This post explores the role of women in early English playhouses, drawing on Before Shakespeare research (and it also appears on the Before Shakespeare blog). Stay tuned for research posts from Engendering the Stage in the coming weeks.

The crossovers between the research projects Before Shakespeare and Engendering the Stage were raised several times across the latter’s workshop residency at the Stratford Festival Laboratory in September 2018. This “mash-up” blog brings the projects directly together. Indeed, Engendering the Stage is planning a series of blog posts expanding on the broader research topics under its remit—and would also welcome proposals for such posts. This particular piece gestures, briefly, to some of the cross-pollination between theatre history, performance, and the playing industry by considering just one of the points of overlap between Before Shakespeare and Engendering the Stage—in this case, land and property ownership related to commercial playhouses.

There are many forms of labour involved in the early modern playing industry in England: some on-stage; some immediately off- and around-stage; and some concerning the land on which stages are situated. On the latter, much ink has been spent exploring some of the major (male) figures involved with buying land or renting property, building and converting tenements, and pulling together—through a variety of approaches—a playhouse.

There are reasons why apparent big-hitters in the industry like James Burbage, John Brayne, and Philip Henslowe take centre stage: partly because many are chief movers behind these ambitious and unusual ventures, but also because the above narrative is based on a narrow sense of what a “playhouse” is and on who might be instrumental to its wider development and existence. Women’s involvement in the transactions and legal exchanges that underpin playhouse ownership has been less discussed, though we are becoming increasingly aware of the significance of a host of figures central to this history. A quick survey of the evidence related to London’s diverse early commercial playing spaces suggests that women occupied a serious and significant presence in early modern playhouses.

***

Both before and after The Theatre—the amphitheatrical structure in Shoreditch—was built, plays took place in inns across London. Andy Kesson has written on the Before Shakespeare website about these spaces and their relative neglect in theatre history narratives. Recently, David Kathman’s expansive work on the subject has uncovered new leads, figures, and details that help us understand playhouse inns more clearly.

