Before Charlie Josephine’s I, Joan even opened at Shakespeare’s Globe this summer, it provoked reactions from critics and commentators for its presentation of Joan of Arc as non-binary. Despite the historical record of Joan’s gender identity being inconclusive at best, many were surprised and challenged by the invitation to consider Joan as ‘they’ – as someone whose identity corresponded to neither male nor female, and whose dress and appearance shifted across the gender spectrum in response to their developing self-knowledge. Those who rejected this invitation, who sought to impose a particular label on Joan in the name of ‘historical accuracy’, queried how ‘modern’ ideas of non-binary identity could be used in a play set in fifteenth-century France.

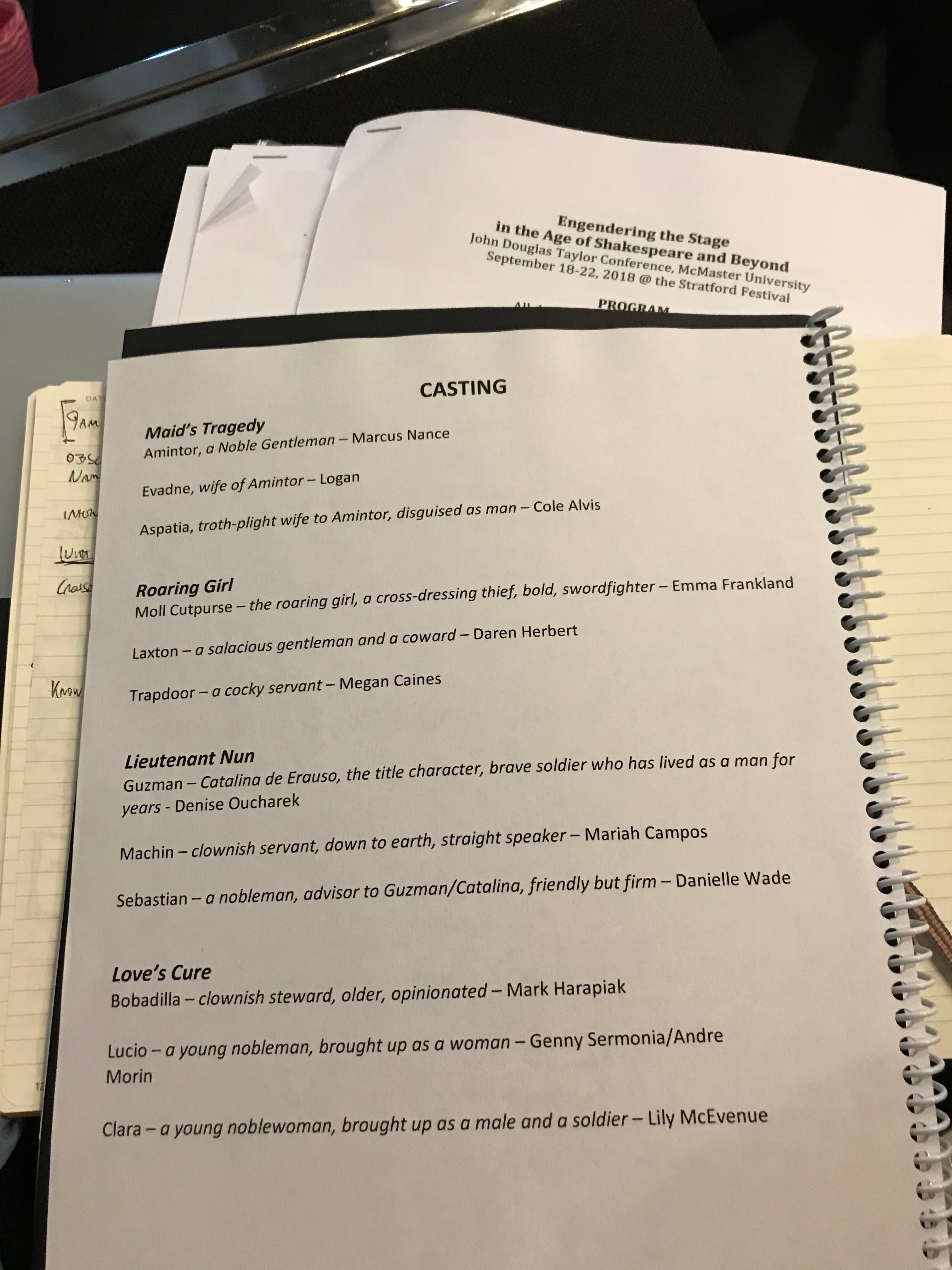

It was precisely this kind of question that the Diverse Shakespeare training sessions discussed with the brilliant volunteers and education practitioners of Shakespeare’s Globe. We spent some time learning more about the diverse and varied performers and performances of the early modern era, ranging from the well-known Moll Cutpurse to unnamed ‘Mayd’ and ‘Girl’ rope-dancers, before talking about how we might incorporate this into our public-facing work. We hoped that this knowledge would help the Globe in their ongoing anti-racist work to challenge white, Euro-centric, cis, and able-bodied views about the diversity of the period in which Shakespeare lived and worked.

