When the first lockdown was announced in the UK in March 2020, the ETS team was forced to urgently confront questions connected to archival access. Questions about who has been left out of early modern archives, how and why were already built into our project but became much more pressing. With these issues came broader questions of how we might rebuild inclusive archives and libraries after the pandemic – both ones used by scholars and more generally.

We decided to reflect on our pandemic experience in conversation with other archival projects, to share resources and solutions to some of the obstacles that the pandemic created, and to think about the social and cultural roles that libraries and archives play in research, learning, and community building.

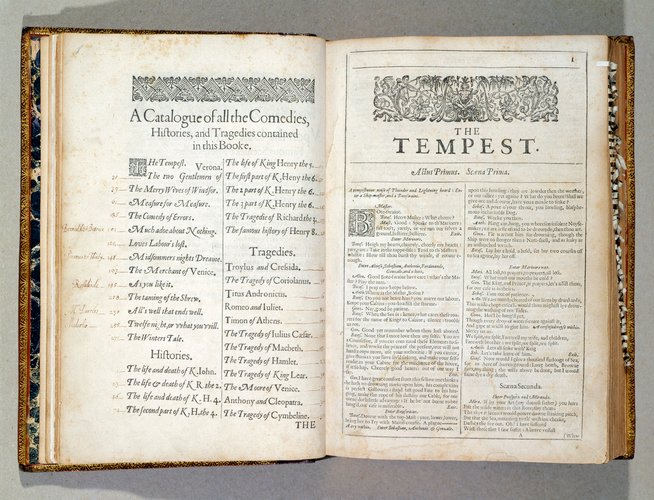

Our first interview is with members of the AHRC-funded project, Shakespeare in the Royal Collection. We spoke with Prof Gordon McMullan (King’s College London), Prof Kate Retford (Birkbeck, University of London), and Dr Sally Barnden (King’s College London). The Royal Librarian approached McMullan early in 2016 to ask if he might include the Royal Collection Trust’s exhibition of Shakespeare-related items from the Royal Collection in the publicity for the Shakespeare400 season (which was led by King’s in partnership with twenty-five major London cultural organizations). In due course, this led McMullan and Barnden (the latter employed for six months by King’s to scope the project) to investigate the Shakespeare-related holdings of the Royal Library, which were for the most part acquired from the 18th century onwards (after a period of dissolution following the death of Charles 1). In McMullan’s words, the project explores “the mutual value that Shakespeare the cultural phenomenon and the Royal Family have had for each other over time”, a relationship which “begins with the accession of the George I”.

McMullan is PI and Retford Co-I, and Barnden and Dr Kirsten Tambling are the project’s postdoctoral fellows who, until Covid closures hit, were working in the Library and Archives at Windsor Castle. The project is both literary and art historical, with McMullan and Barnden (broadly) handling literary historical matters and Retford and Tambling the art history side of things.

The project is hosting an online conference from 17-19 June 2021. Other outputs include a website providing comprehensive details of the RCT’s Shakespeare holdings; a digital exhibition; a set of 3D digital visualizations of three spaces in Windsor castle in which Shakespeare performances have taken place, created by Martin Blazeby in collaboration with Noho, with Globe actors providing voiceovers. Parts of these visualizations will be available to Windsor Castle to use in their visitor experience facilities. The ShaRC team will also release an image- and object-focused collection of essays, developed from the exhibit, of interest to academic and general readerly audiences.

We present an edited transcript of our conversation in two parts. Part 1 discusses Covid-related lockdown closures and questions of archival access. Part 2 will include our conversation on the advantages and limits of the “digital archive”

WORKING IN LOCKDOWN, ADAPTING TO COVID

Erin Julian: We started this interview series as a way of reflecting on the obstacles to archival work during Covid. Can you tell us a bit about what’s happened to you in the past year?

Sally Barnden: Sure. Our project team is located mostly in London, but the vast majority of the material that we’re working with is at Windsor Castle. The Royal Archives themselves were mostly closed last February for cataloguing and inventory reasons. They briefly reopened during the period when we were on strike [the UCU strikes in February and March 2020], and then Covid hit, and Windsor Castle as a whole had to close. So there was a sort of preamble to the pandemic, as far as Windsor Castle was concerned. We were also making quite a lot of use of other archives: the National Art Library at the V&A, the British Library, and the National Archives. So general archival closures were a problem.

I suppose we were lucky insofar as all of these problems started when we were already 18 months into the project, so we had quite a significant archival base, a backlog to work with.

