We had the chance to speak with Stratford Festival’s Associate Producer Keira Loughran, who organises the Festival’s Forum and Laboratory—a chance to develop new plays and “to experiment with diverse approaches to staging the classics.” Keira reflected with us on our week at the Laboratory, where we were exploring gender and representation in early modern European plays. Here, we discuss Canadian theatre, casting, expanding the canon of “classical” texts, and the process and potential involved in combining academia and theatre practice.

Callan Davies: What practical next steps do you see coming out of our Engendering the Stage workshop?

Keira Loughran: The really obvious one is that I’m really interested in the canon of early modern English plays that are putting these questions out there, and hearing them read, getting a chance to speak to them, giving them to artists who maybe have these questions around gender identity closer to their own experience, and more connected to our community of gender non-binary and trans people, to see if they should be included in our season. They should be part of an accessible canon to us. And that goes too for the Spanish Golden age and everybody’s various expertise with classical work. There is nothing that is stopping us from reading [Spanish Golden age plays] in English now—in languages we can understand—and having them in consideration for future productions, as much as the Shakespearean canon currently is.

It’s also really good to know about the scholarship going on [across the world]—to know about the Before Shakespeare project, for instance. Because we’re a national institution with international impact and scope, so those kinds of partnerships and making use of combining resources is always useful. I feel like Melinda and Peter put together an amazing group of scholars. And our Artistic Director [Antoni Cimolino] goes to London all the time, and has connections and contacts there, and now we have more.

In terms of scholars and artists coming together, it’s something I definitely continue to be curious about and it’s something that has been growing at the Lab. It’s something that’s happened in the past with Shakespeare scholars, but it’s good to meet new people. And it’s also good to see how they respond to being in the room, in the process in that way—but I’ve got to say it’s been really positive, overall, that connection. But it just has to get practised a bit more, so the actors are more comfortable. […] We’re always looking to be able to diversify our canon more… in terms of what we work on, what we consider to be the classical canon.

You need partnerships for people to bring things forward and bring things to your attention, and you also need to be having an eye on who can lead those projects—whether it’s an artist or whether it’s a scholar or whether there’s a synergy between two that can support a production and give it the passion that it needs. So this week has been great for all of that, for making those connections and giving us some time together.

