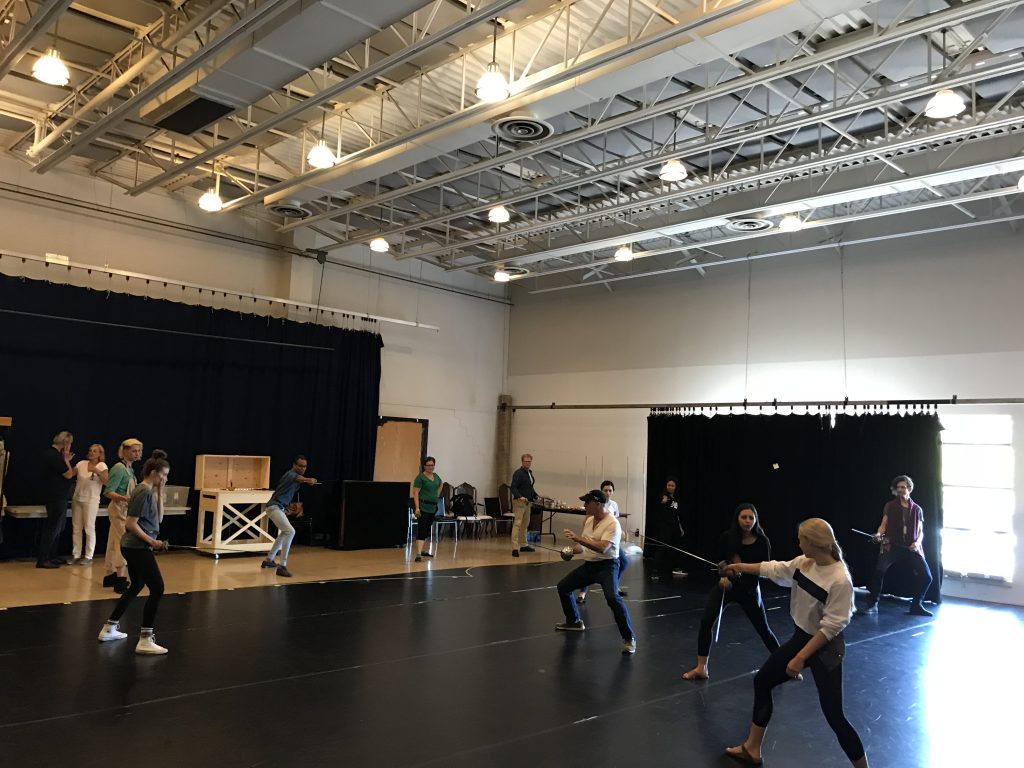

ELIZABETH CRUZ-PETERSEN: I loved working with professional actors and the entire process of making scenes come to life. I came to this workshop with the hope of gaining a better understanding of the difficulty (or not) of staging swordplay scenes and the unique attributes women contribute in the swordfights and dances. However, I wonder, how much the actors understood our goals as scholars in this process. And we of theirs? At times, it felt as if this workshop was for our benefit only. The actors were like tools for us (“I’d like to see you do this” and “can that happen”). Even when I asked, “what do you think of this?” I wonder if they were thinking… “Well, what do you want me to think of this?” What stake did they have in this process? Keira [Loughran] or was it Emma [Frankland] mentioned that there was no production—there’s no end, there’s no investment in it; which makes sense to ask what is the actor’s investment in this? Did they find our contribution useful in enhancing their skills as actors?

ERIN JULIAN. PaR is supposed to be bringing people with different backgrounds and training together, as we both know a lot about this broad subject of theatre, and we both have things we can learn from each other, and we should be training knowledge. And we are embarked on the same project, though […] we don’t have the same language to talk about it yet. I would love to see that division be bridged, as I feel like through this process and through the work I’ve also been doing here [at the Stratford Festival, shadowing Comedy of Errors] it’s changed my whole way of thinking about theatre and what we’re doing, what we’re studying… A question came up this morning—a very heated question—about “why are we doing this? why are we trying to excavate these plays, what are we looking for—are we trying to redeem them?”—and I think these conversations around how our history and the present and future speaking to each other […] is work I have seen here and seen through other work we’ve been doing with Keira [Loughran]…

