This is the second of a series of posts that set out Engendering the Stage’s research into the roles of women in the economic structures that surrounded the early modern stage. They derive from our documentary research project, ‘Engendering the Stage: The Records of Early Modern Performance’, funded by a Research Project Grant from the Leverhulme Trust.

As part of our work in the archives, Lucy Munro and Clare McManus have been delving into the history of the Fortune playhouse between the 1620s and 1640s. Building on earlier research, we have discovered a remarkable story of women’s investment in this playhouse and have begun to connect it with the history of female performers such as the rope-dancer and tumbler, Cecily Peadle.[1]

In this post we will set out what we have found, tell the stories of some of the women who invested in the playhouse, and consider how their involvement with the theatre relates to the broader history of performance at the Fortune, where plays were staged alongside rope-dancing and other ‘feats of activity’.

Introducing the Fortune

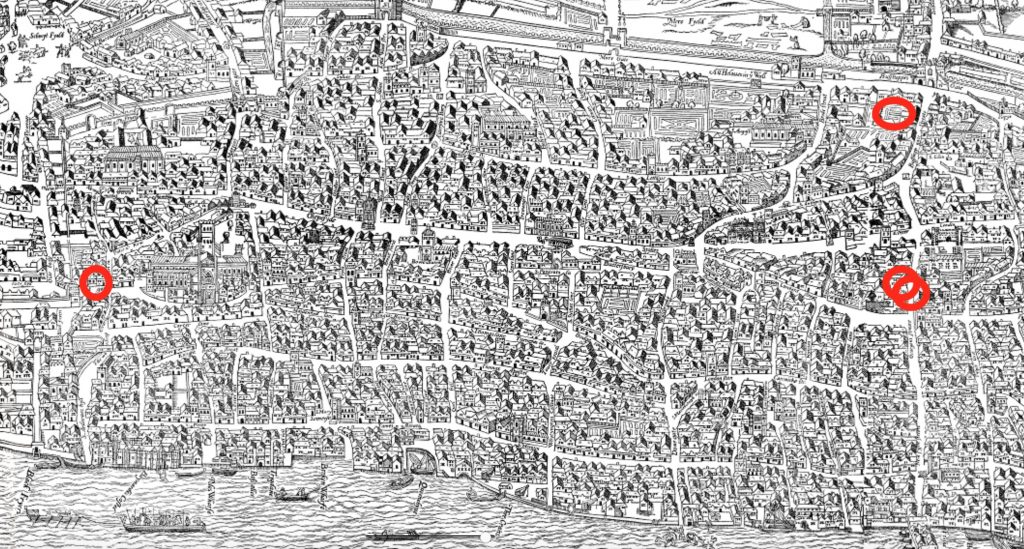

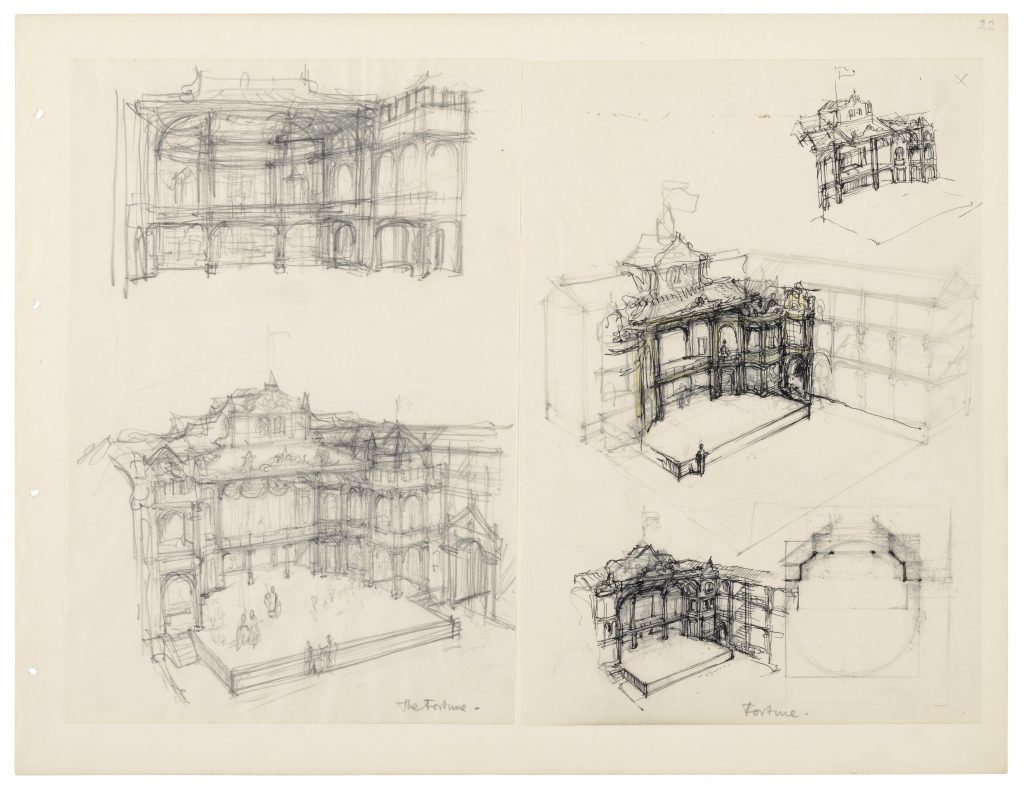

First, a little background. The Fortune playhouse was located between Whitecross Street and Golding Lane (now Golden Lane) in the parish of St Giles Cripplegate, just outside the northern walls of the City of London. It was originally built by Philip Henslowe and Edward Alleyn, the actor husband of Henslowe’s step-daughter, Joan Woodward, in 1600. It followed the pattern of the Globe playhouse, being a timber-framed building open to the elements, but it was square rather than polygonal.

In 1621, the Fortune suffered a catastrophic fire and burned down. In order to finance rebuilding the playhouse – this time in brick – Alleyn created a 12-part lease, issuing full and half shares in the second Fortune to investors who paid up to £83 6s. 8d. for a full share and £41 13s. 4d. for a half share. The National Archive’s Currency Converter suggests that these sums would be worth around £11,000 and £5,500 today, so the leaseholders had to be relatively well-off or have access to loans. Their leases were to last 51 years and they were to pay £10 13s. 10d. or £5 6s. 11d. rent per annum. The lease agreements included a clause stating that the leaseholders should not ‘divide, part, alter, transport, or otherwise convert the … edifices and buildings … to any other use or uses than as a playhouse for recreation of his majesty’s subjects, his heirs and successors’.[2] This clause was to create problems when the London playhouses were closed temporarily during outbreaks of the plague in the 1630s and early 1640s, and then closed indefinitely when the Civil War broke out in 1642.

