This is the first in a series of blog-posts that will draw attention to the roles of women in the economic structures that surrounded the early modern stage. These posts derive from our documentary research project, ‘Engendering the Stage: The Records of Early Modern Performance’, funded by a Research Project Grant from the Leverhulme Trust, and they are based on our work in the National Archives, the London Metropolitan Archives and other collections.

Future posts will focus on women’s involvement in the ownership and leases of playhouses, but I want to start by looking at the broader network of financial interactions that supported the playhouses, a network that extended far beyond Britain’s shores. This material was first presented at the ‘Theatre Without Borders’ conference in June 2021 as part of a panel on ‘Staging Bodily Technologies’.

In this post I take a close look at the activities of two entrepreneurial women with connections to the seventeenth-century stage: Frances Worth and Judith Merefield. Both were related to actors and both operated within family networks that link theatre finance with colonial exploitation, in particular the colonization of the West Indies between the 1620s and 1650s.

Frances was born in 1602. The daughter of a painter-stainer, Thomas Bartlett, she was married successively to two actors. In 1620, when she was only 18 years old, she married the 19-year-old Thomas Holcombe. Holcombe was probably still an apprentice at the time, playing female and juvenile roles on the stages of the Globe and Blackfriars playhouses. He died only a few years later, in late August or early September 1625, during a virulent outbreak of plague in London. In January 1626 Frances married for a second time. Her new husband was Ellis Worth, whose long career centred on the Red Bull and Fortune playhouses, where he was successively a member of Queen Anna’s Men, the Revels Company and Prince Charles’s Men.

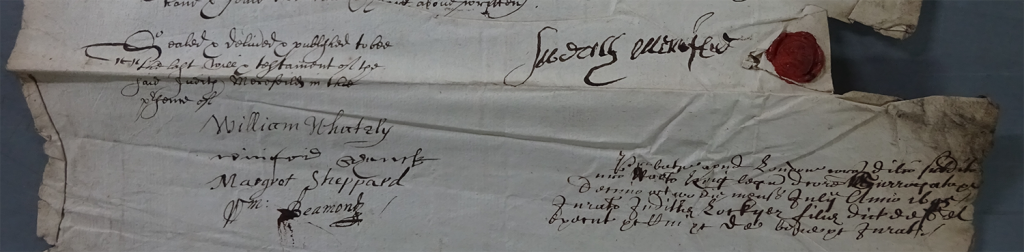

Ten years older than Frances, Judith was the daughter of John Heminges, a long-time actor with the King’s Men – the company of which Shakespeare was also a member – and the master to whom Thomas Holcombe was apprenticed in 1618. Judith was one of fourteen children born to John and his wife Rebecca, of whom six daughters and two sons survived to adulthood. In 1613, at the age of 19, Judith married the 21-year-old Ralph Merefield, a member of London’s Weavers’ Company who also appears to have worked as a scrivener. Heminges appears to have had his daughters as well as his sons educated: when Judith made her will in 1645 she signed it in her own hand, and the will also bears the signature of her sister Margaret Sheppard, who was one of the witnesses.

