The skilled boy-actresses of Jacobean England were central to theatrical representation in an era when commercial theatre is often said to be dominated by male performers. But this blog offers new contexts for understanding the boy-actress of Shakespeare, Webster, Jonson and others by contrasting what we can glean about their practice in a specific genre, namely tragedy, against the dynamic, agile, muscular enactment of femininity by women performing ‘feats of activity’, the display of the extraordinarily skilled body. In particular, it deals with the women who danced on the ropes in inn-yards, at court and perhaps also in playhouses.

The King’s Men were chief among the London playing companies of the early seventeenth century, performing at the Globe, court and the Blackfriars, and they are strongly associated with two particular playwrights, Shakespeare and Fletcher. In their first decade, their tragic repertory – from Othello (1602-4) to The Duchess of Malfi (1613) – is packed with feminine corpses, skulls, statues and monuments. Such tropes have long been said to emphasise stasis and present an extreme monumentalisation and spectacular display of the body of the boy-actress who played leading female roles. This observation may be a commonplace in scholarship, but what if these tropes are not simply a default response to patriarchy – not merely what happens to ideas of femininity and the feminine body under patriarchy – but are in fact reactions to other kinds of femininity enacted by other kinds of players, both elsewhere and inside the playhouses?

This blog examines very different ‘feats of activity’, exploring female rope dancers across England and Europe. Though these depictions of femininity by different kinds of player exist on a spectrum of skilled physical labour, the insistent monumentalisation of the King’s Men’s tragic boy-actress suggests that, for this company at least, such an emphasis may in part be an act of emulation and opposition, a shaping of what happens on the commercial stages of the playing companies against other kinds of players.

* * *

For early moderns, rope is a cheap, readily available material from which to create a playing space. Dancing on the rope, women enact a vertiginous femininity, occupying the vertical in a way usually reserved for deities in court masques or indoor playhouse performance. For rope-dancers, the slack rope around which they spin, the tight rope on which they jump and walk, the rope on which they screech down from the tops of towers, with fireworks strapped to their bodies is a productively simple kit that can be speedily set up and broken down.

Like the simple trestle stage with which Italian commedia troupe toured Europe, setting it up and breaking it down when needed, rope offers touring performers a flexible, mobile playing space in partial contrast to the institutionalised, architectural solidity and groundedness of the built or adapted playhouse – though, as Before Shakespeare has shown us, that playhouse is itself contested, often genuinely wobbly and it relied on rope for its construction and workings. Rope is a place of physical spectacle, akin to a ship’s rigging:

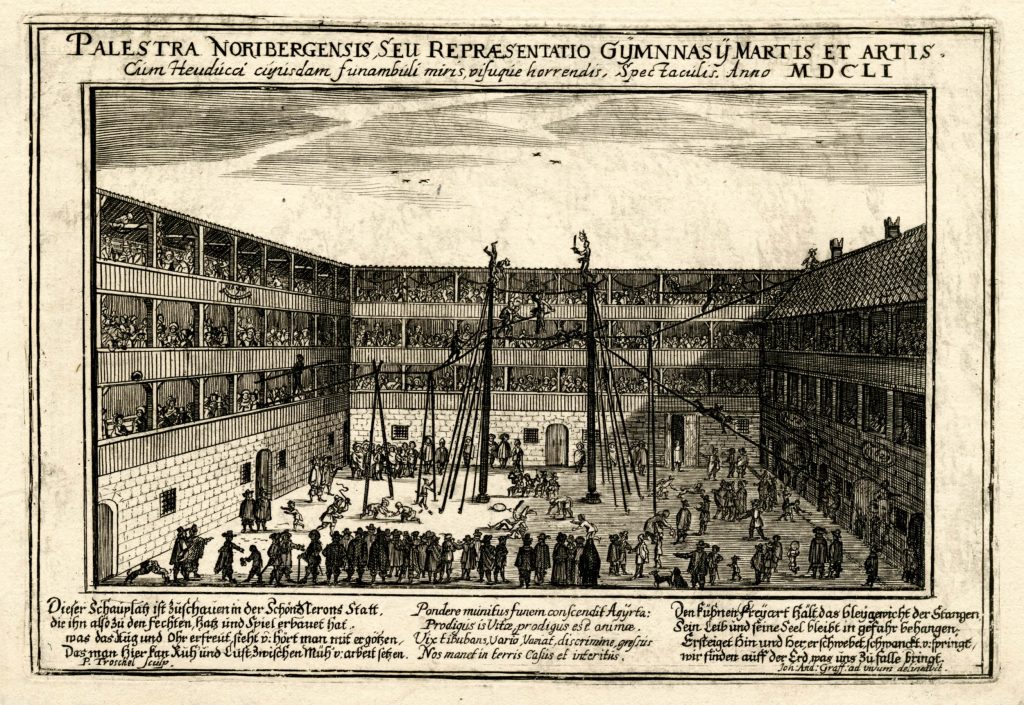

This image of feats of activity and rope-dancing in the fechthaus in Nuremburg from the 1650s makes sense to me of Shakespeare’s Ariel as an aerialist who ‘flamed amazement’ around the wrecked ship. Unlike the trestle stage, however, the rope is attenuated, linear and it has a distinct, crucial trajectory.