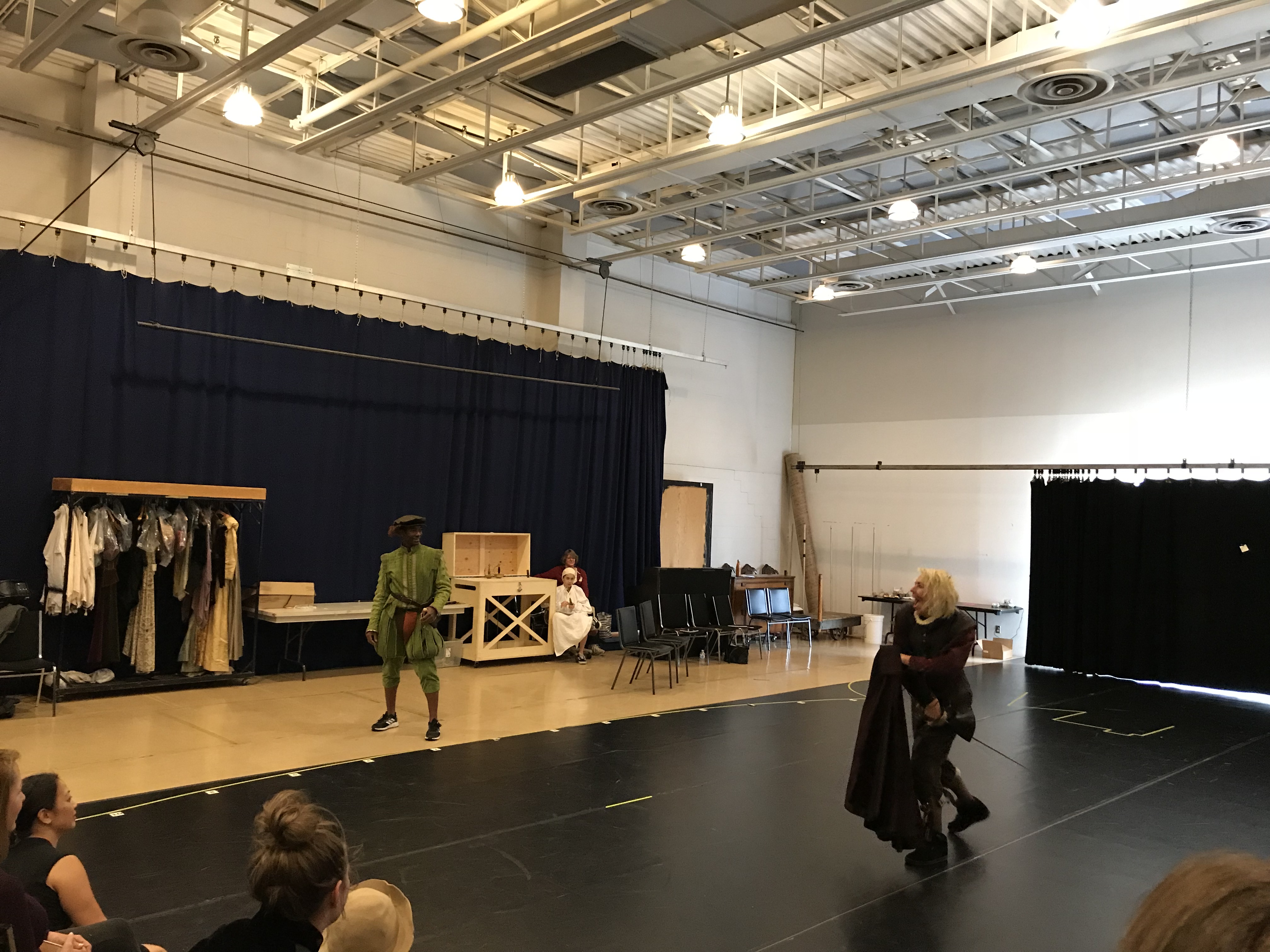

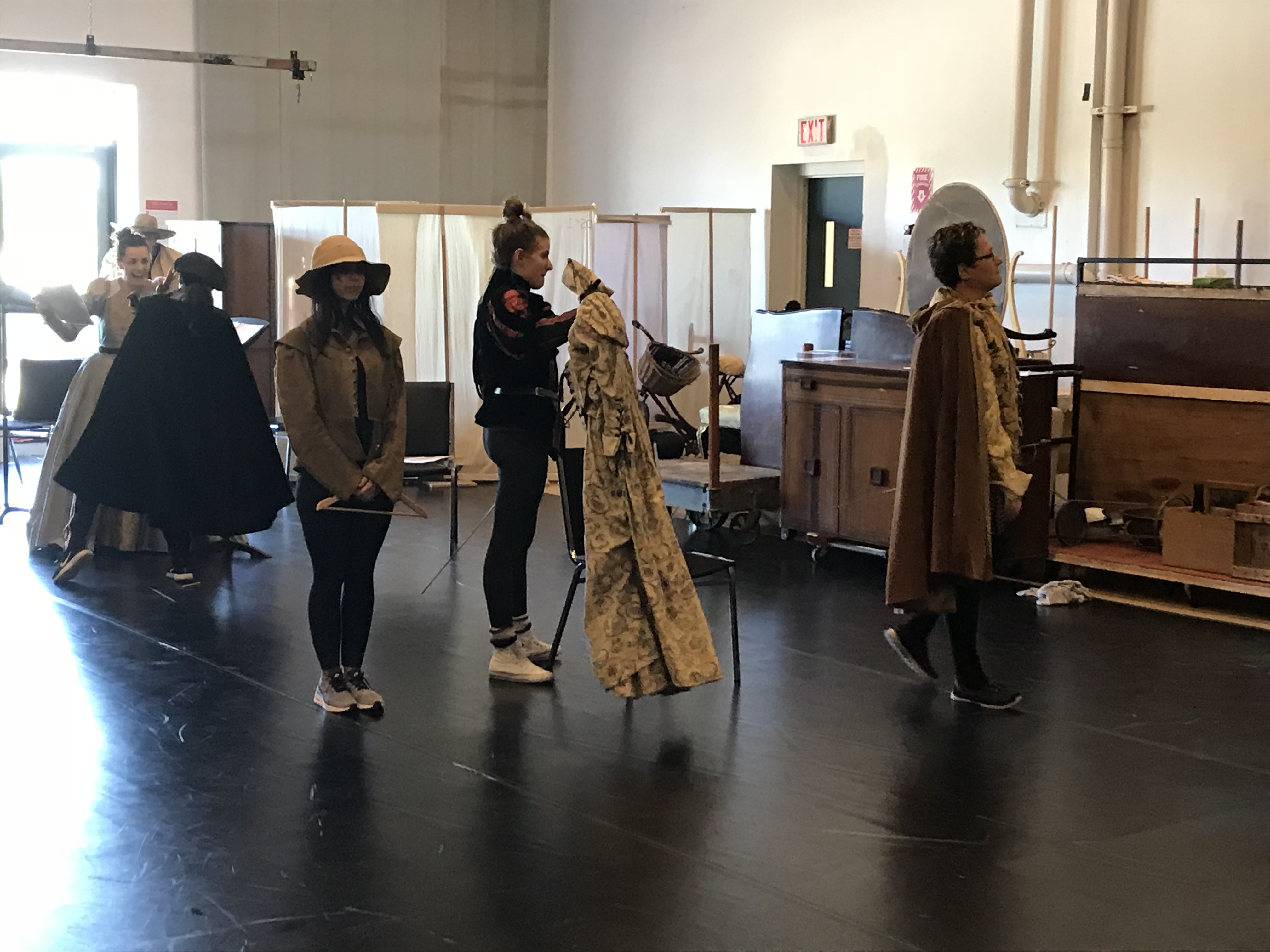

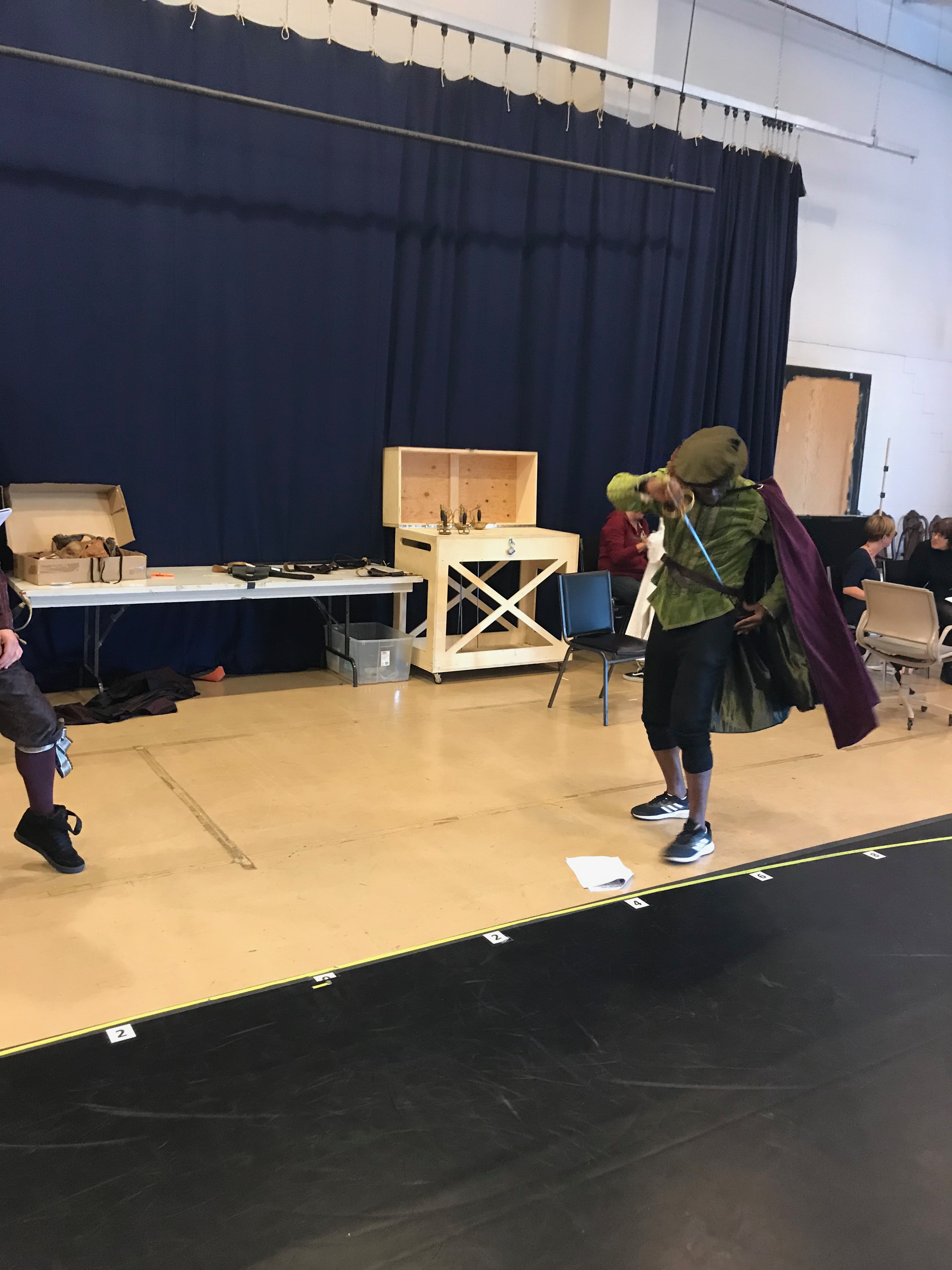

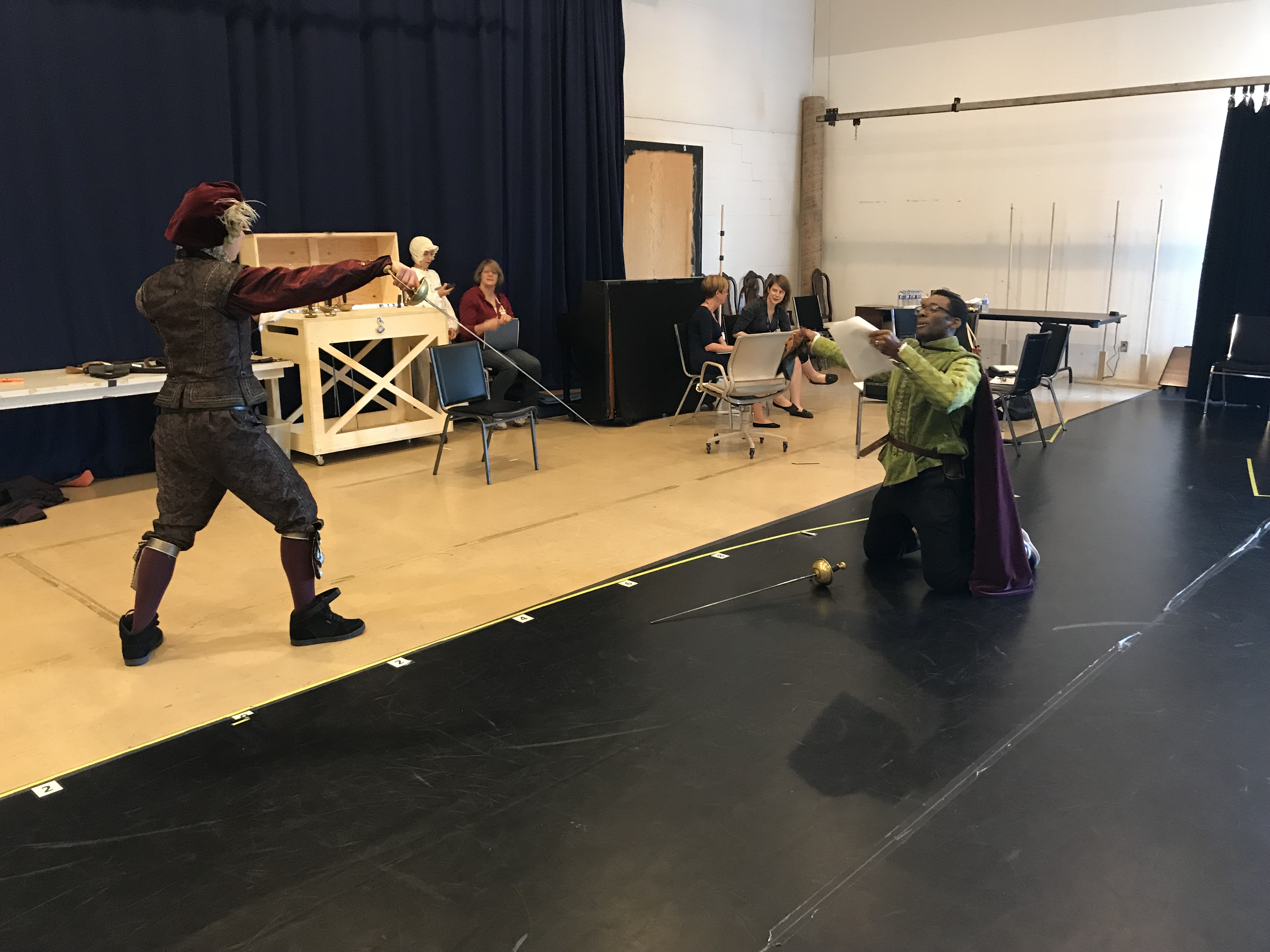

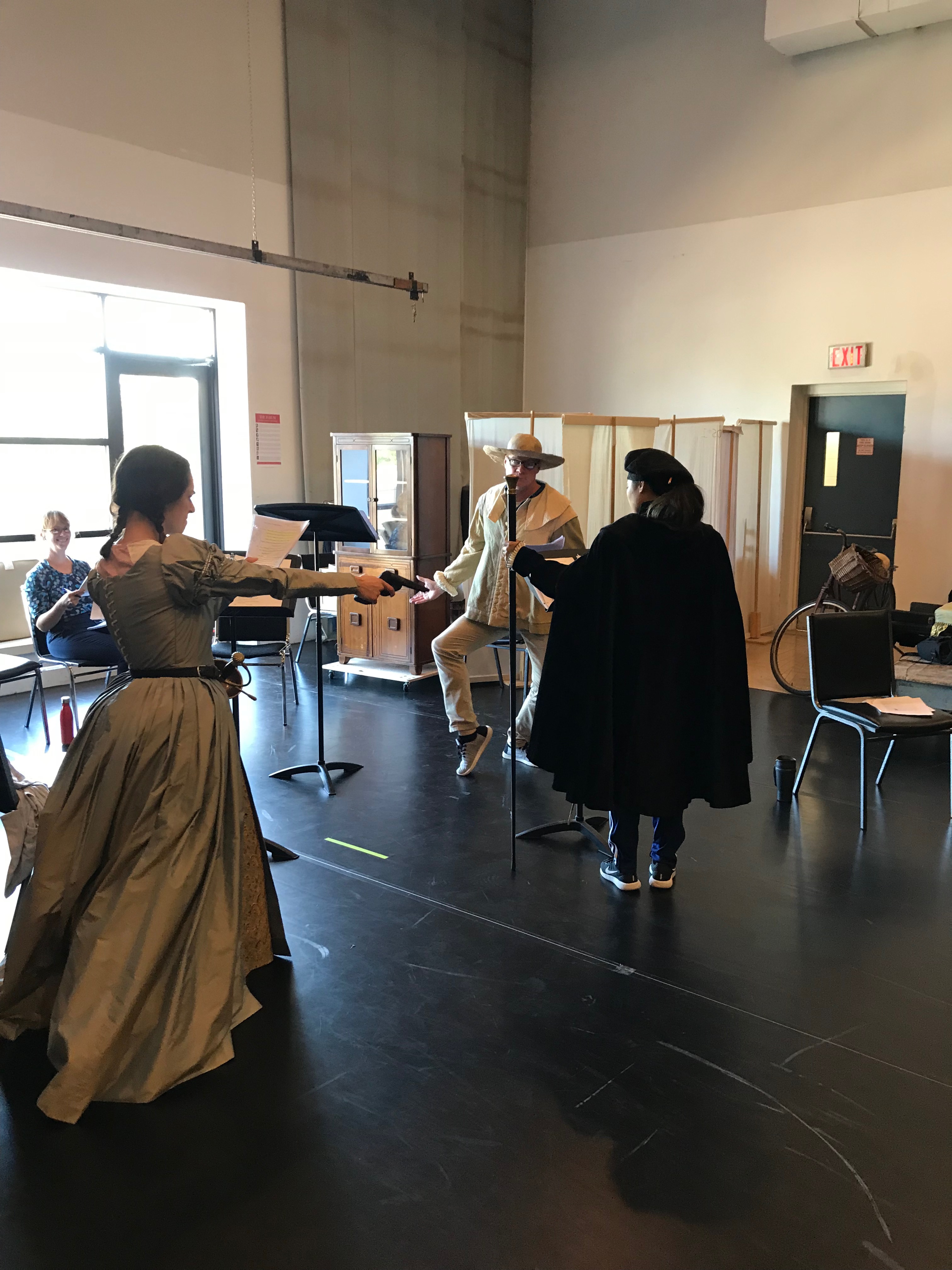

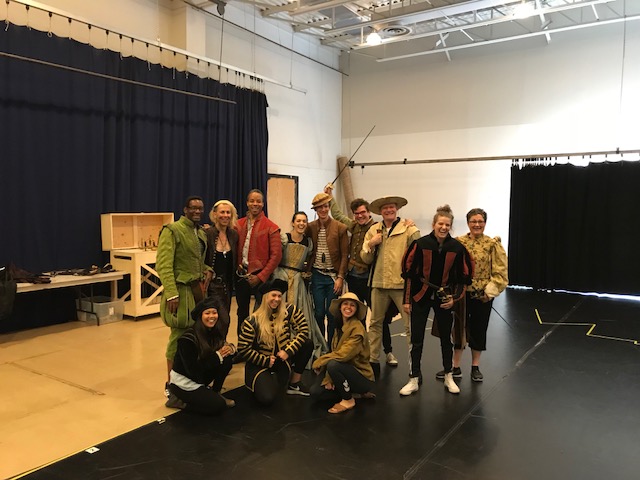

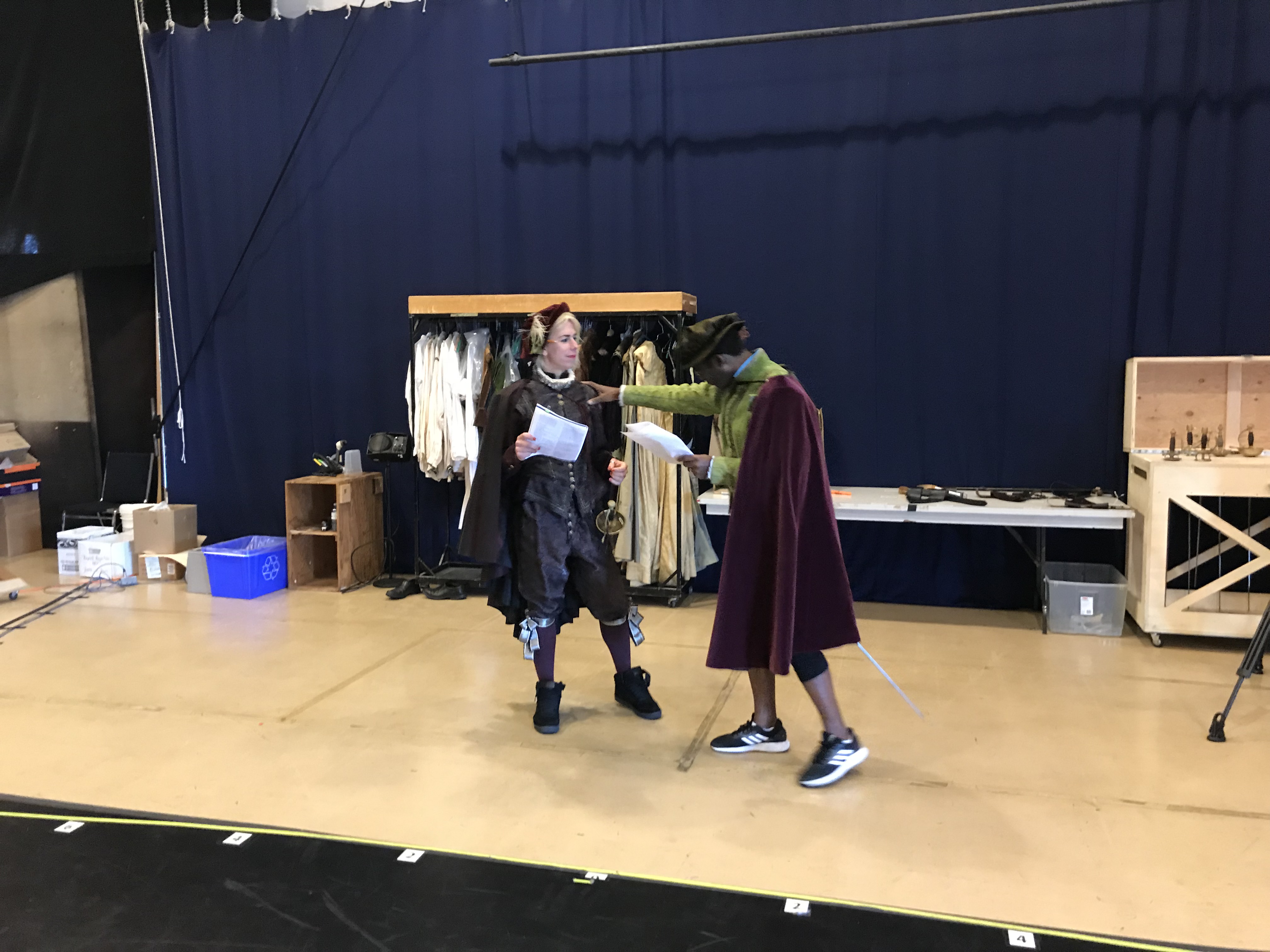

This week we’ve been collaborating on four plays in the workshops (The Roaring Girl, The Maid’s Tragedy, The Lieutenant Nun, Love’s Cure) by combining scholarly research and performer creativity. Sharing the room with academics, performers, directors, and theatremakers has allowed us to bring together historical context and artistic invention. How have you found this method of working in the Lab?

