We’re here at the end of our first day at the Stratford Festival Laboratory having worked through a variety of questions, possibilities, and avenues—and set up plenty more for the coming week. This post provides a short reflection on our discussions and provides some background to the Stratford Festival Laboratory, as well as a brief summary of our opening workshop activities.

Looking at the past tells us about how the future can be.

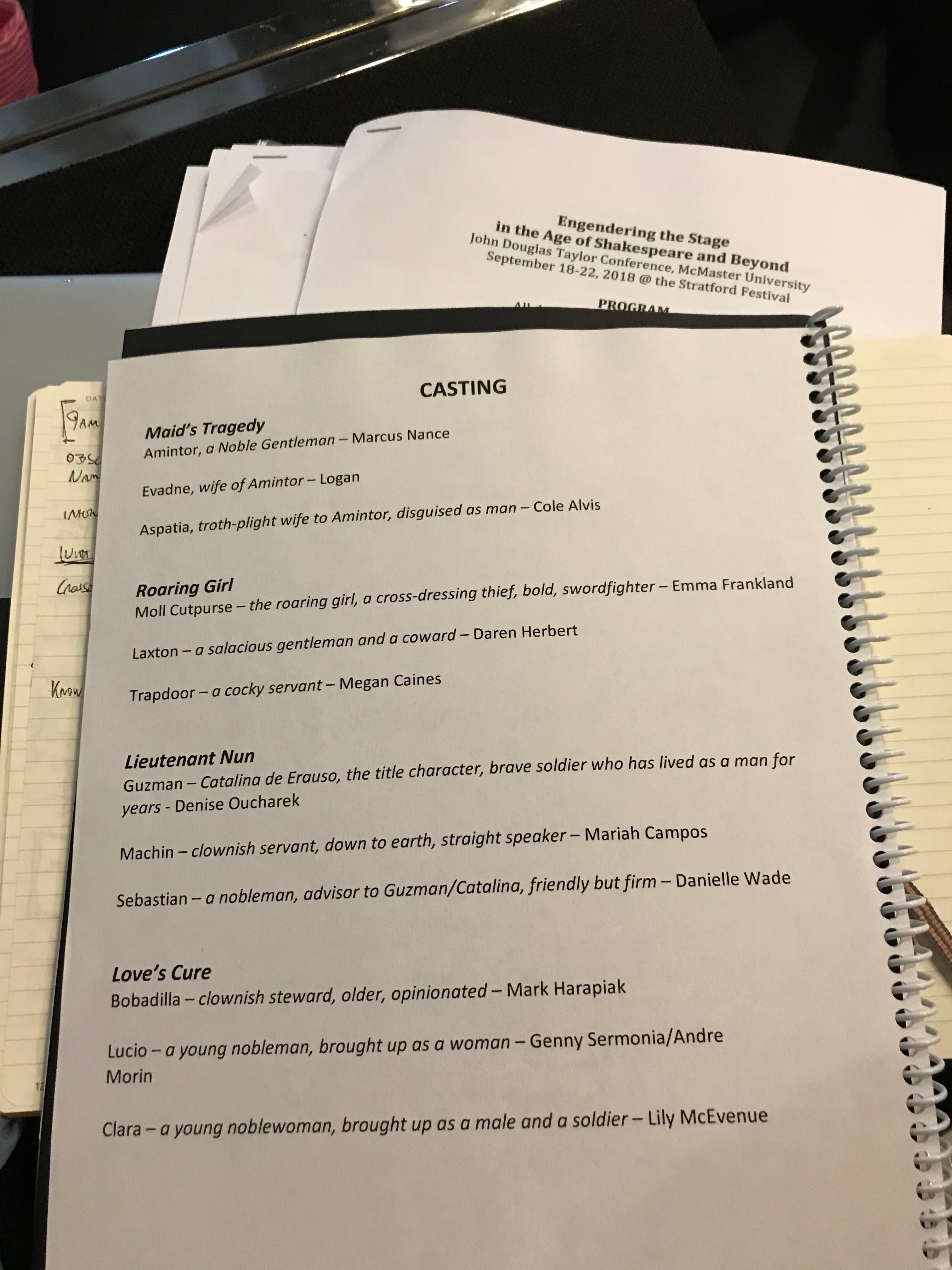

We began with introductions to the room and an outline of the rationale for this week’s conference and our time at the Stratford Lab. Engendering the Stage is interested in thinking about diverse casting practices across classical drama—as informed by both historical practice and contemporary performance practice. Peter Cockett and Melinda Gough laid some background to the intersections between professional performers and academic research that will form the crux of our week here.