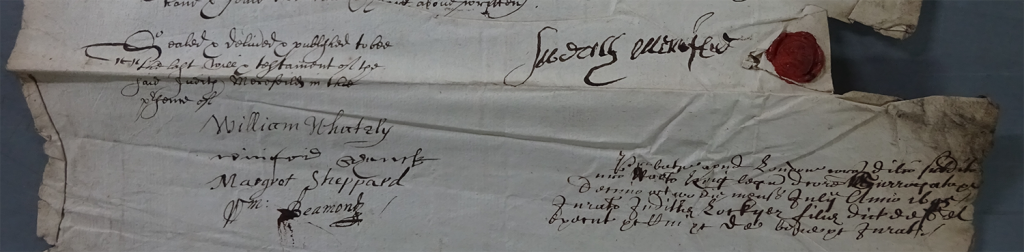

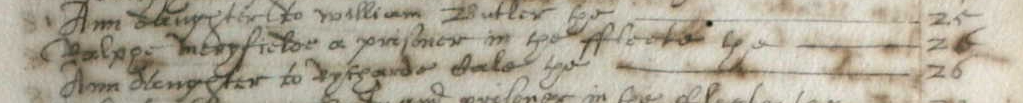

Documentation for early modern playhouse investment rarely survives, but most of the original set of lease documents issued by Alleyn, dating from 1622-4, have been preserved in the archive of Alleyn’s papers at Dulwich College, the charity that he founded in 1619. Some of them can be viewed on the wonderful Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project website, led by the theatre historian Grace Ioppolo, which includes digital photographs of some of the most important documents in the Alleyn archive.

The leases show that early investors in the second Fortune included actors, the carpenter and bricklayer who had worked on the playhouse, two merchant taylors, an innholder, a barber surgeon, a stationer, a glazier and a clothworker. They also included three women, all of them widows: Frances Juby, widow of the actor Edward Juby and an old friend of Alleyn, who acquired her half share on 20 May 1622; Mary Bryan, who acquired her full share on 24 March 1624; and Margaret Gray, who acquired a half share on 1 August 1623, added a full share on 29 January 1624, and then added another half share on 21 April 1624. Gray’s lease can be viewed on the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project. We have also known for some time from other documents at Dulwich that Susan Baskerville – who was the widow of two actors and also had an interest in the Red Bull playhouse – held a share in the Fortune lease. These four women have been researched by other theatre historians, notably Susan Cerasano, who in 1998 published a detailed account of their investments in the Fortune, drawing on the leases and some transcriptions of legal documents that also survive at Dulwich.[3]

New Findings

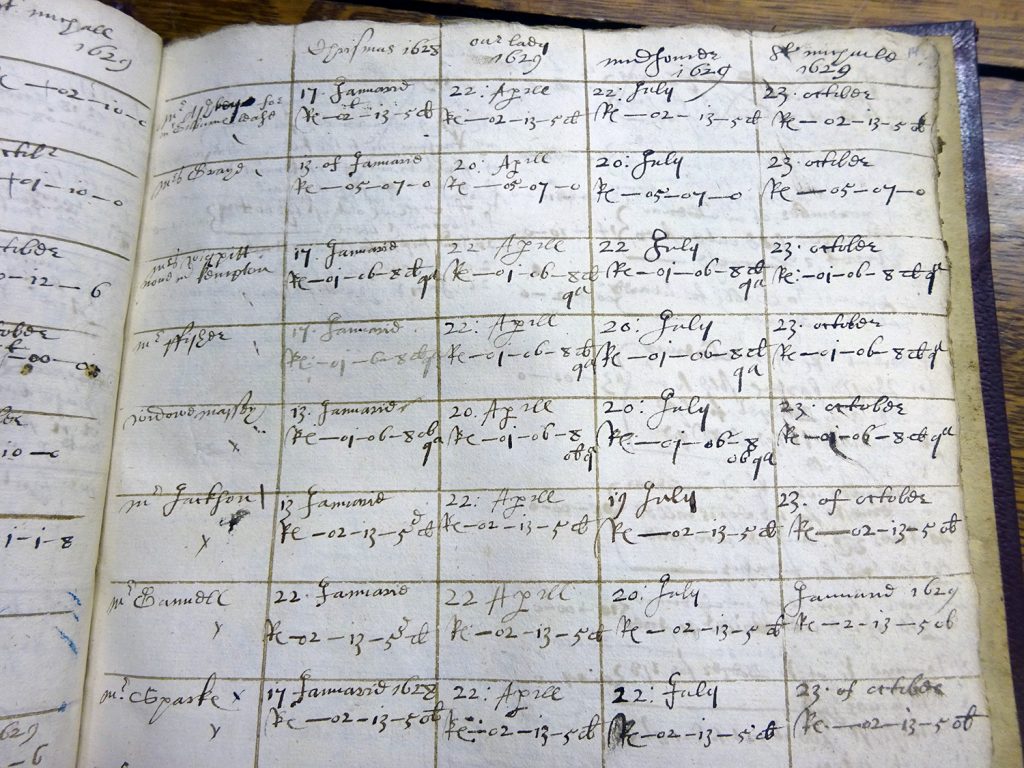

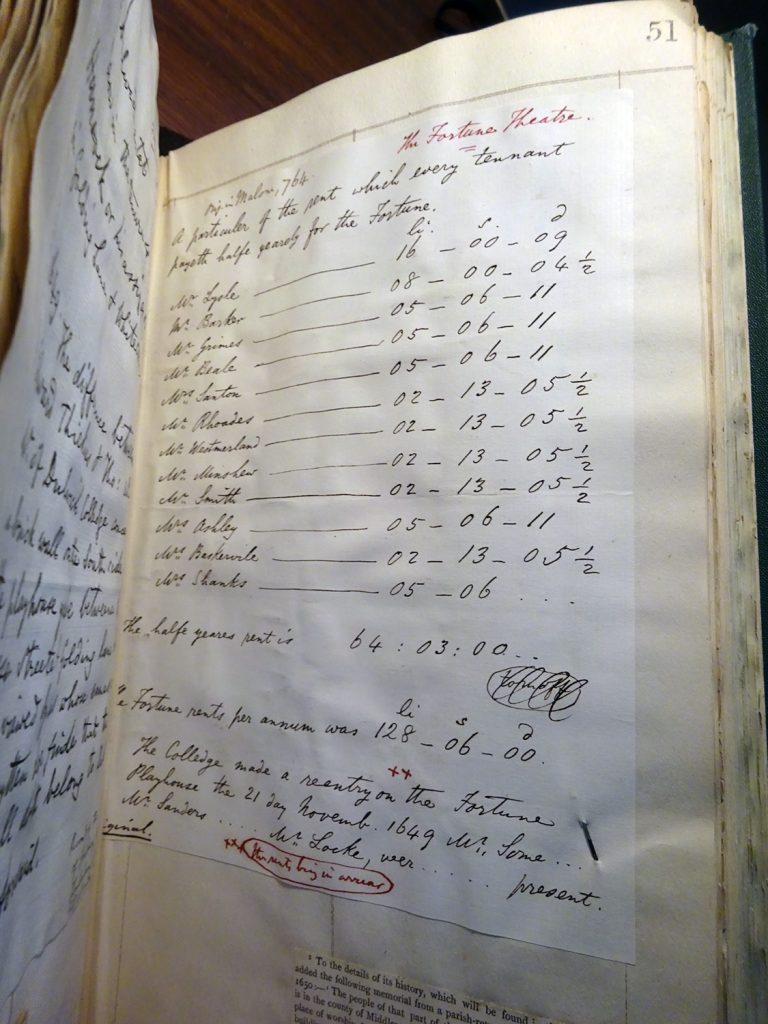

Our new research into overlooked and neglected documents reveals an even more remarkable story. When Alleyn established Dulwich College in 1619, he settled his property, including the Fortune, on the College. After his death in 1626, the playhouse leases were managed by the College, and the leaseholders appear in a set of rent books and account books that are preserved at Dulwich. These fascinating documents detail the payment – or non-payment – of rent by the Fortune leaseholders, quarter by quarter, between 1626 and 1649, when the College evicted the leaseholders for non-payment of their rent during the Civil War. They present the most detailed evidence that has yet been discovered for the finances of a seventeenth-century playhouse, allowing us to track the movement of shares between different individuals when they were sold, transferred or inherited, and to see moments at which leaseholders refused or were unable to pay their rent.

