This blog is the second part of Engendering the Stage’s interview with Shakespeare in the Royal Collection (ShaRC). In Part 1 we discussed questions about lockdown closures and archival access. In part 2 we discuss the merits of the “digital archive”.

THE LIMITS OF THE DIGITAL

Lucy Munro: You mentioned earlier that you’ve had to change plans around other parts of the projects and that the exhibition that was planned to be a physical exhibition has moved online. Could you tell us a bit more about that?

Sally Barnden: We were at the point of estimating loan requests when the pandemic began and it became apparent, for various reasons, that a physical exhibition just wasn’t going to happen. We had quite a detailed account of what we wanted to be in that exhibition and how it would be structured and what the rationale was for all of those objects. So then we reconceived it for an online space. Which has various effects – one of which was that, when we were thinking beyond the Royal Collection about what objects we might want to contextualize, we were suddenly able to be a lot more ambitious, because the costs of packing up a big painting, shipping it to a location, and insuring it, were no longer a factor. We’re now able to think in terms of contextualizing things with paintings, rather than with small prints after paintings, and that kind of thing.

But it does also change the way that the narrative of the exhibition works, because if you imagine these things in a space, then things like scale and colour have a lot more impact on how the different parts of the exhibition impact the viewer. We were going to have this exhibition which would have a few very big oil paintings and some very small things that we think are very interesting, but maybe were at risk of getting lost in a room. We can now make those objects equal size – for better and worse because you lose the sense of scale, but you can also make the smaller things pop a little more.

LM: Your project – of all the projects we’re talking to – has the most art-historical aspects to it. We’re dealing with archival materials, and we’re interested in the physical objects, but the outputs of the project won’t depend on them in quite the same ways as maybe they will in your project. I wondered whether there was anything else to say about that – the problems of going virtual when you have intellectual investments in the ‘thing’ itself?

SB: I can say it’s certainly been an issue on the cataloguing side because one of our main outputs is a website, which will be effectively a database of all the objects. I mention things like inscriptions and describing bindings but scale is lost when you’re describing everything in a virtual realm, both in the exhibition where it will now seem like a three-metre-high painting and three-inch-high photograph are equivalent objects in some way and while we are asking for dimensions of everything, a small bit of text that says “this is three centimetres high” doesn’t really register in the same way that it would, if you were actually in the same space as the objects.

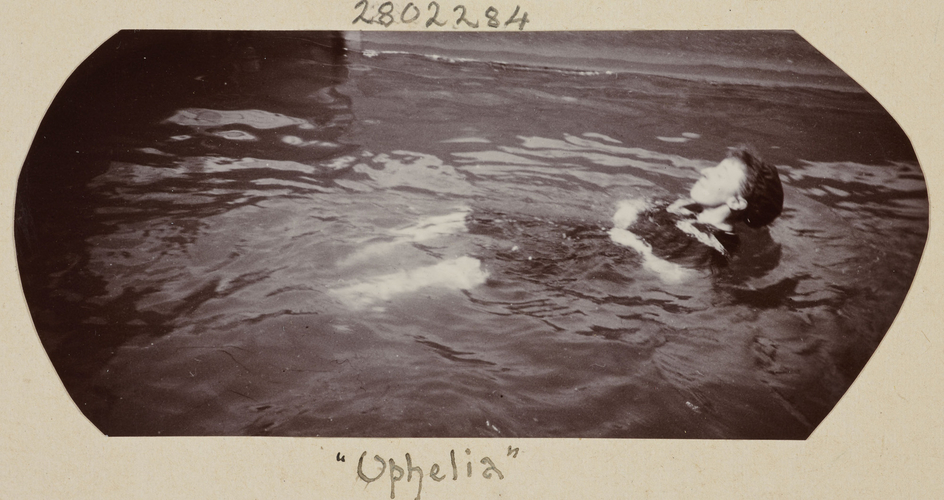

Kate Retford: Yeah. We’ve got that photograph of Princess Helena Victoria as Ophelia.

SB: She was Queen Victoria’s granddaughter.

KR: I remember when we saw that in the archive and we knew intellectually it was tiny. But the scale of it only really hits you when you see it in person, and that is a real shame for the project, particularly for the exhibition, because, you know we’re losing a lot about the materiality and the individuality of the objects. It’s a particular shame because it’s such an incredibly diverse body of material. I’ve not worked on anything which has such engagement with, you know, print, dec[orative] arts, painting, architecture, sculpture, and what we like to call “chod”! There’s so much to say about material and scale and hierarchies of genre, media. And I think we’re having a particular struggle with the digital exhibition because you know the [web design] company want to have neat identical little square views onto objects before you then click through and I’m saying “no, you’ve got see the whole object straight off.” And then we’ve had discussions about “is there any way we can give people a sense of relative scale? Because they’re going to think this miniature’s the same size as this full-length painting.” And there are various ways you can try and communicate that but none of them are great really. So that, I think, is a particularly big challenge.