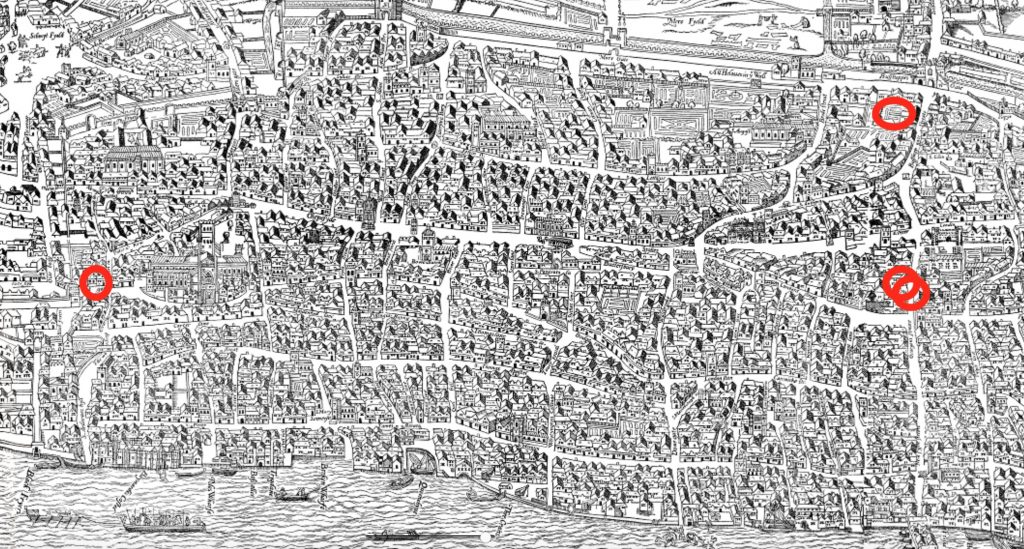

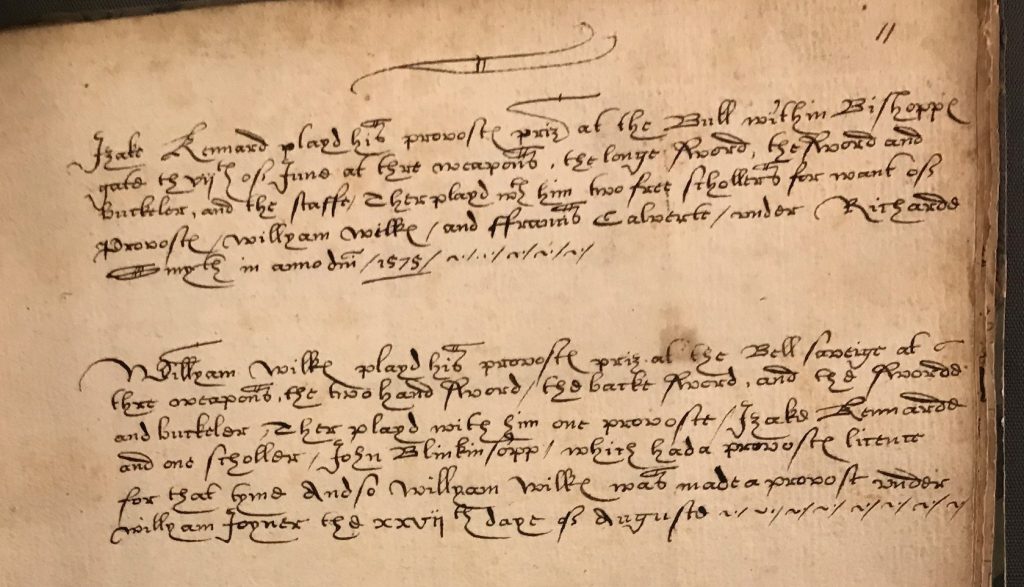

Spaces such as the Bel Savage (Ludgate Hill), the Bull (Bishopsgate), the Bell (Gracechurch St.), and the Cross Keys (Gracechurch St.) were regular venues for playhouse activity—that is, for plays, for fencing prizes, and for extemporal feats and shows. A forthcoming blog on Engendering the Stage from Clare McManus will explore women’s skilled performance in such feats. Stephen Gosson explains how he enjoyed “two prose books played at the Bel Savage” in the late 1570s (School of Abuse, 1579); in 1577, the Office of the Revels transported a presumably elaborate prop (a “counterfeit well”) from the Bell to St John’s in Clerkenwell for “the play of Cutwell” (TNA AO3/907/5); John Florio’s advice to Italian language learners answers the question, “Where shall we go?” with the appealing answer “To a play at the Bull, or else to some other place” (First Fruits,A1r [1578]); and James Burbage himself is arrested wandering (perhaps from his own playhouse) to see a play at the Cross Keys in the 1590s.

These were playing spaces owned and/or run by women. Kathman explains that “three of these four inns were owned or leased by women during their time as playhouses. Margaret Craythorne owned* the Bell Savage from 1568 until her death in 1591 [*or rather likely leased it from the Cutlers’ Company, as Tracey Hill informs us], Alice Layston owned the Cross Keys from 1571 until her death in 1590, and Joan Harrison was the proprietor of the Bull from the death of her husband Matthew in 1584 to her own death in 1589” (“Alice Layston at the Cross Keys,” Medieval & Renaissance Drama in England 22 (2009): 144; see also Kathman’s other invaluable publications on these subjects).

Female ownership of such spaces is by no means untypical across the capital in this period, partly because widows inherited property from their husbands and thereby gained a degree of independence and business freedom they may not easily come by earlier in life. There are numerous examples of landladies across the capital, for instance, adapting spaces and converting “alleys” into packed residential quarters. Margaret Hawkins is repeatedly cited by the Court of Aldermen in the 1570s for having “diverse times tenants dwelling in Alleys & other places…” (REPS 17, 427v; 20 Jan. 1573). In his misogynsitic sketch of alley owners—who monopolise food and drink sales for their alley-dwellers to create an in-house market—Henry Chettle chooses the landlady rather than the landlord to exemplify these nefarious practices (Kind-Harts Dream, 1593).

There is a close relationship between domestic alleys and alleys adapted for recreational use—in particular bowling alleys. Such alleys are themselves influences on the converted buildings that make up the majority of sixteenth-century playhouses. In this regard, landladies like Margaret Hawkins contribute to the development of domestic and recreational space that has significant bearing on the theatre industry. It is perhaps no surprise, then, that three women operated the highly successful playhouse inns at the Cross Keys, the Bel Savage, and the Bull—spaces that preceded The Theatre and the Blackfriars as playing venues and continued for decades to attract paying audiences as well as diners, tipplers, and guests. Eliding “inns” from the traditional playhouse narrative not only generates misleading notions about the antitheatrical zealousness of the “City” and limits our understanding of the contexts, architecture, and experience of playhouses, it also eclipses the role played by landladies in London’s leisure ecology.