Alongside the account books, we have been reading wills and documents connected with lawsuits that were periodically waged by the leaseholders and the College in the Court of Chancery. Some of these documents survive in the court’s records at The National Archives at Kew; others are preserved at Dulwich, having been prepared for the College’s legal team. Detailing the inside stories of battles over individual shares, they allow us to trace interactions and relationships between the leaseholders and to identify individuals who were never officially recognised as leaseholders by the College but who nonetheless had a claim to the playhouse’s profits.

We did not discover these documents on our own, but with the help of earlier theatre historians. We thought that the Dulwich archive might include documents recording the rents paid for the Fortune leases because in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century Edmond Malone made notes from one of the documents and his notes were transcribed later in the nineteenth century by James Orchard Halliwell Phillipps and pasted into a scrapbook now held by the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC.

Another scholar, John Payne Collier, drew attention to financial accounts at Dulwich in his 1841 book, Memoirs of Edward Alleyn, writing, ‘in Dulwich College account books, kept by Mathias Alleyn, “the widow Massye” is entered as the tenant paying rent for her share of the Fortune’.[4] We were also able to draw on earlier scholarship on Dulwich College and its archive by George F. Warner, William Young and Francis B. Bickley.[5] We had leads to follow up in the Court of Chancery because in the early twentieth century the husband-and-wife team Charles William Wallace and Hulda Berggren Wallace undertook an exhaustive study of these records, leaving notes and transcriptions that are now in the collection of the Huntington Library in San Marino, California.

Drawing on these sources, and with help from Calista Lucy, Keeper of the Archive at Dulwich College, we have pieced together a near-complete history of women’s investment in the Fortune playhouse. We can demonstrate that 24 of the 71 identifiable individuals who claimed an interest in the playhouse between the mid 1620s and late 1640s – either by buying a share, inheriting a share or having a claim to a mortgage on a share – were women. In other words, around one third of the investors in the Fortune were women. Moreover, the number of shares held by women never drops below 2½ shares, out of the total of 12 shares, and in some years it rises to 6 and even 6½ shares, meaning that the majority of shares were in women’s hands.

The Fortune is not the only early modern playhouse in which women had a financial stake. Nonetheless, the way in which a diverse group of women invested in it over an extended period of time is remarkable, as is the amount of detail that we have been able to reconstruct about these women’s lives and the circumstances in which they invested in the theatre.

The Women

Some of the women who invested in the Fortune held shares only briefly, inheriting them from relatives and quickly passing them on. Others held them for extended periods of time. Here is a roughly chronological list of the women whose investments in the Fortune we have traced:

Frances Griffith Juby (c. 1574-1631) (leaseholder 1622-31). Widow of the actor Edward Juby. She leased a half-share from Edward Alleyn on 20 May 1622.

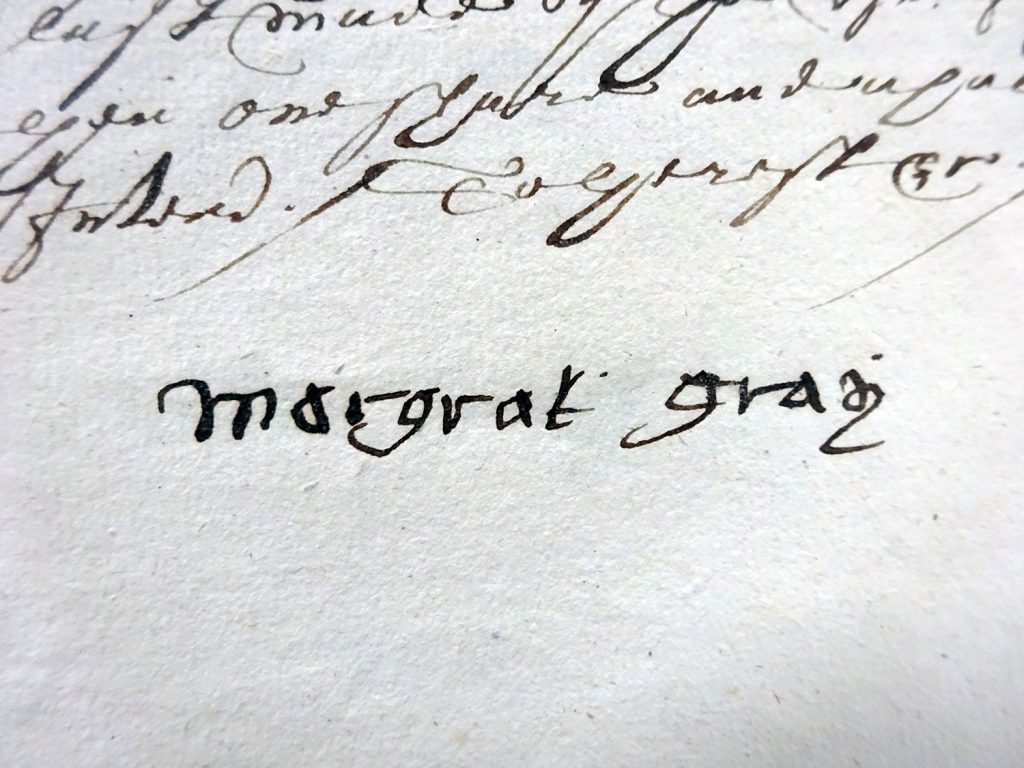

Margaret Gray (c. 1562-1648) (leaseholder 1623-1639). She leased from Alleyn one half-share on 1 August 1623, one full share on 29 January 1624, and another half-share on 21 April 1624. Another half share was mortgaged to her by Eleanor Massey in October 1623.

Mary Fitch Symonds Bryan (c. 1557-1626) (leaseholder 1624-6). Widow of Robert Symonds, haberdasher, and of Luke Bryan, Yeoman of the Guard. She leased a full share from Alleyn on 24 March 1624.

Eleanor Coleman Massey (fl. 1605-35) (leaseholder 1625-34). Widow of the actor Charles Massey, whose half share she inherited. From October 1623 it was mortgaged to Margaret Gray.

Margaret Wayte Wigpitt (fl. 1609-1630) (leaseholder 1626-8). Widow of Thomas Wigpitt, bricklayer, whose half share she inherited.

Thomasine Astley (fl. 1627-42) (leaseholder 1627-35, 1642-9). Granddaughter of Thomas Gilbourne, merchant taylor, who held a full share. When he died in 1627, Gilbourne left it to his daughter, Anne, and his granddaughters, Thomasine and Margaret, in a complex arrangement in which it went to Thomasine and Margaret during the lifetime of their father, Richard Astley, and after his death to Anne. Thomasine regained the share in 1642 when her mother died.

Margaret Astley (fl. 1627) (leaseholder 1627-35). Granddaughter of Thomas Gilbourne.

Elizabeth Massey (fl. 1634-5) (leaseholder 1634-5). Widow of George Massey, merchant taylor, whose half share she inherited.

Rebecca Dunn Warren Fisher (fl. 1605-39) (leaseholder 1634-?38). Daughter of Cuthbert Dunn, farrier, and widow of Simon Warren, merchant taylor, whose half share she inherited.