Fundamentally these explorations are speculative. Theatre history can sometimes risk giving the impression that scholarship generates evidence, evidence means facts, and facts = This is How Things Were in the Past. Yet recent approaches have sought to underscore how academic understanding of the theatrical past, while necessarily foregrounding questions of evidence, is always necessarily speculative. In seeking to erase the division between performance practices, rehearsal, and scholarship, these workshops are one site in which we can model a shared exploration of text, performance, and history: we’re all imagining the past.

In turn, as we settled into the room, our opening conversations about “Practice as Research” opened up a variety of approaches and prompted some queries about what performers in the room, working with pre-selected scenes, might be aiming to do: are we looking to imagine what decisions might have been made in performance historically? Do we want to see what the text would have looked like on a Renaissance stage? Or are we playing less reverently with texts, prioritising contemporary performance, or thinking about what works best for us here today? Perhaps it’s really about the combination of all of that? Certainly, many emphasised how thinking about historical practices can help inform the present and help to shape the future; something that came up repeatedly is how the period’s performance and casting practices show the past to be far less conservative than many of today’s popular assumptions about the “Renaissance stage” (and thereby less conservative than many practices in twenty-first century classical theatre). By rediscovering elements of past performance and workshopping them, it’s possible we can (re)introduce myriad possibilities for constructive, healthy approaches to gender in performance—and rather than being innovations, those approaches are rooted in a long line of theatrical and cultural histories.

For the haudenosaunee on whose land Stratford, Ontario sits, there were 12 to 15 genders.

Our conversations and introductions made clear that these workshops are invested in a two-way, collaborative exchange between everybody in the room: their forms of expertise, their backgrounds, their identities. We’re joined by academics, actors, and actor-academics. We’re thinking about trans identity and female identity; about race and spirituality; about intersectionality. Dramaturge Gein Wong’s warm-up led us through contemplations about our place in the room, our relationship with the world, and they helped bring to mind the complex histories of Indigenous, knowledge, colonialism, and healing attendant on the very land on which we’re sat. I was particularly grateful for the optimism that characterised this warm-up: Gein spoke of a burgeoning Indigenous Renaissance occurring in and beyond Canada (celebrating, for instance, Jeremy Dutcher’s recent award of the Polaris prize); in the political climate of 2018, this sense of artistic momentum towards more diverse-positive futures are invaluable and urgent.

If the Laboratory were like a hospital, it would be a teaching hospital.

We’re lucky to be joined by Keira Loughran, the Associate Producer who runs the Lab and whose collaboration has made this week possible, and by our Stage Manager for the week, Renate Hanson.

Keira explained the history of Stratford Festival’s Laboratory and how it aligns with many of the aims of a project such as Engendering the Stage. It started out, at the suggestion of Festival director Antoni Cimolino and under Keira’s guidance, through attempts to diversify the canon of classical drama and to change ways of working in rehearsal and towards production. Working with the Festival’s repertory actors on small scenes, topics, or themes relevant to classical drama, they provide the chance to workshop and experiment. In particular, in the early years of the Lab, three central questions emerged: what is it like to be a woman in a classically-motivated company? What is it like to be a diverse actor in a classically-motivated company? What is it like to preserve one’s mental health in a classically-motivated company?

The Lab, in essence, provides the space for artists to be artists and to give time to the voices of performers—to allow questions and experiments in process.

Process not product.

As is central to the Lab, workshops are about process, rehearsal, and experimentation without working towards a final product or production.