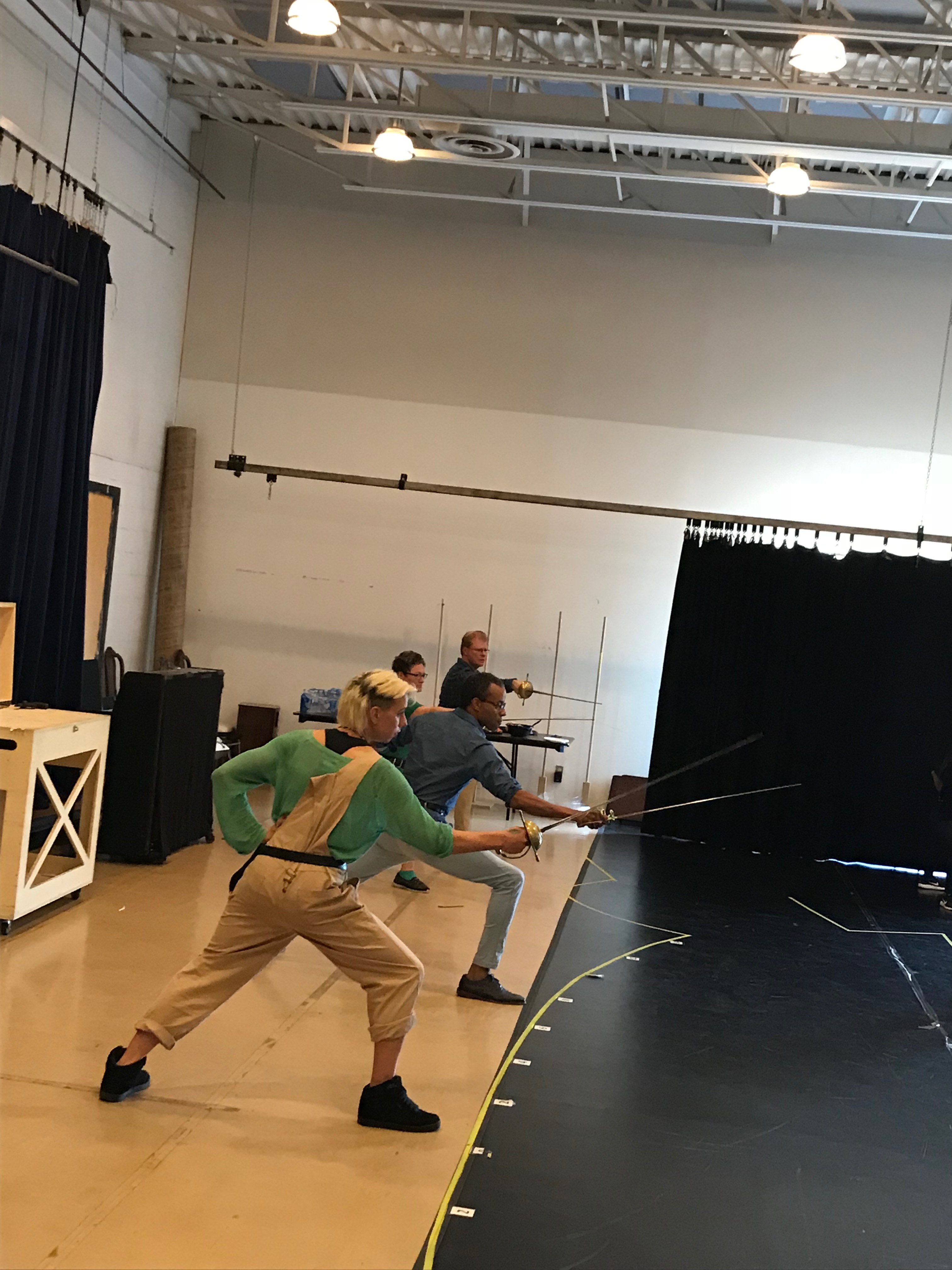

PAMELA ALLEN BROWN. I was really glad to see the actors with the professional fight captain [Wayne Best], with the way he taught them; it was really fulfilling for me (because I talk about skill so much in my [forthcoming] book) to see his skill and presence and showing by doing—and he really knew how to teach… As he did it, you can imagine how skills might be transferred, and sense […] the effect on the actors. What I noticed is they imitated so much better than mere mortals like me, starting with putting on the sword. Because I assumed wrongly (because I’m not in that world) that if you were doing Shakespeare at all you would know how to wear and use a sword, but they don’t, actually, because a lot of people—particularly women but also men—have never used one or had a role where it depends on one… A lot of people had never put one on. So as they’re total newbies to it, and they’re acquiring this skill slowly and following along, it was wonderful to see the awakening stirred by this weapon [. . .]. This power—which is phallic power, a masculine symbol of power—was taken on by the women and the men too, and each one individually yet with gendered inflections which were not predictable, so that it upsets our whole idea of what’s masculine and what’s feminine—that whole exercise taught me more than tons of words… [Wayne Best] was, to me, so fascinating to watch, when I would move from looking at him to somebody else, they were trying to strike their own sort of control and give some sense of “I know exactly how to use this sword,” and that seemed close to what the divas [of the commedia dell’arte] would do – they’d start off with a few skills acquired as street entertainers or courtesans from low-status families, and in a short time, they could create an entire persona where they coolly use swords, they can wear a mask and be Pantalone, or they can be a great grand lady, they can be a queen. So this confidence and this sense of coming off as poised and cool[as Wayne put it]… there’s something about the coolness (and everybody knows what that means, but it’s something that you need to get in your body) that’s basic to acting and the readiness it demands. Skill can only go so far, however. Charisma and imagination are rare in anyone, but the actor who has “It” (as Joseph Roach puts it) can do (almost) no wrong. I was talking to Denise [Oucharek; playing Guzman in The Lieutenant Nun] and she was telling me about she’s always trying to go beyond labels, including gender ones; her career has included a solo act in the persona of a famous singer-comedienne, and a wide variety of plays and roles—hearing that, after seeing her work, is a rare experience. When you’re a drama scholar trying to think about the first actresses and their roles, evidence shapes your work but your mental theatre, the people you put on it, affects your choices and arguments… So it’s a thrill when you see Denise starring in the Lieutenant Nun and think without any doubt “you’d be a great Duchess of Malfi,” or “I’d love to see your Roaring Girl,” […] because her determined disruption of gender and her embodiment of masculine virtú are so diva-like and so unlike most interpreters who take on these roles today.