The rope fully comes into being as a playing space with the performer’s first step out onto it. This requires not only a crossing, but also – appallingly for those of us with vertigo – a return and a dallying. Stephen Connor writes that

the most characteristic gesture of the wire-walker is, once they have apparently completed their walk, to go back out on the wire . . . the wire-walker aims to occupy rather than merely to penetrate space, . . . to thicken the infinitesimally thin itinerary of the wire into a habitat. . . . . . . . The dallying business of the wire-walker is to insinuate a discourse – from dis-currere, to run back and forth – with the wire.[1]

The dancer’s return transforms the rope from a site of risk alone into a site of play and a suspension of both time and jeopardy. The rope is a stripped down, attenuated performance space activated by what Evelyn Tribble, via Tim Ingold, calls the ‘animacy’ of the gendered rope-dancing body.[2]

Rope-dancing came in several forms. If the rope was slack, cross-dressed women spun and swung around it: a black female fair booth performer from the very early eighteenth century is described as playing

at swing-swang with a rope . . . hanging sometimes by a hand, sometimes by a leg, and sometimes by her toes.[3]

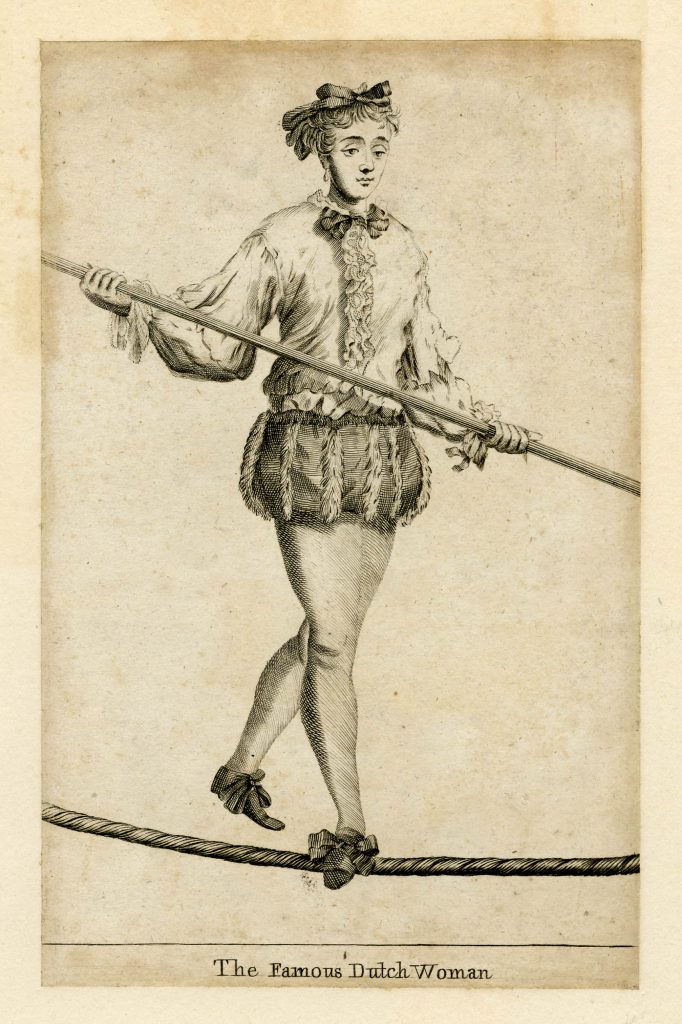

If the rope was tight, women walked, danced and leapt across it, either cross-dressed

or

wearing dresses supported in the vertical axis by corsets, sometimes with brays or breeches beneath. The trope of the leering Jack Pudding or simian pointing grossly up at the woman’s body becomes deeply associated with women’s enactment of this agile, flexible, risky and explosively powerful femininity which is always also an erotic exposure.

Rope-dancing also seemed to be almost everywhere. A Bristol playbill from the early 1630s advertises, alongside a vaulting Irish boy of eight, ‘raredancing on the / Ropes, Acted by his Majesties / servants’ and includes ‘one Mayd / of fifteene years of age, and another / Girl of foure years of age [who] doe dance on / the lowe Rope’ and the younger of the two will go on to ‘turne on the Stage’. John Astington has connected the bill to the troupe led by William Vincent (aka the original Hocus Pocus) and it confidently advertises the presence of these girls – King’s Servants nonetheless and on a ‘stage’.[4]This fits the evidence for the widespread playing of feats of activity inside playhouses, as attested to by R.A. Foakes’ work on the Swan, the Hope contract of 1613 and onwards into the Red Bull during the Commonwealth and Protectorate. So, much as rope-dancing offered cover for stage-plays during the mid-seventeenth century, when plays were effectively outlawed, it could do so not because it came into the playhouses from the cold but precisely because it was already there. Richard Preiss has pointed out that plays were framed and cut across by clowning improvisation, entre-act music or interludes, epilogues and jigs, and he argues that ‘the theatrical program consisted of a medley of interstitial, interactive entertainments’ (9) – this is the play as polyvocal event.[5]In 1636, five years or so after their Bristol performance, Vincent’s troupe is recorded as paying Herbert for a license to perform in the Fortune, so we cannot easily exclude the playhouses from the list of places where the girls of this troupe might have performed.