This year’s various Lab sessions are designed to think further about how this way of working can be made more central to the Festival as a whole and indeed to the wider Canadian and international theatre industries. For me, Keira’s descriptions of the Lab, the Festival’s amazing work to date, and their ambitions for its future emphasised how closely current concerns in the theatre industry are aligned with current questions of theatre history: whose history is theatre history? What identities do the texts and practices of the past represent or offer? How can different methodologies, working practices, and collaborations help recover erased or forgotten voices, or rediscover historic forms of power or agency—dramatic or extradramatic?

By way of reference to her own directorial experiences working on the Festival’s production of Comedy of Errors this year (about which there’s a dedicated panel dedicated on Monday’s events at McMaster), Keira noted that this year’s Lab fits in with wider trends towards bringing scholarly expertise into rehearsal rooms and closing the gap between performance and scholarship.

She puts off her cloak and draws her sword (The Roaring Girl, 3.1.65.1)

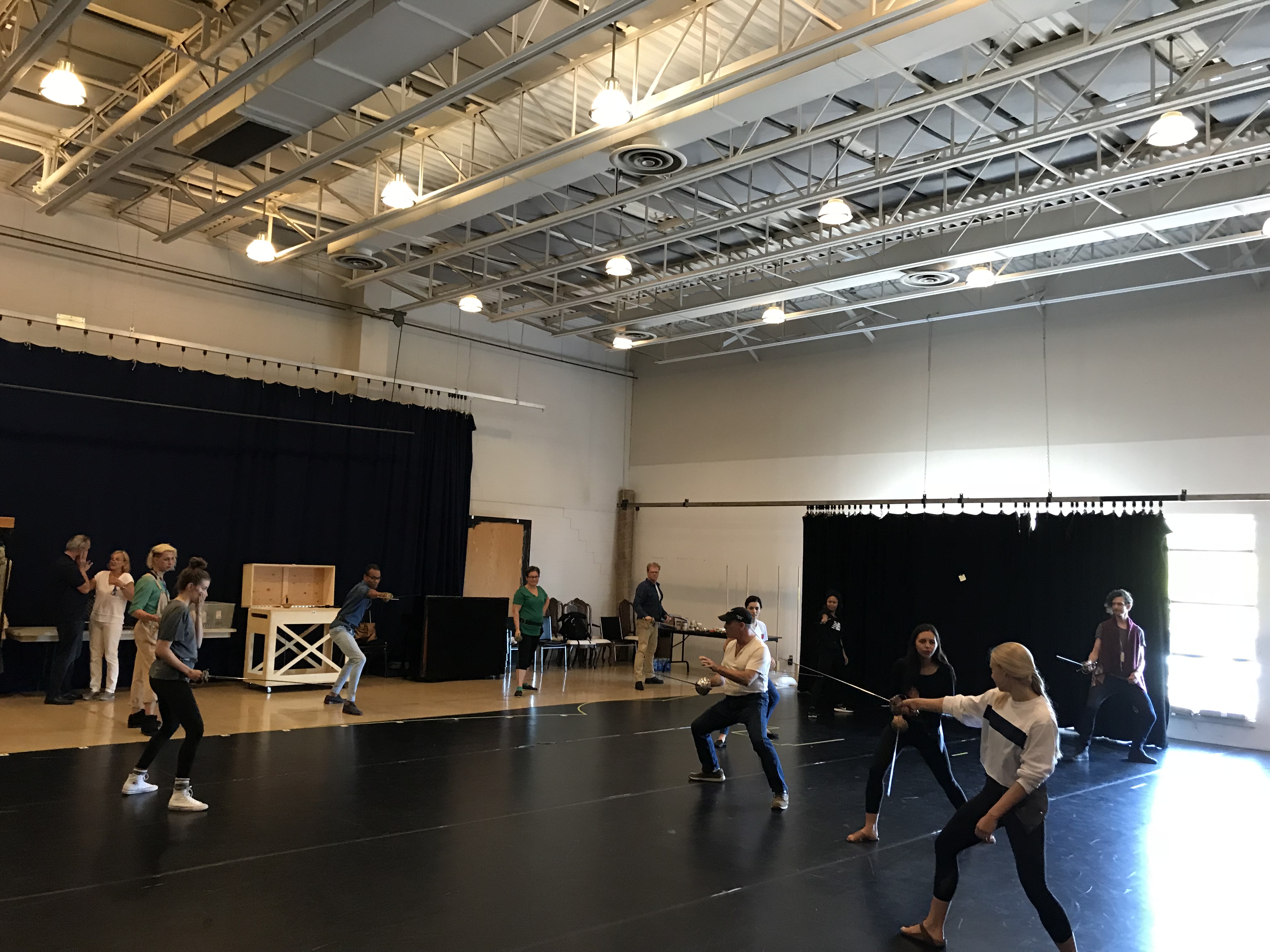

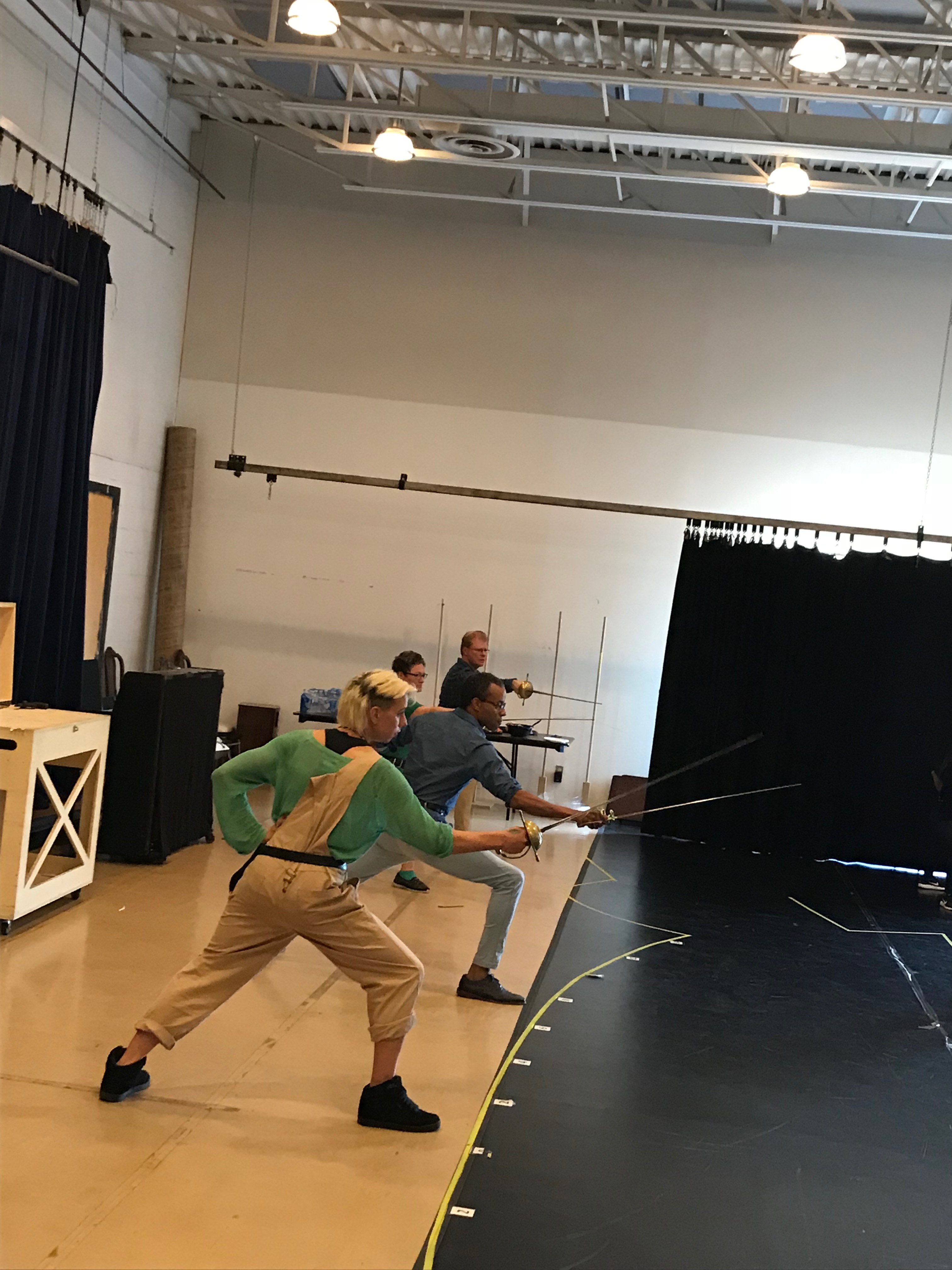

After these discussions, actors and performers drew their swords. After all, all of the scenes being workshopped at the Lab involve elements of swordplay.

The Company’s Fight Captain Wayne Best led a masterclass on how to move with swords, how to draw, how to cut and thrust, to parry, to stand en garde.

The fighting workshop drew attention to how the tiniest details of gesture and movement have major significance—for other actors in a scene as well as for audiences.