CLARE MCMANUS: I’ve been looking to work in a different way and bring different skills to this training and kinds of expertise in collaboration. Certainly working with Emma Frankland on The Roaring Girl, and watching the other actors respond to what Emma has been suggesting, has been really exciting, in terms of thinking about the complexity of present-day casting. That’s the thing that is really coming up. And one of the really pressing things today was what the use of history is and the use of pastness and our relationship to it. And that seems to be something that’s really pointedly at issue with PaR. And I think in ways that can be dodged a little bit in other disciplines, but you can’t dodge it when you’re dealing with embodied performance and embodied voices—and voices and bodies that want to resist what’s written in the text. So there’ve been some quite uncomfortable moments, and moments where it feels a little bit like you’re asking the actor to sacrifice something, to say something that is unpalatable to them, and then the reality of their experience brings home how terrible the text is, in some ways. But that sounds more pessimistic than it actually is. I feel more optimistic about this, because I feel like one of the things, just one of the things that’s starting to happen, is this sense of drawing lines and drawing points of resistance against texts where they need to be resisted, where they need to be spoken back to.

LUCY MUNRO: For this workshop, the casting is really, really interesting, and really stimulating for me all sorts of questions, because we have an adult man [Marcus Nance] playing Amintor [in The Maid’s Tragedy], we have a 14-year-old boy playing Evadne [Logan Brideau], and then the actor playing Aspatia [Cole Alvis], who is nonbinary and whose pronouns are “they,” and Cole […] has been incredibly interesting and articulate on that question of what is Aspatia’s gender identity. And so yesterday when we were working with them on the scene, we were actually referring to Aspatia as “they”—and trying to think about what does it mean if Aspatia is a nonbinary characteras well as being played by somebody who uses “they.” So that was really interesting. But the casting of Logan, a 14-year-old boy, as Evadne also does really interesting and strange things with the scene, because it becomes about age as well as being about gender. And one of the things that we talked about is that the fact that the in the play, Aspatia and Amintor were betrothed (which can be as binding as an actual marriage) and then that was derailed by the King insisting that Amintor marry his mistress Evadne. So you have this arranged marriage between Amintor and Evadne. [. . .] And there’s all sorts of interesting power dynamics [. . .] when Evadne comes on (unfortunately we don’t have any stage blood) but comes on with a knife in a white night gown, and says “joy to Amintor, for the King is dead” …

ROBERTA BARKER: Something that’s really interesting for me being involved with this project is that I’ve done quite a bit of performance-as-research before but it’s been almost completely—well in this situation of actors and academics working together—it’s been almost completely working on nineteenth-century theatre. And that’s so deeply different because we have so much. You know if you start out in seventeenth-century theatre and then you go into nineteenth-century theatre it seems like this incredible bonanza of visual images, stage directions, reviews, comments—like you literally know what actors originally did—like where they dropped their hat. So you’re able to say, “Show me exactly what it looks like if you do it how the reviewer describes this whole scene,” which we don’t have for early modern plays. A huge interest that I’ve always had as far back as beginning to write about the relationship between early modern drama and contemporary performers is this sense that for contemporary performers, especially in terms of gender, performing early modern plays is very complicated and in many cases very uncomfortable. And in some ways there can be a lot of productivity and meaning in embracing the discomfort and exploring the discomfort and seeing what comes out of it. And I think that’s one of the things that’s been really powerful for me, in being in the room and working with the actors, and also with the discussions—is that sense of, as Lucy was just talking about, the complications, the discomforts, the questions, and also these huge possibilities that come in when you bring a body, you bring a lived experience into a role. That’s very different from these early performers that Lucy and I are interested in (discussing the boys who first played roles like Aspatia and Evadne). Their lives, their training, their assumptions, and how they even worked on the roles are so radically different from what we’re doing in this room.

ELLEN WELCH. I didn’t quite know what to expect, and I guess if I had assumptions, it that there was going to be a lot of detailed work with scenes; so I guess what surprised me was the amount of talking and sharing and meta-level discussions that have gone on. And all that is really useful, and it’s made me think about the process of being a researcher in a different way to the way I expected to interrogate my own process and experience…

NATASHA KORDA. I think this [Lab] has been really focussed on process, in a way that has been transformative for me. I am going to bring away from this experience techniques and exercises, and different ways of thinking about teaching, research, and many other things—including how we present our research. I think we’ve been given a lot of tools, and maybe a way to go forward into the future with them would be to try to have a conversation about, what do we academics do with those tools now? How do we really use them in a way that will lead to something new, such as different forms of knowledge production?