Sara Massey Hawley (1606-39) (had an interest in a share c. 1634-5). Daughter of the actor Charles Massey and his wife, Eleanor, and the wife of another actor, Richard Hawley. She seems to have had an interest in the share inherited by her mother.

Anne Gilbourne Astley (1594-42) (leaseholder 1635-42). Daughter of Thomas Gilbourne. She inherited his share after the death of her husband, Richard Astley, in 1635.

Grace Fulwell Smart Rhodes (fl. 1607-35) (leaseholder c. 1635). Widow of John Rhodes, vintner, from whom she inherited a full share; she left it to her brother, William Fulwell, in her will.

Susan Shore Browne Greene Baskerville (1573-1649) (leaseholder 1635/6-49). Widow of the actors Robert Browne and Thomas Greene. In 1635 she acquired the half share formerly held by Frances Juby.

Sara Jackson Blomfield (c. 1606-40) (leaseholder 1636-9). Widow of Edward Jackson, a clerk in the Custom House, whose full share she inherited.

Rose Walrond Hill (fl. 1598-1639) (had an interest in a share 1638-9). She inherited an interest in the share of Sarah Blomfield, which had been mortgaged to her husband Lawrence Hill, grocer.

Anne Hudson Morrant (fl. 1610-40) (leaseholder c. 1639). Daughter of Richard Hudson, stationer, and wife of Edward Morrant, stationer and later brewer. She inherited her husband’s full share and two half shares.

Mary Walker Minshawe (1604-42) (leaseholder 1639-42). In 1639, 2½ shares formerly belonging to Margaret Gray and Mary Bryan were acquired in trust for Mary and her sister, Susan Cade. Mary’s husband Edward Minshawe, player, musician and stationer, was also a Fortune leaseholder.

Susan Cade (fl. 1610-39). Sister of Mary Minshawe.

Elizabeth Birt Shank (fl. 1634-40) (leaseholder c. 1639). Wife of the actor John Shank Jr. She acquired a half share in 1639.

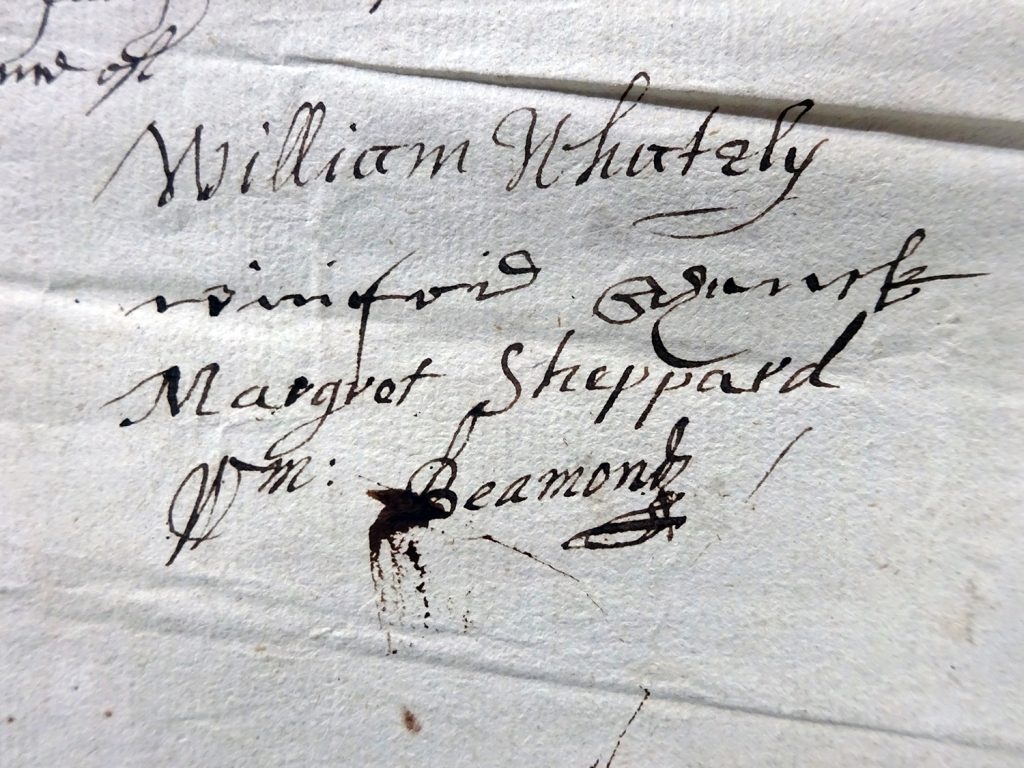

Winifred Shank Fitch (fl. 1610-49) (leaseholder (1640-9). Widow of the actor John Shank and mother of John Shank Jr. She bought two half shares, including one from her daughter-in-law, Elizabeth, in 1640.

Margaret Delahay Santon (fl. 1621-43) (leaseholder 1641-3). Widow of Philip Santon. She inherited his two half shares and left them in her will to her servant Elizabeth Pierpoint.

Anne Minshawe (fl. 1629-49) (leaseholder 1642-9). Daughter of Mary Minshawe. With her brother Arthur she inherited her mother’s interest in 2½ shares.

Susan Cade Jr (fl. 1639-49) (leaseholder c. 1643-9). Daughter of Susan Cade, from whom she inherited an interest in 2½ shares.

Elizabeth Pierpoint (fl. 1643-9) (leaseholder 1643-9). A servant of Margaret Santon, who left her two half shares in 1643.

Most of these women came from what historians have termed the ‘middling sort’ – those who were neither very rich nor very poor. As the Middling Culture project explains, women like these emerged from ‘literate, urban households whose members engaged with a variety of cultural forms for work and beyond’. They were the daughters, wives and widows of London tradesmen, officials and actors. Many of them had enough literacy to leave signatures or complex marks on legal documents such as wills and depositions.

We do not have space here to tell the stories of each of these women, but here are some highlights.

Margaret Gray, the Great Survivor

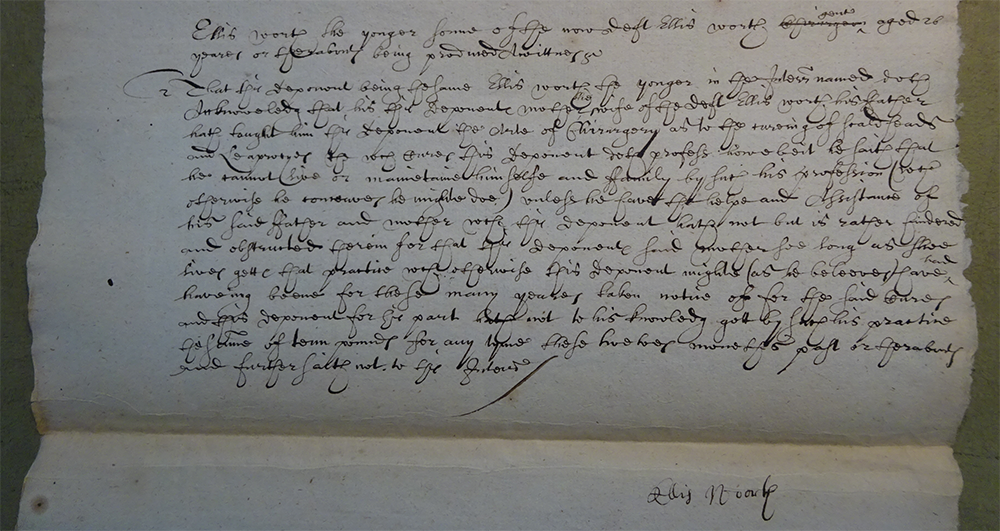

The most enduring leaseholder in the history of the second Fortune playhouse was a London widow, Margaret Gray. For at least 16 years she held one full share and two half shares in her own right, having leased them from Edward Alleyn. Eleanor Massey then mortgaged another half share to her in 1623, meaning that Margaret controlled a full share and three half shares, nearly a quarter of the 12 shares into which the Fortune lease was divided. In 1639, a long dispute between Margaret and Dulwich College ended with the College forcibly taking back her shares. She continued, however, to claim her right in them – in 1646 she gave evidence in a lawsuit involving the College and asserted that her leases were ‘still in force and being’.[6] We haven’t yet been able to find out much about her background or family, but she signed her own name on her deposition, which suggests that she had received some formal education.