When two armed actors move towards one another in a stage space, when do they decide to stop, draw, or simply move more cautiously? If one of them moves with a hand on their sword, is that a sign of martial confidence that may stop you in your tracks earlier? The trails of sheathed swords out of the back of an actor’s body affects the spaces you move through and the way you sit down; in turn, the movement of the draw and the placement of the feet—particularly the grounding of the body for balance and quick movement—call for continual readiness. The ripeness is all.

It affects your whole character, whether you’re good or bad at it.

Pamela Brown mentioned that the presence of so many swords in a large space prompted the question: how would you feel in the middle of so many armed male characters without a sword? Might this be an aspect of stagework that informs the verbal sparring characteristic of innamorata types from Italian commedia (in turn so influential on English and other European performance traditions)—one that affects stance and physical stature?

Numerous other intriguing questions came out of this brief exercise in swordplay that will no doubt resound and mutate throughout the week. Wayne Best pointed (literally) to the close relationship between twenty-first-century health and safety concerns for an actor and the principles of self-defence: at the end of the day, you don’t want to get hurt. These fights are in many ways a combination of historical imagination and material/bodily practicality: the same combination faced by Renaissance actors. I also wondered how such swordplay might work in much smaller spaces or stages. And what difference would Renaissance clothing make (for instance, an historically male-dressed character trailing a sword has to manage a turning circle, but so does a character in a wide skirt)? Might such movements translate to other forms of dramatic exchange, and so might typically unarmed characters be influenced in other ways by the dramaturgy of stage fighting?