I really enjoy it—particularly for the classical texts, the texts that have specialist scholars working on them. It’s been interesting [this week] for two reasons. One is the expertise that academics bring to the room. [. . .] For me it’s partly been finding out about these plays. I’ve been in the office for ten years now [as Stratford Festival management], and I’ve been in the institution for fifteen years—that’s my Shakespeare knowledge. I know who Beaumont and Fletcher are, I know they collaborated with Shakespeare on some plays…

So to have the chance to see even the excerpts of some of these plays [that we were working with in our workshop in the Lab] is fascinating, because I was a bit more aware of the complexity of the English stage in the Elizabethan period. I’m really curious about the assumptions that we make versus the time to actually consider what was happening—which is what these scholars have spent a lot of their time doing. So I’ve found that exciting as a way to understand these texts and make them more fluid, interpretable, or adaptable to our age and time.

How have you found the focus in the workshops on process rather than product, and on the experience of sharing that creative process with academic researchers?

As an artist and particularly as a director, I question sometimes how art works or how theatre works in our contemporary experience. [. . .] For me, and in my experience here [in Stratford], which is a privileged place (where people sort of like culture, generally!) the more you can share an artistic process—like all art—the more it impacts people’s work and lives in ways that they don’t expect and might not even be able to articulate. When the only thing that people see is a product in a theatre [. . .] I feel that’s very limited: it’s not mining the potential of what art can do. And so opening up process [ie in rehearsal, through documentation and sharing] for me is a really exciting thing.

But it requires a lot of trust and vulnerability on behalf of performers, and it also takes a certain mentality for scholars to bring to the room, to create the space with us. But I think it can be really powerful, and that’s what I’ve felt our workshops so far to be—and that’s great. And I hope, and what I’m curious about, is then how did it impact, what are the unforeseeable impacts of academics being more included in our artistic process? How does that then impact the scholars’ work within their research, or within their editing of dramatic texts, or within the essays they might write. How will their process change because they’ve had the chance to work with us?

Are these questions relevant outside of the Festival to the wider industry?

I believe there is a gap, in Canada at least, between theatre training institutions and universities and practicing theatre companies (one that perhaps doesn’t exist in the States so much, because those scholars are attached to professional companies, whereas in Canada they’re not)… Because of some of the amazing scholars I’ve met, I keep looking for more opportunity to open up process and allow non-artists, or non-professional artists in the room—and seeing how it all lands.