Margaret claimed in her deposition that she was ‘aged 84 years or thereabouts’. If this was true, she was in her early 60s when she took on her first Fortune lease, making her a notable example of an economically independent older woman in seventeenth-century London.

Theatrical Connections

Some of the women who had a financial stake in the Fortune playhouse already had strong connections with the theatre. Eleanor Massey inherited a half share from her husband Charles Massey, an actor at the first Fortune and colleague of Edward Alleyn. Her daughter, Sara, who claimed an interest in Eleanor’s share in the mid 1630s, was married to another actor, Richard Hawley. Other theatre women actively sought out investments in the Fortune. Frances Juby acquired a half share from Alleyn in 1622, four years after the death of her husband, Edward, another long-term colleague of Alleyn. In 1635, a few years after Frances’s death, her half share was taken on by Susan Baskerville. Susan was the widow of two actors, Robert Browne and Thomas Greene, from whom she inherited a stake in the Red Bull playhouse; her third husband, James Baskerville, appears to have married her bigamously and eventually deserted her.[7] She acquired her share from John Shank Jr, son of the famous comic actor John Shank and himself an actor at the Fortune.

The Shank family played a prominent role in Fortune shareholding. In 1634, when he was only 17, John Shank Jr married Elizabeth Birt, sister of William Birt, a locksmith from Whitechapel, who came into possession of Frances Juby’s half share after her death in 1631. In 1635, John acquired William’s share, selling it later that year to Susan Baskerville. Three years later, having apparently spent all her money, John abandoned Elizabeth and moved to Ireland to perform at the Werburgh Street playhouse in Dublin. According to William’s bill of complaint in a later lawsuit, Elizabeth’s ‘kindred and friends’ raised the sum of £20 to support her in John’s absence.[8] When John returned from Ireland, he urged Elizabeth to invest her money in the Fortune, allegedly promising that she would keep the ‘issues and profits arising thereby’. In May 1639, a half share was accordingly acquired and put in trust for Elizabeth. However, John broke his promise, took possession of the share, and eventually sold it to his mother, Winifred Shank Fitch. This story is not visible in the rent books at Dulwich College, which only feature John Shank, and it would have been lost if William had not gone to court on his sister’s behalf.

Winifred Shank Fitch’s playhouse investments were more successful than those of her daughter-in-law, but she was also struggling with an unhappy marriage. Winifred’s first husband died in January 1636 and a year later she married Stephen Fitch. He appears to have married her for her money and was outraged when it turned out that Winifred had protected herself against him ahead of the wedding by somehow getting him to seal a bond that meant she kept control over £400. By early 1638 the pair had separated, and when Winifred bought two half shares in the Fortune in 1640 she did so entirely on her own behalf. She is only ever called ‘Shank’ in the rent books at Dulwich College, and when she witnessed the will of Judith Merefield in 1645 she signed her name ‘Winifrid Shanck’.

The Fortune, London and Global Trade

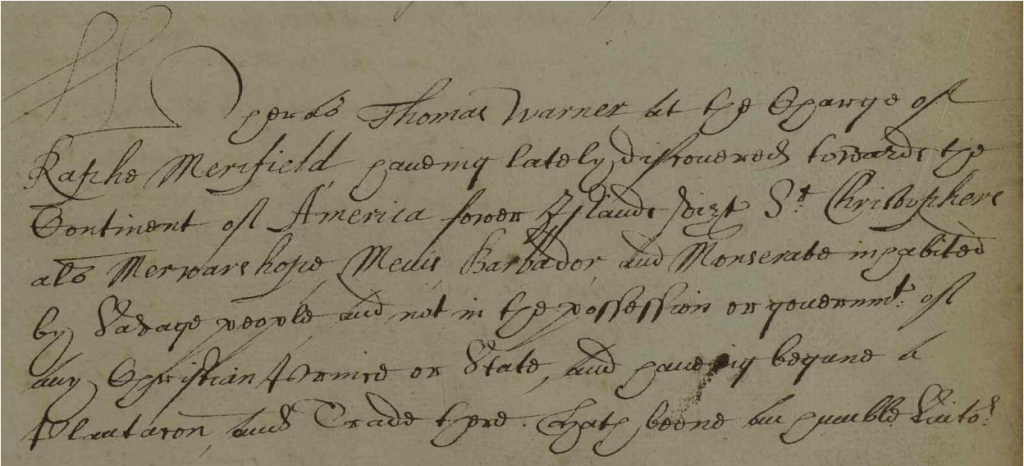

Other networks to which these women belonged connected the Fortune with the livery companies of London and with England’s activities in global trade – especially, but not only, in the Islamic world – and colonisation. They are thus part of what the Medieval and Early Modern Orients project describes as ‘the intersecting webs of our pasts’.[9] William Birt’s lawsuit tells us that Elizabeth Shank’s Fortune share was bought from John Joyce, who was eager to sell quickly because he was ‘bound for Virginia, beyond the seas’. Earlier scholars thought that Mary Bryan was married to an actor, but her life actually links the playhouse with London’s trading networks, the English Midlands, and the Far East. She was the daughter of Thomas Fitch of Mackworth, Derbyshire, and sister of the merchant Ralph Fitch, who travelled to India, Burma and Malaysia, and published an account of his travels in Richard Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations (1599). She was married first to Robert Symonds, a London haberdasher, and later to Luke Bryan, a Yeoman of the Guard.

Mary Minshawe and Susan Cade were the nieces of John Ball, a merchant who traded in North Africa and Constantinople in the early seventeenth century. By the late 1630s, Ball was suffering from severe mental illness, and in 1639 his estate was brought under the control of the Court of Wards. His nieces were granted £10 per annum each during his lifetime for their maintenance and they looked for ways to invest it. The two women already had links with the Fortune: Mary’s actor husband, Edward, had held a half share in the Fortune since 1638; and Tobias Lisle, one of Ball’s trustees, had held a half share since 1635. Lisle acquired 2½ shares formerly belonging to Margaret Gray and Mary Bryan in trust for Mary and Susan. Their interest in the Fortune was later inherited by their children, Anne and Arthur Minshawe and Susan Cade Jr, who sued the College over the playhouse leases in 1649.

Performance at the Fortune

These women’s activities as leaseholders took place against a broader context of performance at the Fortune. The playhouse’s history encompasses political insurgency, the activities of women as managers and performers, and histories of trans and nonbinary identities.