Another famous troupe of tumblers and rope-dancers, the Peadles, operated for about forty years from the turn of the seventeenth century and was led during the 1630s by Sisley Peadle. Tumbling troupes were organised around familial structures, and tumblers were also recorded as members of playing companies, from the Elizabethan rope-dancers of the ‘Queenes players’ in Bridgnorth in the 1590s to Abraham Peadle at the Fortune in the 1620s as a member of the Palsgrave’s Men. And, as Abraham’s name, the Irish boy in Bristol and the black rope-dancer in Southwark Fair suggest, this performance mode is deeply intertwined with racialised, othered identities, like the 16th-century Turkish rope-walkers in Venice. Marketable personas are also adopted: there are so-called Turkish rope-dancers who adopt the name but no visual signifiers of ‘Turkishness’ and a Turk –called ‘the Albion Blackamoor’ – dancing on the ropes in the Red Bull in the 1650s turns out not to be a Turk at all but a black Londoner. It’s a moment that reads like The Life of Brianand which undermines an early modern racist commonplace by setting it next to neighbourliness, community and familiarity. An ‘old Matron’ watching the Turk dance on the rope declares, ‘Sure, if he be not the Devil, the Devil begot him’; but she elicits this response:

no truly Neighbor, quoth another Woman, I knowhim, as well as a Beggar knows his dish; hee is a Black-fryers Water-man, and his Mother is living on the Bank-side, and as I have often heard her say, Her son learnt this Art, when he was a Sea-boy, only was a little since taught some Pretty Tricks by a Jack-pudding neer Long-Lane.[6]

This account may well simply be part of the mid-century discourse of satire and newsprint and may well not be trustworthy. That said, however, the decision to reframe a seemingly exotic performer by claiming his status as a black Londoner as quotidian and unexceptional is a revealing rhetorical move.

* * *

At this point, it’s probably important to acknowledge that there don’t seem to be any examples of rope-dancing in any pre-Protectorate plays. But if we have to wait for Davenant’s The Cruelty of the Spaniards in Peru(1658) for the first example of rope-dancing in a scripted performance, then rather than seeking the activity in the playtext, its absence instead pushes us to consider how the activity informs playing itself and the practice of the boy-actress in particular. This, like the fragmentation of the performance event inside the playhouse also breaks down the hierarchy of tragic heroine and rope-dancer. It suggests that the latter is not superfluous to or lower than the other; that she is not straining to become the other but may, in fact, be a condition for the other.

How are we to make the move from rope-dancing into canonical drama? One way is to take seriously the performance of bodily skill and the risks that it posed to safety and bodily integrity. The text-free performance of the rope-dancer and the histrionics of the early modern player are connected by the skilful overcoming of risk. The jeopardy of the rope-dancer as she walks, leaps or swings from the tight- or slack-rope italicises the jeopardy involved in every display of acting skill, from Emilia labouring to unpin Desdemona within the duration of the Willow song, to Hermione’s virtuoso control of breath and muscle before her coup de thêatrein The Winter’s Tale(5.3). What’s more, the girl of four who ‘doth turn on the Stage’ in Bristol is a tumbler, a child of bodily turning, whose profession retains its association with other feminine turners. Both Shakespeare’s ‘Triple-turned whore’ Cleopatra (4.12.13) and Fletcher’s Quisara who ‘turns, for millions!’ (3.1.239), are protean but, in defining their hypertheatricality, we might also consider the other side of this performative metaphor, the corporeal act of turning.

* * *

One of the ideological successes of the first decade or so of Jacobean tragedies is the elision of the enskilled, labouring body required for the representation of femininity – crucially, those bodies are those of both the boy-actress andthe female rope-dancer and player. By looking across early modern performance culture, by considering its intersections and its distribution of skills across gender boundaries, we can begin to rethink this. The tragic boy-actress is one representative of early modern femininity, one who over-goes and resists the enactment of femininity as it was done otherwise and elsewhere.

[1]Steven Connor, ‘Man is a Rope’, in Catherine Yass Highwire, writings by Francis McKee, Steven Connor (ArtAngel: Glasgow International Festival of Contemporary Visual Art, 2008), no pagination.

[2]Evelyn Tribble, Early Modern Actors and Shakespeare’s Theatre: Thinking with the Body (London: Bloomsbury, Arden Shakespeare, 2017), p. 24.

[3]Edward Ward, The London Spy (4thedition, 1709), p. 185.

[4]John Astington, ‘Trade, taverns, and Touring Players in Seventeenth-Century Bristol’, Theatre Notebook 71:3 (2017), 161-168.

[5]Richard Preiss, Clowning and Authorship in Early Modern Theatre (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 9.

[6]Mercurius Fumigosus (30 August-6 September, 1654), p. 126.