Something you said earlier in the week really struck me. You wondered whether there’s room for a shift in practice in the way that scholarship and the arts—in this case theatre—can work together…

I think that’s true, and you have to be really clear about it. For Comedy [of Errors, Stratford Festival, Apr-Nov. 2018, dir. Keira Loughran], it was my first time doing a Shakespeare at Stratford, so I had these resources of scholarship and doing Shakespeare at my fingertips, which was fantastic. So I did two things: I had a scholar look at my edits [on the text], and I had a couple of scholars to bounce my ideas off of, to call me on it if there were anything that was really missing. And one of the things that I found was exciting was that some of the scholars brought me information that was helpful, and allowed a more fluid interpretation. Their enthusiasm also reinforced that my vision was sound, on an intellectual level. What was also exciting was that my interpretation opened up new possibilities for them in the text; one of the scholars remarked, “Oh, I hadn’t read it like that before!”, so you can discover a text anew. When you have a scholar who’s open-minded like that, that’s an exciting opportunity.

I always say that theatre can transform, and if a scholar can go through that process with the expertise they have, then there’s a degree of authenticity or merit that gives you confidence.

Involving Erin Julian and Kim Solga in my practice—largely in an observing role, although they were the scholars I got to bounce ideas off—that was a bit of a test: how does their presence in the room affect rehearsal. And it was good! They ended up generating an article, which I read to the cast on opening night—because it took me back to the first day of rehearsal. [The article] showed: letting them [the academics] see you made an impact. So, let this audience see you, so it will make an impact [on them].

So, yes, I think it can affect dramatic practice. And I think it’s good for it. I also think it’s good for actors to be more flexible in being in front of an audience… There’s a huge tradition of the privacy and safety of a closed rehearsal hall. And there are absolutely reasons for that. But you also want to see how far you can push or make more common what a safe room is, or what an artistic space is, whether you’re an artist or not. More people who know how to hold that space will be a good thing.