In the period between 1626 and 1649, the Fortune appears regularly in the records of the Master of the Revels, Henry Herbert, who not only organised performances at court but also licensed playing companies and other kinds of performance, and acted as the official censor. Herbert had his work cut out with the Fortune. In May 1639, in the midst of controversies over the place of ritual and ceremony in Protestant religious practice, it staged a play that was interpreted as criticising the Church of England. Edmund Rossingham wrote to Edward Conway, 2nd Viscount Conway, a politician who was also an important patron of poets, reporting that ‘the players of the Fortune’ had been fined £1000 for ‘setting up an alter, a basin and two candlesticks, and bowing down before it upon the stage’. The company claimed that they were reviving an old play and that it did not represent a Christian ceremony but ‘an alter to the heathen gods’; Rossingham comments, however, that ‘it was apparent that this play was revived of purpose in contempt of the ceremonies of the Church’.[10]

£1000 would have been a significant fine – The National Archives’ currency converter suggests that it would be nearly £120,000 in today’s money – but it didn’t deter players at the Fortune from staging controversial material. On 8 June 1642, two months before the outbreak of civil war in England, the actor-dramatist John Kirke paid Herbert £2 for licensing a play on current politics called The Irish Rebellion; on the same day Herbert refused to license another play, describing it as ‘a new play which I burned for the ribaldry and offence that was in it’ but still charged Kirke £2 nonetheless.[11]

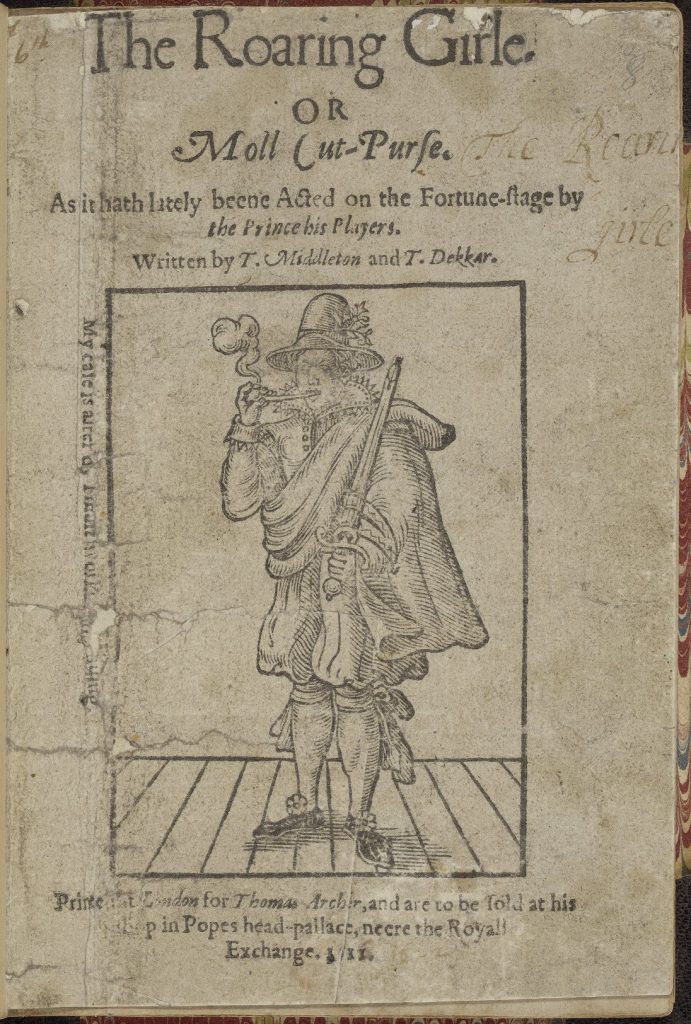

The Fortune companies of this period also performed plays dealing with gender relations, another hot topic in the period. In 1639 the playhouse hosted plays called Woman Monster and A Queen and No Queen, which were licensed by Herbert but are sadly now lost. The early 1640s are also likely to have seen a revival of an old Fortune favourite, Thomas Dekker and Thomas Middleton’s The Roaring Girl, a play dealing with the career of the real-life London character Mary Frith, known as Moll Cutpurse, who was attacked by the authorities for wearing male clothing and performing a song to a lute at the side of the stage in the first Fortune playhouse in 1611. Frith is a figure of complex identities who may have relished the freedom offered by new ways of describing gender in the early twenty-first century.

We don’t know to what extent the Fortune leaseholders supported the artistic policy of the players, but the rent books at Dulwich show that none of them gave up their shares in protest.

