Day 4 was a slightly different day for Engendering the Stage at Stratford Festival Laboratory. Unfortunately, due to unavoidable scheduling, the company actors were not with us on Friday, and so we had a series of talks, shows, and chances for conversation with the remaining participants of the workshops. This meant not only a tour de force about the power, in multiple senses, of early modern theatre from Emma Frankland on her Galatea project but the chance to reflect and learn about ways to move forward—in the academy and in the arts—on and beyond “diversity.” Central to this week’s experience for many of us has been learning about how we can all use different forms of privilege and power to discover more about, work with, and make central the indigenous identities and experiences whose land these buildings occupy. Today’s conversations provided an opportunity to reflect hard on what action on intersectionality might look like in all our various practices.

What is the duty of care for an artist?

Emma spoke brilliantly about her Galatea project, working on John Lyly’s play with a trans and non-binary, BAME, and British Sign Language cast (see some documentation and discussion of this work here).

Shoutout to @andykesson on #Galatea as “the show that Shakespeare never recovered from” #engenderstage #sflab. @elbfrankland being being electrifying as ever on this wonderful play.

— Engendering the Stage (@EngenderStage) September 21, 2018

Wonderful to hear the Hebe speech from #Galatea from @elbfrankland: an extraordinary moment in the middle of the play. “Men will have it so” (see some R&D on this here: https://t.co/ZcS7H9OdXo)

— Engendering the Stage (@EngenderStage) September 21, 2018

Did John Lyly care about the censor? @elbfrankland reminds us that censorship and concern about is not only an early modern concern, referencing trans performances this year. These are pressing quesitons.

— Engendering the Stage (@EngenderStage) September 21, 2018

I really valued this session led by @elbfrankland !! I learned so much and feel so inspired by her work with Gallathea. @EngenderStage #engenderstage pic.twitter.com/svg2TZqHgz

— Sah-Milay (@JamieMilay) September 21, 2018

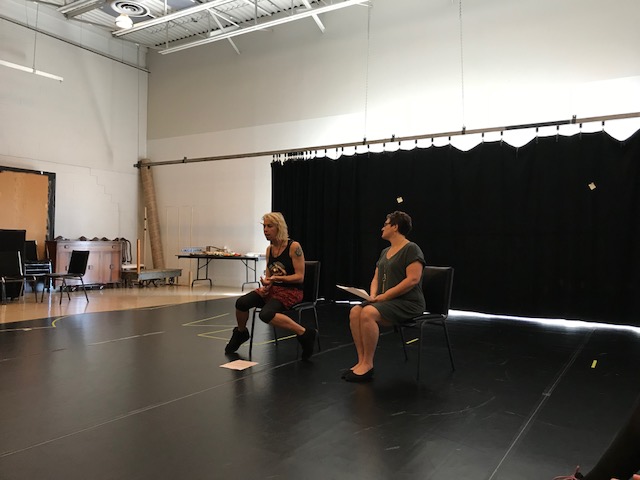

We were lucky to see a scene being workshopped in action with the wonderful Denise Oucharek stepping in cold to explore how the exchange between Phyllida and their father could be played in multiple different ways as part of a trans experience or framework, without reading against the text.

Emma’s work is a flagship model for how texts like Galatea do not need “queering” or “transing”—they don’t require the imposition of a modern framework or analysis onto the play—its queerness and transness are already there.

What would you be curious to see?

Between shows and readings, we had a brief chance to discuss—unfortunately without the presence of the company actors—the model of PaR we’re working with and developing ways in which PaR might be sharpened to work for all invested parties in the future.

Roberta Barker and others stressed that PaR cannot (and is not here) being used to generate answers about the past and answer: this is how things were, this is how it was. Rather, they open up more questions and more avenues of possibility. In a similar vein, Lucy Munro importantly reminded us of the randomness that is at the heart of many moments of discovery and learning in PaR. Whatever structure we’re working with, it’s often serendipity that leads to the most productive and exciting outcomes. We can also look to surrounding relevant bodies of research, and Melinda Gough noted the usefulness of Participatory Action Research (a different PAR) in thinking about how research can be put into reciprocal exchange with different constituencies and communities.

We thought about how the stakes involved in PaR can sometimes shift in favour of academic questions and texts; can we find a way to work that does not privilege the academic impetus, without undermining the importance of what academic historical research brings to the theatrical process (both in and beyond performance-as-research)? It’s also important to recognise the individual working practice of each performer; it can be unhelpful, for instance, to say “do what you want” to an actor trained (as most of us in other industries also are) to work under certain parameters and with certain forms or frames of direction. Returning again to the question central to Day 3, we need to think “what are we here for, what are we doing?”. This is a question that needs to be asked of everybody involved in a given PaR process. On top of all this, I wonder if licence is a useful term for this discussion: to give and be given licence is central. PaR at its best can enable performers to work within a wider set of parameters, skills, tools, and references informed by historical scholarship,and it gives researchers licence to imagine possibilities for the past and generate further questions about what may have been and what may be.

It’s worth reiterating, continually, that the process of this week is the beginning of a long journey in which all stakeholders are discovering new ways of working and new ways of collaborating. This may be generating question upon question, and fostering doubts, but it’s about discovering together a future enriched by all our forms of skill and expertise. This week has been inspiring in pointing to so many ways that such work can be taken forward.

Don’t apologise for your privilege, make it your superpower.

Our conversation on Friday finished by thinking about the most urgent issues at stake in this work. Many of us are used to the language of “diversity,” but Cole Alvis pointed us towards a more productive vocabulary, in which diversity is important in describing a representative plurality in a given room or show, but in which equity is the goal: a structural change, to ensure indigenous, non-white, LGBTQ power and people in institutions themselves, at leadership levels, across the board.

This might not be something achievable through a few weeks of PaR workshops, but it doesn’t mean that it’s not within everybody’s power to work towards this goal by thinking harder and doing more in our own spheres to create institutions that go some way towards this.

We’ve all got to learn to love the paddling

It’s important to end this week by having in mind that the work we’re interested in doing goes far beyond the walls of the studio we’ve been working in. In Emma Frankland’s surfing analogy, it may feel most rewarding to be riding the wave, but that’s just 5% of the sport: we need to learn to love the paddling.

Callan.