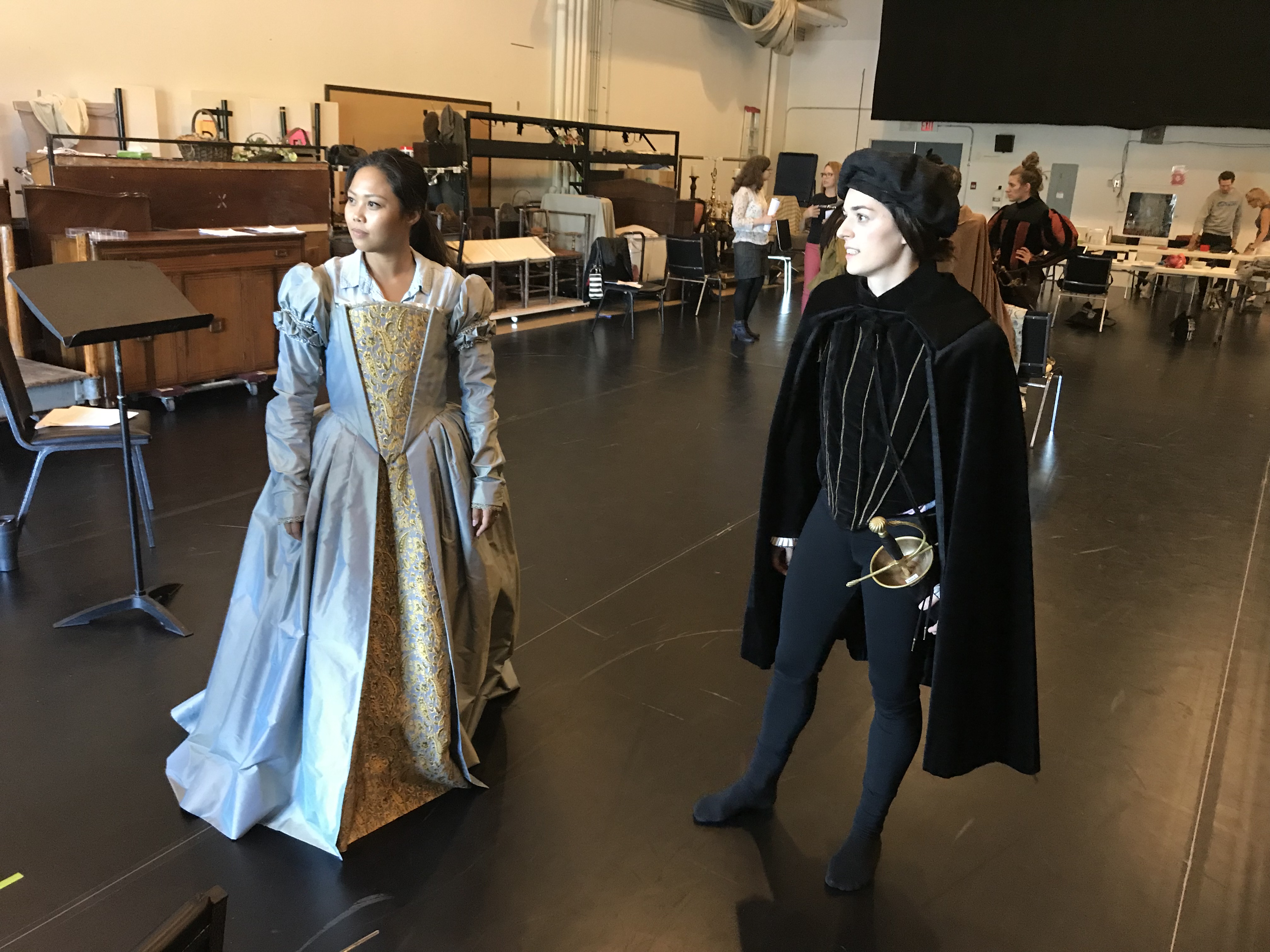

As part of the questions of gender and casting that we’ve been exploring this week, we’ve been thinking a lot about actors bringing themselves to the characters they’re performing. Is this something you see potential in taking forward, coming out of our workshop?

I feel like, in Canada, within a theatre practice context, it’s absolutely necessary if you’re trying to diversify or include more people in the work. I still don’t know how I, as a third-generation, Chinese woman, in Canada, can exist in an Elizabethan context. There were probably Chinese people; I might even be able to find a Chinese person in court somewhere, maybe, but it’s so obscure that if you’re only looking at it from a historical perspective, it’s hard. […] I think there’s a privilege within the social construct of those plays, when they were written—particularly because racialisation was used as a dramatic device, of othering. I acted in all sorts of stuff for a long time, but as I get older and as I get more experienced (and the younger generation is coming to it sooner than I did), if you cannot see yourself, if you can’t feel confident just looking the way you look standing on that stage, then… [. . .] As a director, I feel I get the best work from actors when they can see and find themselves in the work.

Then they can also learn from scholarship of history in ways that are useful: in terms of language, in terms of contexts of language, like what certain things would have meant at the time, in terms of what certain relationships would have meant at the time, so that they can understand that and make a choice in relationship to that. But the other thing is, I feel like if the actors don’t understand the story on a personal level—like how it impacts them as characters and people—then the story won’t be compelling to a modern audience, and then you’re making museum theatre. And I also think there’s things that make you feel like you’re seeing museum theatre that aren’t necessarily helpful (like, period costume?), and I worry about reinforcing tropes in that way.

So it’s a balance of welcoming the scholarship but finding artistic, creative ways to subvert them [the texts] often, and remind people that we’re in a theatre in 2018, in this country, with these people, telling a story for this audience, for these reasons, and I think to do that… you have to acknowledge who you are, and where you are, and allow that to be in the space.

And history and scholarship can give licence to personal and contemporary readings of the text—without them feeling like modern impositions or ahistorical rereadings…

In The Maid’s Tragedy (because I was working on this scene), we tried to make space for our actors to look the way they look in these roles, which made us go: “well, what if we did change the text, what if we did change the play and cast it in this way…? What is the narrative, how can it be changed?” But if these are some of the question of the time, historically—these plays are being written at the same time as The Roaring Girl, and these questions of gender are coming up… Trans people have been around in all cultures from time immemorial… And so if those ideas were present to the writers of those plays, to the actors who animated them, then those people who exist in our society now should be part of telling them again. Which is this “nothing about us without us” catchphrase around inclusivity and inclusion.

And it’s been really interesting too for me this week—I’ve got a lot of these ideas in my head and they’re close to my heart artistically. But the way Emma [Frankland] leads something is going to be different to the way I lead something, because I’m cisgendered and she’s not. And that’s good. That creates diverse practice. [. . . ] An ethical way of practicing that is more based in an acknowledgement of an ensemble of artists coming together is a shift in practice that I’d like to see—and one I think this work demands.

On documentation and dissemination of “process”:

I know why the actors feel the pressure that they feel… We’re all anxious about dissemination of image and dissemination of work that’s not really finished, and what’s professional and what’s not professional. Those are bigger questions that we have to tackle together: what’s process…? There’s massive overhauls that have to happen to fully open all of this up.

On Canadian Theatre Agreement (CTA):

The Canadian Theatre Agreement (CTA), which is the standard agreement between all theatres in English Canada and actors, is culturally bias—if I want to be provocative I argue it’s racist—because it assumes a three-and-a-half-week rehearsal process on a script that exists, that has a maximum two-and-a-half hour running time. You can’t do it otherwise. All of the funding supports that process. If you need something that takes a longer process, you can’t get the funding for it, and if you can’t get the funding for it, you can’t do the work, and if you can’t do the work then nothing changes. So the more you can get universities and places that fund research stretched out to cross boundaries of industries—scholars to actors—then there is a potential pooling of resources, and then maybe you can actually lobby for more flexible rules around these ideas, because people understand them differently in practice. So that’s a form of practice that could change: it’s possible to change it, but it is big!