This fight workshop raised questions about the relationship between body, stance, gesture, and performance that will be central to questions across the week. As one actor remarked, it crucially affects your physicality and offers an opportunity physically to embody power: they noted that the experience of workshopping these actions in 2018 provides opportunities for an element of powerful or aggressive physicality not normally afforded “traditional” female roles.

Let Shakespeare die.

Before we moved onto a first read-through of our various scenes for the week, Jamie Milay—a multimedia performance artist—treated us to a blistering provocation about Shakespeare, imploring: let him die. Milay urged us to admit, to allow, to provide voices beyond Shakespeare: genderqueer characters and playwrights from the past, contemporary trans voices, postcolonial perspectives, more. Casting, cross-casting, and “all-female” productions are not enough.

This was amazing from @JamieMilay. A spoken word piece that urges: give us anyone else but Shakespeare. A clarion call for diverse voices from across the world, across genders and sexualities, across eras. 🔥 pic.twitter.com/ZefBYOraS6

— Engendering the Stage (@EngenderStage) September 18, 2018

Their poem raised questions about what exactly we’re doing in this room. What about the wider forms of representation that might be occasioned by laying Shakespeare to rest and by admitting a much wider range of voices, parts, and pasts?

The day finished with read throughs of our different scenes for the week.

Here, we’re working from scratch and thinking about the basics of what’s going on in a scene: how it might work, what it might look like, what might specific things mean? It’s a chance to build up and out from exchanges between acting practice, scholarship, history, print, and performance. Indeed, this part of the afternoon’s work cues the beginning of an in-finite research and rehearsal process raising ideas about character and voice that will doubtless echo, develop, reshape over the next few days…