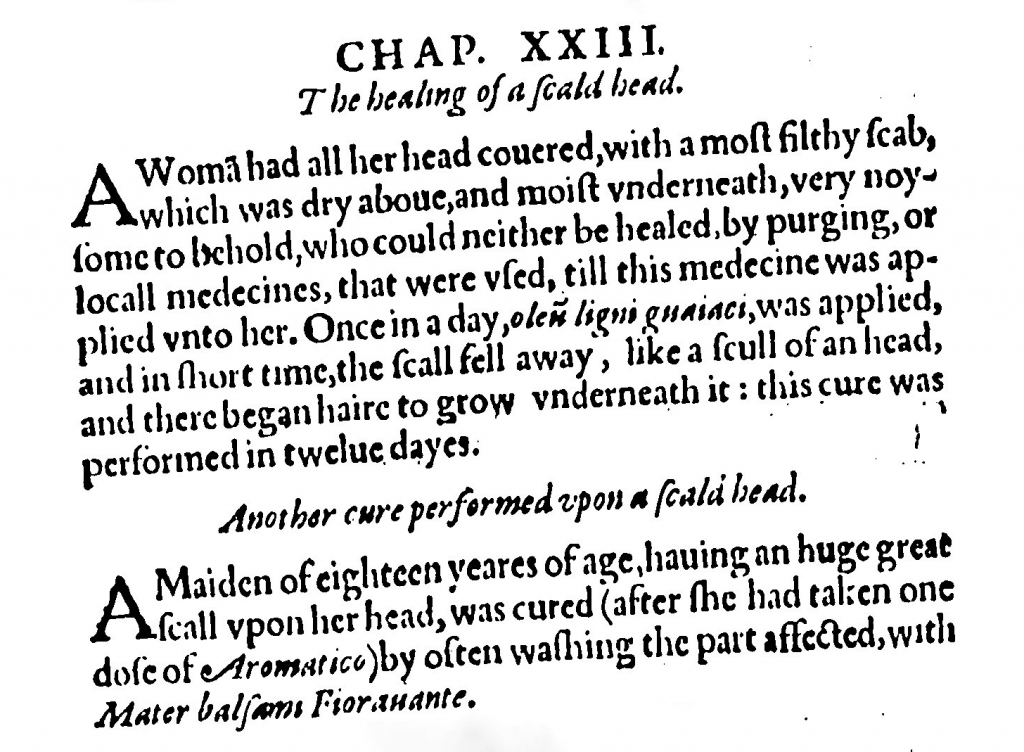

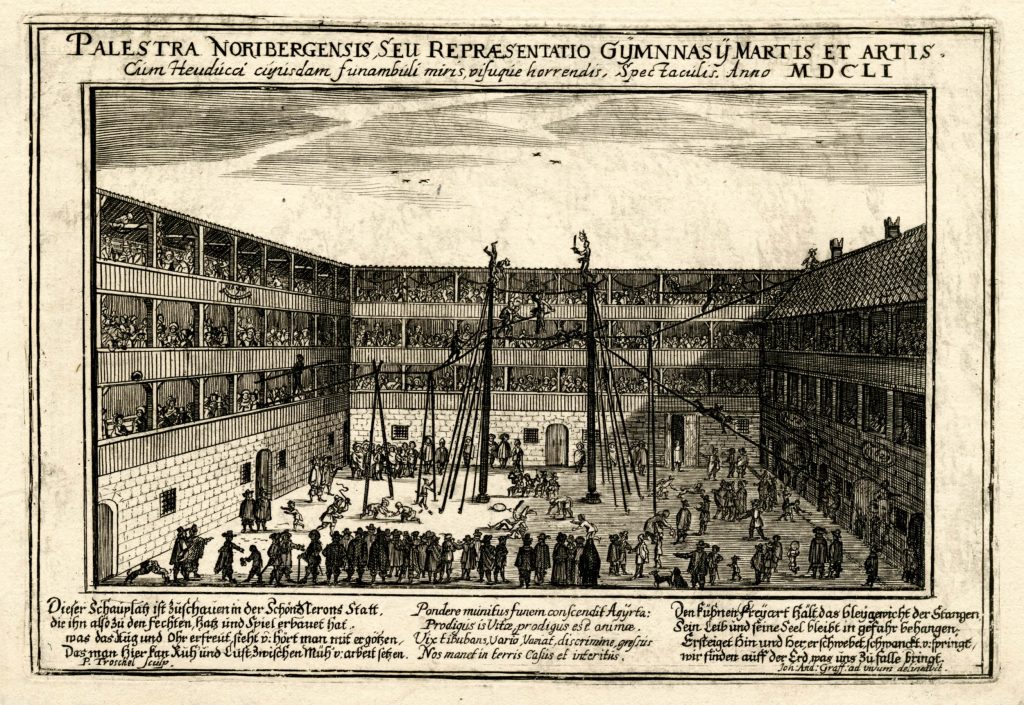

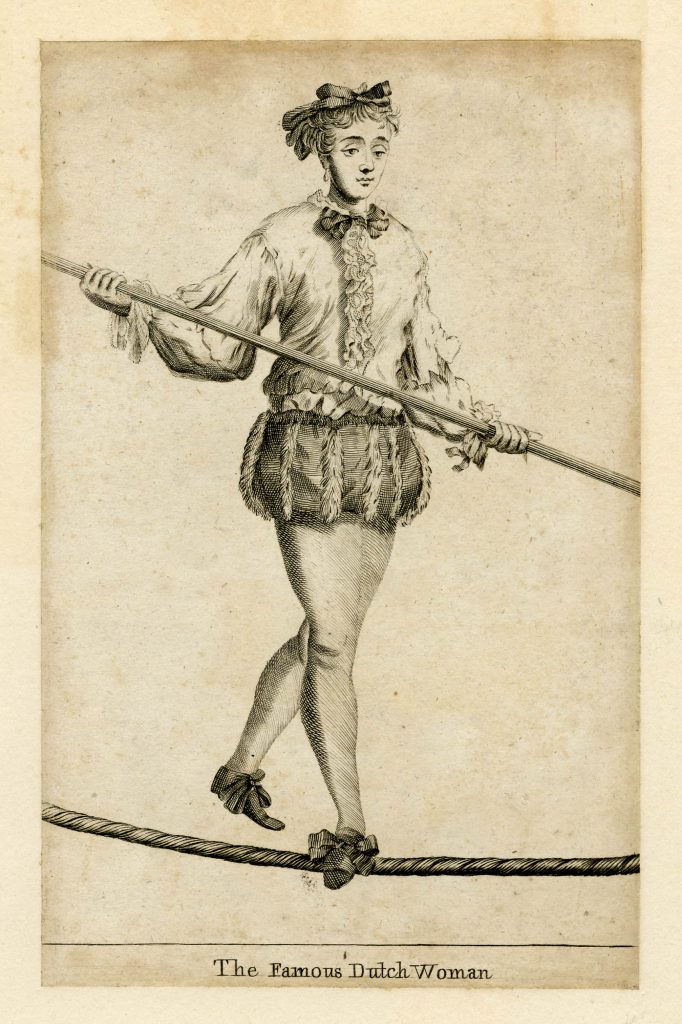

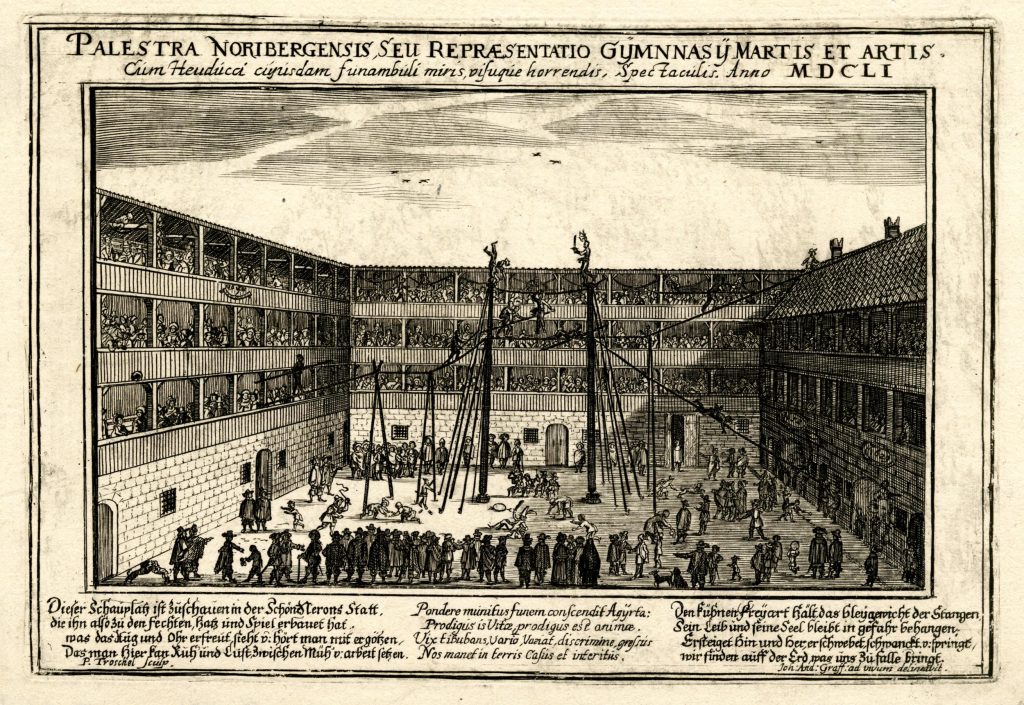

Feats of Activity

Alongside plays, the Fortune also staged feats of activity such as rope-dancing, a mode of performance that involved men, women and children and which was ubiquitous across Europe and into the North African littoral. Rope-dancing could be put on in playhouses, inn-yards, town squares or in the street. Using an easily assembled kit of ropes and poles, rope-dancers leapt, walked, and ran on the tight rope; they spun around the slack rope, hung from it by their legs or feet, or lounged on it in a display of impossible leisure; they ran up or ‘flew’ down sharply angled ropes on the diagonal.