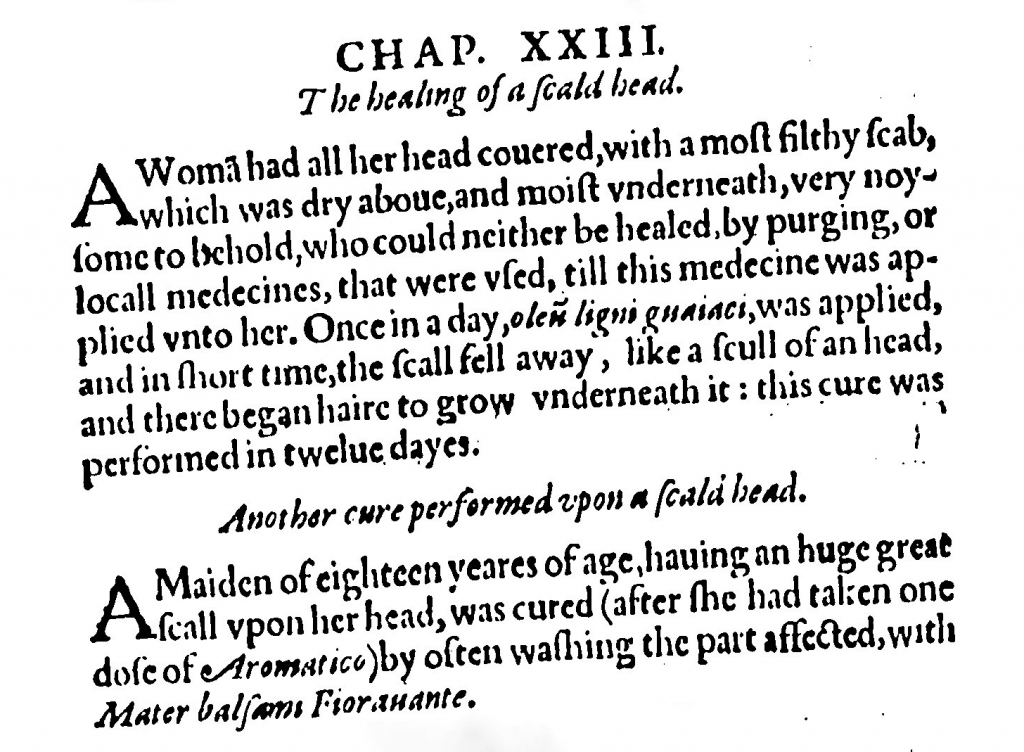

Frances and Judith must have encountered each other many times in the close-knit communities that surrounded and sustained the seventeenth-century stage, and both of their histories reveal women with an entrepreneurial streak. Frances was unusual by seventeenth-century standards in that she exercised her own profession, independent from that of her husbands. On 26 January 1622, during the life-time of her first husband, she was appointed by St Bartholomew’s Hospital in Smithfield, London, as a ‘surgeon’ specialising in curing skin disorders such as ‘scald heads’ and, perhaps, venereal disease.[1] The records of the hospital show that this trade provided her with a lucrative income for many years. By the early 1630s her earnings were regularly topping £100 per annum and she was still being paid for her work by the hospital in the mid 1660s. These wages would have meant that she was earning substantially more than a skilled tradesman, and she also appears to have out-earned her male colleagues at the hospital. In 1629, for example, she earned £58, while the physician William Harvey was paid £33 and the apothecary, Richard Glover, was awarded £40.[2]