The Royal Archives’ peculiarities shaped our work here. They have very strict rules: you can’t take photographs, as you can these days in most archives, so we probably had taken more thorough notes than we would have done otherwise. So that was kind of a blessing and a curse insofar as we were probably already expecting that it wouldn’t be easy to just pop back in and check things – but also we didn’t have a vast library of archival photographs to refer back to.

Gordon McMullan: We were very, very fortunate that the timing meant that Sally and Kirsten had done the vast bulk of the archival work that was absolutely essential. I mean we originally budgeted to go to Sandringham and Balmoral and various other places to see what was there, and none of that has happened because visits haven’t been feasible.

It turns out, happily, that as far as we know there aren’t in fact major objects there that we absolutely must see, as it were.

POSITIVES OF ARCHIVAL CLOSURES?

SB: This is probably something we would have had to do anyway, but I think Covid moved forward the point where we had to let go of the idea of completely exhaustive coverage of every possible Shakespeare-related thing in the Royal Collection and Royal Archives. That we had to come to a point where we decided that these are our 2000 objects and we’re going to say as many interesting things as we can about them rather than go on reading a million letters in the hope that somebody in passing quotes The Merchant of Venice in a historically interesting way. Becoming aware of our limits early last year rather than later was probably quite useful in the long run.

PUBLIC ACCESS AND THE ROYAL COLLECTION

GM: One of the issues we’ve had throughout – which has nothing to do with Covid – is that these buildings are not places where you can go and have a rummage around and see what you can find. The challenge that Sally and Kirsten have had to deal with throughout has been always being asked by an archivist, “What would you like to see and I’ll go and get it?” And, of course, the truthful answer to that is “I’d like to have a rummage in that cupboard, please!” But you’re not allowed to do that. So that has made it much less likely that we would find something startlingly undiscovered because you can’t ask: “Let me see the thing that nobody knows exists yet.” So Sally and Kirsten have been assiduously seeing what we could get to there.

SB: It’s worth mentioning the Georgian Papers programme (https://gpp.rct.uk/) have helped to cover for the fact that we haven’t had access to so many of these documents. The fact that the Royal Collection Trust had this vast digitization project, which was already well underway, has been really useful. Also the fact that that the Georgian Papers team were engaging with the Royal Archives as a whole meant that there were lists of the kinds of documents that existed, so we were able to slightly break that pattern of the archivist saying “what do you want to see?” and us saying, “well, we don’t know, have you got any of this? No. Have you got any of this? No.” And we were able to go through them slightly more systematically, which did help.

Lucy Munro: Have the Windsor archives actually opened at all since the pandemic began?

SB: No. They closed for Covid, I guess, early March last year, and they haven’t reopened at all. The staff have had access. I think in the first UK lockdown there were very few staff on site at all, and then, more recently, the library and print room staff have been in one day a week, something like that. There have been some staff in the archives, so it’s been possible to check some queries and things.

GM: It’s also worth adding that the Royal Archives and Windsor Castle derive their income from tourists visiting the Castle, which means that during Covid their activities and staffing have necessarily been reduced because they haven’t had the normal income stream from visitors. This has meant that the handful of curators that have been engaged in our project are in fact doing more work to help us than we had anticipated. The senior curators have been photocopying things for us, taking pictures of things for us – which is immensely kind of them!

SB: We’ve been quite lucky in terms of the Royal Collection curators making themselves available by email and by Zoom and putting in a huge number of hours with the objects that we otherwise would have hoped to examine ourselves. We’ve been relying very heavily on impressions of these prints or copies of these books that are in other libraries, where they have been digitized – and obviously that leads to some omissions and misunderstandings. So curators have had to go in and say, “oh no actually this print does have lettering” or “actually our copy has an inscription on the flyleaf that you haven’t mentioned, because you haven’t seen our copy”. It’s been very weird doing this kind of object-based research at so many removes from the objects that were interested in. We’re very grateful to the curators who are doing that work for us right now.

GM: We are also very, very aware of our good fortune in having an AHRC grant and thus being publicly funded for this project, because the Georgian Papers project, for instance, didn’t have that public funding – they had a combination of funding from the States and the Royal Household – and when Covid and lockdown began they weren’t in a position to sustain the formal relationship, whereas RCT has been able to carry on working with us because the funding was public and thus external. So we’ve been very, very fortunate in that respect.

The first half of our conversation ends here. In the second half of our interview, coming soon, the ShaRC team tells us more about working under Covid conditions, how they adapted their planned exhibition to a digital format, and the advantages and limits of the “digital archive”.