Women also lay claim to amphitheatrical spaces. John Brayne, co-founder of the Theatre with James Burbage, died in 1586, from which time his widow Margaret sought to exercise her rights to the building and its profits. As well as conducting a protracted legal battle that raged on even after her death, Margaret Brayne placed herself at the doors of the Theatre in an attempt to collect playhouse entry prices directly. A young deponent in one of the law cases, Ralph Miles, explained how he was

requested by Margaret Brayne and [his father] Robert Miles . . . to go with them to the Theater upon a play day to stand at the door that goeth up to the galleries of the said Theater to take and receive for the use of the said Margaret half the money that should be given to come up unto the said Galleries at that door.

(The National Archives, C24/228/10)

In a heated altercation, “Richard Burbage and his mother [Ellen] set upon” Miles, “with a broomstaff calling him murdering knave with other vile and unhonest words” (C24/228/10). The incident shows two women—Margaret Brayne and Ellen Burbage—laying claim to theatrical space and asserting their own agency, ownership, and investment in the playing industry.

Moreover, The Theatre was in a (somewhat enigmatic) commercial relationship with its neighbouring playhouse, The Curtain, during these years, and Margaret Brayne also laid claim in her lawsuit to half the profits of that space. The extensive documentation arising from these various Theatre-related suits shows Brayne asking the courts to take her seriously as a playhouse proprietor—and a major figure of theatrical Shoreditch; now, these records ask us to do the same.

Leases pertaining to the Curtain in the years before Margaret Brayne’s activity show that Alice German was central to the ownership of the Curtain land, which she secured for her son Mawrice Long in the late 1560s and 1570s—and there is doubtless much more to discover about these figures and their relationship, or otherwise, to the playhouse that appeared there shortly after their occupation.

In the early 1580s, a little south of Shoreditch in London’s Blackfriars, playhouse proprietor Richard Farrant’s death bequeathed to his widow Anne “the Leaze of my howse in the blacke ffriers in London”—the site of the First Blackfriars Playhouse (1581-2). Anne proceeded to sublet this property and is herself at the centre of a series of correspondence and legal requests pertaining to the property’s use as a playhouse, which Engendering the Stage and Before Shakespeare’s Lucy Munro has been exploring.

These are just a few examples of the evidence related to women’s involvement in the theatre business in sixteenth-century London. Their influence on the stage itself is notable—and it is noted. Margaret Brayne theatrically performing her business claims to the Theatre gives us just one clear example of women “acting” in a playhouse. Similarly, the inn owners who develop models for commercial playhouses in the years before Burbage and Brayne set up The Theatre leave archival traces that help provide some small detail to playhouse ownership. Doubtless, female inn owners were among those targeted by City precepts from as early as the 1540s that sought to regulate “all those in whose houses or other rowmes eny such playes or interludesshalbe made or kepte” (London Metropolitan Archives, REPS 16, Feb. 1569).

Given the involvement of women in the commercial development and managing of playhouses, it is perhaps no surprise that the earliest surviving plays from these spaces focus on female characters and their agency and experiences. The earliest such surviving play, Robert Wilson’s The Three Ladies of London (1581), is framed from the outset as an unashamedly commercial product: “Then young and old, come and behold our wares, and buy them all” (Prologue). It explores the power, sexual and social desires, and struggles of its three title characters—Love, Conscience, and Lucre—and conjures an image in which commercial savvy and success (and greed) are embodied by a woman (and in keeping with the Burbages’ favourite theatre item, it also features broomsticks, which Lady Conscience begins to sell for a living: “New broomes, greene broomes, will you buy any…”; she reassures anybody interested in using them as weaponry: “My broomes are not steeped; but very well bound!”):

LOVE. Tis Lucar now that rules the rout, tis she is all in all:

(1.1.3-17)

Tis she that holds her head so stout, in fine tis she that works our fall [. . .]

For Lucar men come from Italy, Barbary Turky,

From Jewry: nay the Pagan himself,

Indangers his body to gape for her pelf.

They forsake mother, Prince, Country, Religion, kiffe and kin,

Nay men care not what they forsake, so Lady Lucar they win.

In light of Margaret Brayne and Ellen and Richard Burbage’s episode at The Theatre, The Three Ladies of London—in which Lucre features as (among other things) a canny and well-connected businesswoman—is not wholly theatrical fantasy or allegory. Why should it be in a play so heavily textured by realism and the workaday details of the urban world? It was probably played in The Theatre itself and was revived in 1588 and supplied with a sequel in the years when Margaret Brayne was suing for dividends of the playhouse’s profits. Wilson’s play should point us both to the diverse representation of female agency and desire in plays from the overlooked period of the 1580s and to the real women who owned, leased, laid claim to, and ran the very spaces in which those plays were performed.