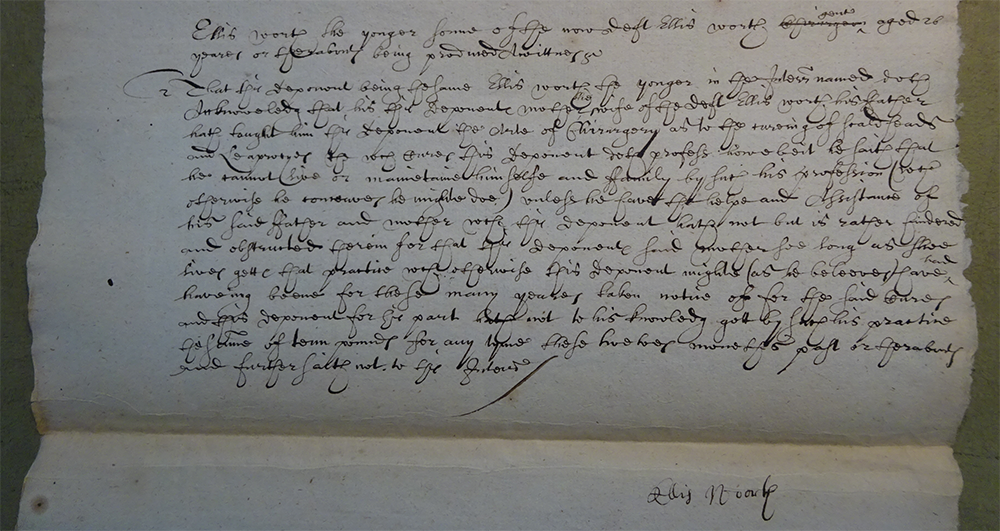

In a lawsuit of the mid 1650s, Ellis Worth refers to the income that his family makes through Frances’s ‘great pains and industry in a way of surgery as relating to St Bartholomew’s Hospital in Smithfield, London, and otherwise’, describing himself as ‘having no trade’.[3] His testimony and that of a series of witnesses make clear both Frances’s status as a surgeon and the importance of her work to the family. Charity Earles, for example, declares that there is ‘none in London or elsewhere that can do the like cure besides the defendant Frances’.[4] The witnesses also offer an account of the way in which Frances has trained her 26-year-old son, Ellis Worth junior, in ‘the art of chirurgery as to the curing of scald heads and leprosies’. [5] Somewhat ungraciously, Ellis junior acknowledges the esteem in which his mother is held but only in the course of complaining that he is ‘hindered and obstructed’ in exercising that ‘art’ for himself because his mother ‘so long as she lives gets that practice which otherwise this deponent might (as he believes) have had’.

Frances’s earnings as a surgeon probably helped to sustain her family’s other activities, which encompassed not only theatrical investment but also investment in England’s colonization of the West Indies. Her stepdaughter, Jane Worth, married as her first husband Henry Ricroft, who invested in the Fortune playhouse alongside Ellis Worth in the early 1630s. Alongside the Fortune, the Ricrofts also invested in a plantation in Barbados, and after Henry Ricroft’s death Jane married another colonizer, Peter Alsop. In his 1659 will, Ellis Worth mentions ‘my daughter Jane Alsop wife of Peter Alsop in Barbados’ and ‘her eldest son Ellis Ricroft which she had by her former husband Henry Ricroft deceased’; as Jennifer L. Morgan points out, Ellis was to make bequests of enslaved people to his own children two decades later. [6]

It is likely that Frances’s substantial earnings financed Ellis Worth’s investment in the Fortune in the 1620s and early 1630s, and they may also have supported the theatrical and colonial activities of the Ricrofts and Alsops. In the 1640s and 50s, when the commercial presentation of plays in London was prohibited and the livelihoods of actors were rendered precarious and at times non-existent, Frances’s trade appears to have been the family’s main source of income and prestige.

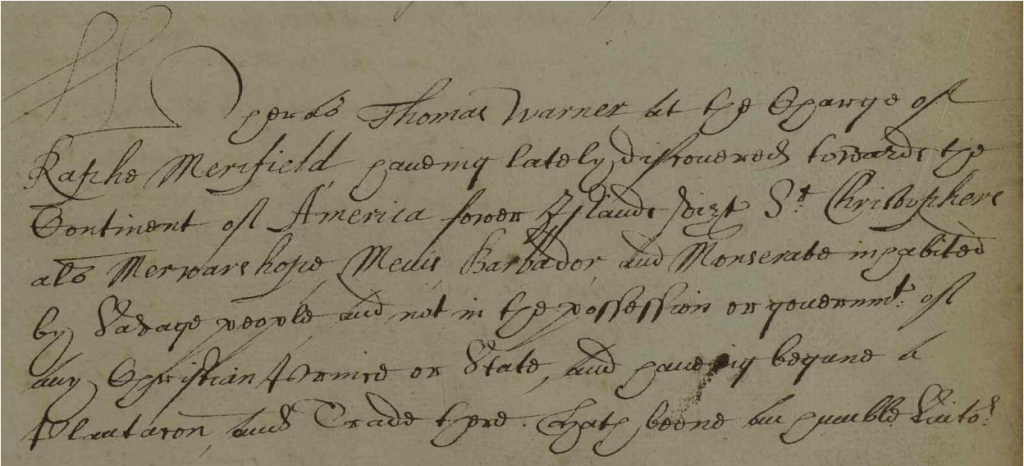

Judith Merefield’s career connects the theatre with colonial projects even more strongly. Her husband, Ralph Merefield, financed the ships that arrived in early 1624 at the island then known as St Christopher, now better known as St Kitts, and called ‘Liamuiga’ or ‘fertile island’ by the indigenous population that was later massacred by the colonizers. On 13 September 1625, Ralph and his partner, Thomas Warner, were issued with a grant that appointed Warner as the colonial governor of ‘Saint Christopher’s alias Merwarshope’, Nevis, Barbados and Monserrat, which were described as ‘inhabited by savage people and not in the possession or government of any Christian prince or state’. The grant also gave Ralph the authority ‘to traffic to and from the said island … and to transport men and do all such things as tend to settle a colony and advance trade there[in]’.[7]