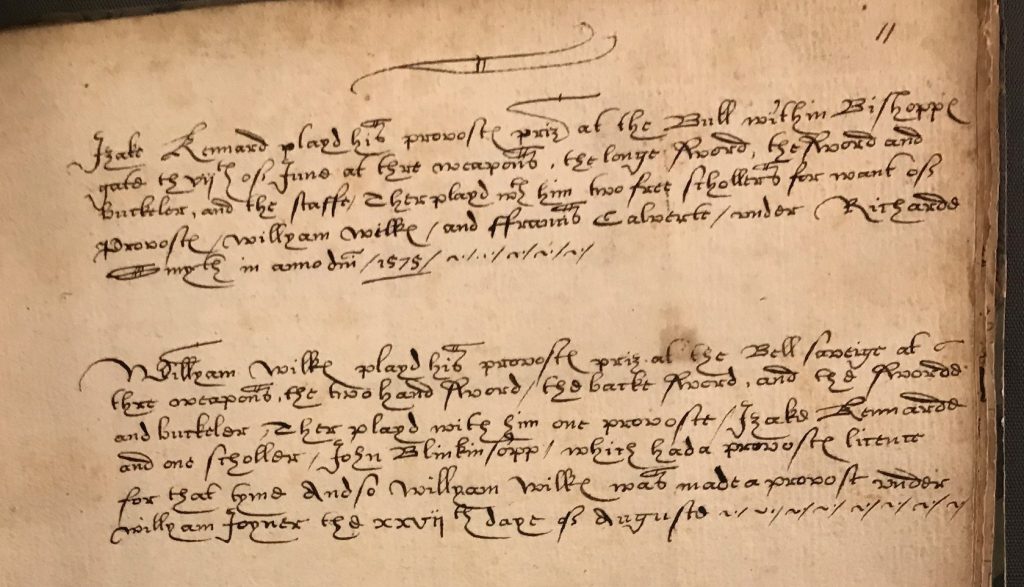

We know that rope-dancing was taking place at the Fortune from at least the 1620s because the Master of the Revels also sought to control these performances. Surviving transcriptions from Herbert’s records show in addition that there was another woman working behind the scenes at the Fortune. On 19 March 1624 ‘Mrs Gunnell’ paid Herbert 10s. to license ‘a masque for the dancers of the ropes’: in this record we see Elizabeth Gunnell, wife of the Fortune actor and leaseholder Richard Gunnell, working alongside her husband in the management of the playhouse.[12] Rope-dancing formed a significant portion of the Fortune leaseholders’ income. In a lawsuit in 1641, Tobias Lisle described the performance of ‘dancing on the ropes and other exercises’ at the Fortune, commenting that the investors received their share of the proceeds ‘every night of the day wherein such dancing and exercises were had’.[13]

One group of tumblers and rope-dancers had a particularly strong connection with the Fortune: a well-established multi-generational family troupe called the Peadles, who were based in London and in Flushing in the Netherlands. By the early 1630s they had been touring southern England, the Midlands and continental Europe for over thirty years; they had played at the English courts of James VI and I and his wife, Anna of Denmark, and at the court of the Elector of Brandenburg. Their number included William Peadle Sr, who rented property within the Fortune complex in the early 1620s, his sons Abraham – who lived in an alley off Golding Lane in 1623 and was described in 1624 as an actor at the Fortune – and William Jr, and Cicely, William Jr’s wife.

Evidence from the 1630s suggests that Cicely was both a performer and, at one point, the leader of the troupe itself. In 1631, the Master of the Revels issued a licence to ‘Cicely Peadle, Thomas Peadle her son, Elias Grundling and three more in their company to use and exercise dancing on the ropes, tumbling, mauling and other such like feats which they or any of them are practised in or can perform’. As Sara Mueller noted in 2008, Cicely’s name appears on the licence in the place where the name of the troupe leader is usually found.[14] Cicely seems to have taken over the troupe in the early 1630s during hard times for the Peadles: two years after the licence was issued, Thomas Peadle was arrested for stealing ruffs from a hedge in Wells, Somerset. We have not yet found any proof that Cicely led the troupe on the Fortune stage, but the evidence that she was a performer, the clustering of Peadle family members around the Fortune complex and Golding Lane, and the fact that we know that rope-dancing took place at the Fortune mean that it is quite likely that she performed there.

Our new research reveals that the Fortune playhouse was an important site for women’s activities as theatre investors, managers and – quite possibly – performers. In turn, the careers of women such as Cecily Peadle and Mary Bryan connect its activities to broader networks of performance, trade and investment, in London, across England and across the globe.

Note: We are very grateful to the Leverhulme Trust for awarding us a Research Project Grant (RPG-2019-215) and the Folger Shakespeare Library and the Huntington Library for awarding us research fellowships during which some initial research was undertaken. We would especially like to thank for their support Calista Lucy, Keeper of the Archive at Dulwich College, and Dr Daniel Gosling, Legal Records Specialist (Early Modern) at The National Archives.

[1] Lucy has led on research into women’s investment in the Fortune, and Clare has led on research on women’s performance there. We have co-authored this post and we are working on a co-authored essay that will set out our findings in more detail.

[2] Dulwich College Archives, Muniments, Series 1, 58, https://henslowe-alleyn.org.uk/catalogue/muniments-series-1/group-058.

[3] S.P. Cerasano, ‘Women as Theatrical Investors: Three Shareholders and the Second Fortune Playhouse’, in Readings in Renaissance Women’s Drama: Criticism, History, and Performance, 1594-1998, ed. S.P. Cerasano and Marion Wynne-Davies (London: Routledge, 1998), 87-94.

[4] John Payne Collier, Memoirs of Edward Alleyn (London, 1841), 194. Matthias Alleyn was a cousin of Edward Alleyn and held the offices of Warden (1626-31) and Master (1631-42) of Dulwich College.

[5] George F. Warner, Catalogue of the Manuscripts and Muniments of Alleyn’s College of God’s Gift at Dulwich (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1881); William Young, The History of Dulwich College (Edinburgh: Morrison and Gibb, 1889); Francis B. Bickley, Catalogue of the Manuscripts and Muniments of Alleyn’s College of God’s Gift at Dulwich, Second Series (London: Governors of Dulwich College, 1903). Warner catalogues and describes some of the copies of legal documents among the papers at Dulwich (see vol. 1, 54-6, 245-7), which suggested to us that other women were involved in the Fortune. Young transcribes – albeit not always accurately – the account for 1626-7 from the Register Book of Accounts, Dulwich College MSS, Second Series, 27, and cites other documents in the Additional MSS, for which a catalogue has not yet been published (see vol. 1, 97-100, 103, 122; vol. 2, 263, 264). Bickley catalogues the Register Books and Rent Books.

[6] Deposition of Margaret Gray, 9 August 1646, in Tobias Lisle v. Thomas Alleyn, Master of Dulwich College, Court of Chancery, 1645-6, The National Archives (TNA), C 24/695/40.

[7] For a valuable summary of Susan Baskerville’s life and engagement with the theatre, see Eva Griffith, Baskervile [née Shawe], Susan’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004), https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/74435.

[8] William Birt v. Tobias Lisle, John Shank Jr and Winifred Shank Fitch, Court of Chancery, 1640, TNA, C 2/ChasI/B54/63.

[9] We are also indebted here to ongoing scholarship that rethinks early modern English literary cultures through their connections to global and colonial trade, stimulated by Kim F. Hall’s Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995), and examined in another theatre-historical context in our earlier blog.

[10] TNA, SP 16/420, f. 266.

[11] N.W. Bawcutt, ed., The Control and Censorship of Caroline Drama: The Records of Sir Henry Herbert, Master of the Revels 1623-73 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 211.

[12] Bawcutt, ed., Control and Censorship, 161,

[13] John Beale v. Thomas and Mathias Alleyn and Tobias Lisle, Court of Chancery, 1641, TNA, C 2/ChasI/B44/13.

[14] Sara Mueller, ‘Touring, Women, and the English Professional Stage’, Early Theatre 11 (2008), 53-76.