Gordon McMullan: Another fundamental difference is that when we were going to have an exhibition at the Globe, we knew we’d have a captive audience of about half a million people who were going to come to the Globe in the course of the three months that the show would have been on. Anyone doing a Globe tour would be offered, for an extra quid or something, the chance to have a look at the exhibition. A proportion of them would have done that, and then we would have got our impact* feedback from those people. Well, it’s a touch more tricky when it’s an online exhibition and zero additional funding to market it!

KR: One of the things that was going to be great about the Globe was that a lot of people would have seen the exhibition who would never have gone to see an exhibition of that sort, normally. So we would have had greater impact. The danger with the online exhibition is that the people who look at it will be the people who think “oh, Shakespeare!” The Globe is so much more on the tourist trail that I think we would have got sort of more surprising reactions from people.

GM: That was always the hope – that we would have audiences who wouldn’t naturally go to a royal palace or a royal exhibition coming to see it anyway.

KR: And it would have been global.

Clare McManus: That’s really interesting, because we’re keen to find out how the pandemic has affected archive projects in terms of questions of access. Not only how we get into things but also in terms of bringing things out of the archives for other people. The universal panacea is often seen as digitization, but your experience is saying something different. It can actually be harder to gather a new, more diverse, and inclusive audience for the kind of things you want to show in the virtual environment. [But] if you have a building that’s already associated with some kind of openness towards Shakespeare and some kind of global audience . . .

GM: Yeah, the Globe exhibition wouldn’t have required anyone deliberately going to see it: they would have just kind of wandered through it while coming to visit the Globe, so it didn’t require any marketing in that sense; it was just “well, while you’re here, why don’t look at this?” So we’re frustrated to have lost that opportunity to reach a really broad audience.

THE ADVANTAGES OF THE DIGITAL

GM: But one particular advantage of the digital exhibition is that it will show objects, most of which are not on public display. Scholars can request to go into the Royal library and see things as long as they’re working on an appropriate project and go through all the security clearances, but the items are not generally visible. It was very much a part of our application to the AHRC that we were seeking to democratize one aspect of this immense collection and to make the holdings more generally visible. The more we show the world the materials that they have, the more subsequent scholars, whether in Shakespeare, whether in art history, will know that those things are there and ask to go and look at them. We don’t think Covid has got in the way of that particular aspiration.

And, of course, the digital exhibition has one advantage over a physical exhibition: it doesn’t conk out after three months. However, we will find out how current such a thing can remain beyond the usual three-month lifespan of an exhibition because it may or it may not.

I think there’s a lot to be learned from it when it comes to impact. There is a diminution when you don’t have, as it were, the real thing, but in terms of, for example, school materials, having the online exhibition available for anyone to look at if they’re doing an EPQ† or whatever – so there are gains. But it’s interesting that we won’t quite be able to quantify the gains until long after the project is over. [And p]rojects with digital outputs will require longevity of impact data acquisition, which is not catered for by the duration of a funded project with a fixed end date.

Erin Julian: There’s been a lot of conversation recently about what hybrid conferences, events, performances might look like in the future. It seems to me that your project raises particular challenges to hybrid work. Has the project team been thinking about what your work would look like in this new, post-Covid world?

SB: In terms of hybridity between sort of real-world experiences and digital experiences, Gordon mentioned one of our outputs, which is these 3D interactive visualizations of spaces at Windsor castle. And we were certainly envisioning those when we started as something which would allow you to interact with these spaces in a different way when you were in the space. So we were imagining that hybridity, if you like, between experiencing the space live and experiencing it digitally and that you would be able to think about that overlay between the room as it is now and the room, as it was in the 19th century and how the spatial politics of that room worked for Shakespeare performances. And then because of the huge interest in 3D visualizations and virtual versions of real spaces that’s happened as a result of the pandemic, people will respond differently to those properties and probably more of them will be experiencing them exclusively as virtual properties. We’ll have to think about how that changes what we, what sort of packaging, we need to give them, what textual guides and introductions are necessary when you’re thinking about those spaces as spaces that you’re experiencing exclusively virtually rather than as a comparison with a real space.

KR: Over the last year everyone’s got much more used to online, and I think people’s dexterity, say, with our visualizations is going to be better because everyone’s spent all year looking at and manipulating things online and [paying attention to] which gallery has got the best whizzy digitized version of its collection so, on the one hand, that facilitates that and on the other hand, I worry that it won’t be quite as distinctive as it would have been? So, and I hadn’t really thought about that, actually, before this this conversation, that that’s a real pro and con side to all this.

CMcM: Brilliant. This is all the time we have. Let’s see what Zoom auto transcription does to our conversation!

Notes

*impact under the UK’s Research Excellence Framework, refers to how research affects, changes, or benefits society outside of academia.

†EPQ within the UK’s education system, an additional piece of research that students can undertake alongside their A levels – qualifications taken in the last year of secondary school – for additional credit