Other members of Judith’s family were also involved in colonial schemes. Her father, John Heminges, was not only a major shareholder in the Globe and Blackfriars playhouses, and one of the men who helped to prepare the 1623 First Folio edition of Shakespeare’s plays, but also an investor in at least two colonial projects. One investment involved his eldest surviving son, also called John; the other was a project that was referred to in a lawsuit after his death in 1630 as ‘a desperate adventure unto the West Indies’.[8] It is highly likely that Heminges invested in Merefield’s expedition, which was being planned and executed at the same time as he was at work on the First Folio, a volume that opens with Shakespeare’s colonial play, The Tempest.[9]

The family’s colonial connections were not limited to Ralph Merefield. The husband of Judith’s sister Rebecca, named as ‘Captain William Smith’ in Heminges’s will, is probably the man of that name who appears to have captained the second ship to St Christopher in 1624 and later travelled there as the captain of another ship, the Hopewell, in October 1627. Two of Judith’s own daughters, Judith and Mary, would go on to marry men involved in colonial trade and exploitation: the privateer and slave-trader William Jackson and Thomas Sparrow, who was governor of Nevis around 1636-7.

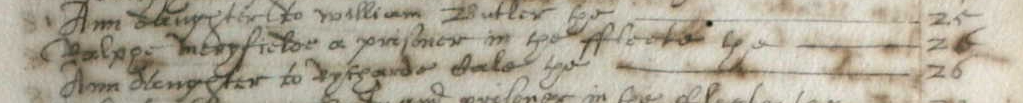

Ralph Merefield quickly exercised the authority granted to him by setting up tobacco plantations on St Christopher.[10] The Cambridge playwright Peter Hausted refers to the pleasures of ‘a thatch alehouse, and St Kitts Tobacco’ in his 1632 play The Rival Friends, suggesting something of the commercial reach of this project.[11] However, Ralph spent well beyond his means in financing the colonization of St Christopher and soon faced financial disaster. He is described in one of the lawsuits connected with John Heminges’s estate as dying ‘a prisoner in the Fleet of little or no estate at all and many hundred pounds in debt’, and his burial is recorded in the register of St Bride, Fleet Street, on 26 December 1631, as that of ‘a prisoner in the Fleet’.[12]

Judith did not simply have a family connection with these activities. After Ralph’s death she appears to have both defended his right to property in the West Indies and to have profited from the trade in tobacco that he established. In 1636, Nicholas Burgh, who accompanied Warner and Merefield to St Christopher and was a co-author of the earliest account of the colonization of the island, claimed that

[Judith] hath received for several parcels of tobacco sent unto her from the Island of Saint Christopher’s by Sir Thomas Warner, governor thereof, as belonging to the estate of the said Ralph Merryfield, several sums of money (that is to say) for tobacco sold to Master Armstrong £9 8s. 6d., for tobacco sent home to her by Captain Paul Thompson £37 15s., for tobacco sent her home in the Adventure £22 10s., for tobacco sent her home by Captain Cork £15 10s., for tobacco brought her home by Sir Thomas Warner £78, amounting in all to the sum of one hundred [and] sixty three pounds or thereabouts[.] [13]

These are substantial sums. According to the National Archives’ historical currency converter, it would have taken a skilled tradesman in the 1630s over six years to earn £163.

The Merefields’ trade in tobacco was indelibly linked to playhouses, where it was sold and consumed. In the early 1630s, the anti-theatrical writer William Prynne decries both actors and playgoers as ‘tavern, alehouse, tobacco-shop, [and] hot-water-house haunters’ (that is, drinkers of strong, distilled spirits), describing a ‘walk’ from ‘a playhouse to a tavern, to an alehouse, a tobacco-shop, or hot-water brothel-house; or from these unto a playhouse’, ‘where the pot, the can, the tobacco-pipe are always walking till the play be ended’. [14] It is not unlikely that some of the tobacco imported by and on behalf of Ralph and Judith Merefield found its way into the Globe and Blackfriars playhouses used by the King’s Men, creating a circuit in which the playhouse investments of men like Heminges fuelled colonial expansion and trade, the products of which were then sold in the playhouse.

The activities of Frances Worth and Judith Merefield bring to the fore a set of transnational networks to which the early modern theatre was connected, pointing not only to London’s developing status as a colonial city but also to the place of its cultural institutions within circuits of colonial trade. Frances’s trade in scald heads would have facilitated her family’s investments in theatre and colonization, while the trade in tobacco from which Judith profited was one of the most tangible signs of theatre’s implication in colonial enterprise and exploitation. Theatre history was shaped not only by generations of assertive and entrepreneurial women but also by the imperialist project of early modern Britain.

By tracing stories like those of Frances and Judith, Engendering the Stage seeks to expand our understanding of the roles that women have played in the history of the stage and also to acknowledge the sometimes troubling aspects of that history.

***

If you are interested in knowing more about early modern women’s involvement in theatre finance, we recommend the following:

S.P. Cerasano, ‘Women as Theatrical Investors: Three Shareholders and the Second Fortune Playhouse’, in Readings in Renaissance Women’s Drama: Criticism, History, and Performance, 1594-1998, ed. S.P. Cerasano and Marion Wynne-Davies (London: Routledge, 1998), 87-94 [This essay examines the investments of Frances Juby, Margaret Gray and Mary Bryan in the second Fortune playhouse.]

Natasha Korda, Labors Lost: Women’s Work and the Early Modern English Stage (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011) {This book discusses the activities of women as investors in theatrical enterprisers, lenders of money within theatrical circles and ‘gatherers’, that is, collectors of money in playhouses.]

The King’s Women 1594-1642 [This new blog by Meryl Faiers, Lucy Holehouse, Héloïse Sénéchal, Jodie Smith and Jennifer Moss Waghorn presents fresh research on the women connected with the King’s Men.]

For further reading on the early modern Caribbean and broader histories of colonization and enslavement, see Vanessa M. Holden and Jessica Parr, ‘Readings on the History of the Atlantic World’, in Black Perspectives.

***

Notes

[1] James Paget, Records of Harvey: in Extracts from the Journals of the Royal Hospital of St. Bartholomew (London: John Churchill, 1846), 36. I have put all quotations from early modern documents into modern spelling.

[2] Norman Moore, The History of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital (London: Pearson, 1918), 230.

[3] Zachary Baggs v. Ellis and Frances Worth, Court of Chancery, 1653-4, The National Archives (TNA), C 7/402/32.

[4] Deposition of Charity Earles in Baggs v. Ellis and Worth, 30 July 1654, TNA, C 24/780/110. This document was first drawn to scholars’ attention by C.J. Sisson in ‘Shakespeare’s Helena and Dr William Harvey’, Essays and Studies 13 (1960), 1-20.

[5] Deposition of Ellis Worth, junior, 25 August 1654, TNA, C 24/780/110.

[6] E.A.J. Honigmann and Susan Brock, Playhouse Wills, 1558-1642 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993), 209; Jennifer L. Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 98.

[7] Grant to Thomas Warner and Ralph Merefield, 13 September 1625, Privy Council Register, 27 March 1625-17 July 1626, TNA, PC 2/33, f. 103r.

[8] Joint and Several Answers in Thomas Kirle v. William Heminges, John Atkins and Judith Merefield, Court of Chancery, 1632, TNA, C 2/ChasI/K5/42. I first encountered this document in 2016 in a transcription among the papers of the early twentieth-century theatre historians Charles William Wallace and Hulda Berggren Wallace at the Huntington Library, San Marino, California. I would like to thank the Huntington Library for awarding me a Francis Bacon Fellowship to look at these materials.

[9] I will write about this connection at greater length in forthcoming work on John Heminges and Henry Condell, and their role in shaping Shakespeare’s plays on page and stage.

[10] Signet and Other Warrants for the Privy Seal, August-November 1626, TNA, PSO 2/67; Privy Council Registers, 1 June 1627-28 February 1628, TNA, PC 2/36, f. 269.

[11] Peter Hausted, The Rival Friends (London, 1632), sig. C2r.

[12] Bill of complaint in Kirle v. Heminges, Atkins and Merefield; Parish Register, St Bride, Fleet Street, London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), P69/BRI/A/004/MS06538.

[13] Answer of Nicholas Burgh in Arthur Knight v. Nicholas Burgh, John Atkins, Judith Merefield, et al., Court of Chancery, 1636-9, TNA, C 2/ChasI/K18/50.

[14] Histrio-Mastix (London, 1633), sig. 2T1v.