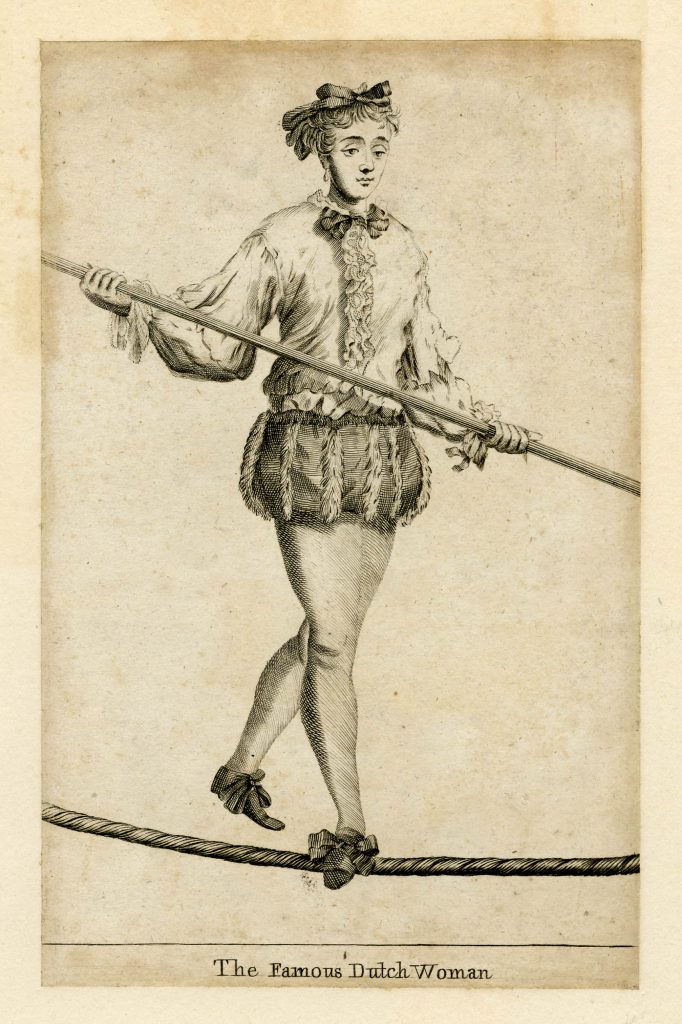

As I planned this session, I found much of my own preconceptions and understandings of the period being challenged. I knew there were people of colour living and working in early modern London; I didn’t know that some families were engaged in the silk trade, or that others were baptised in their parish churches as babies. I knew that women performed in a variety of spaces; I didn’t know that women danced on ropes at the same playhouses that staged Shakespeare and other canonical playwrights’ written drama. I knew there were disabled people living and working in early modern England; I didn’t know that a blind musician performed in Carlisle or that a female acrobat with a limb difference performed in Norwich.

The first challenge I faced was to decide which examples of performers to include: we only had ninety minutes to discuss the exciting diversity of early modern England and its performance industry and, as you will discover, so much to talk about. Most of these examples have been drawn from the Records of Early English Drama project (https://ereed.library.utoronto.ca/), and therefore are already catalogued, digitized, or otherwise organized by archivists and historians.

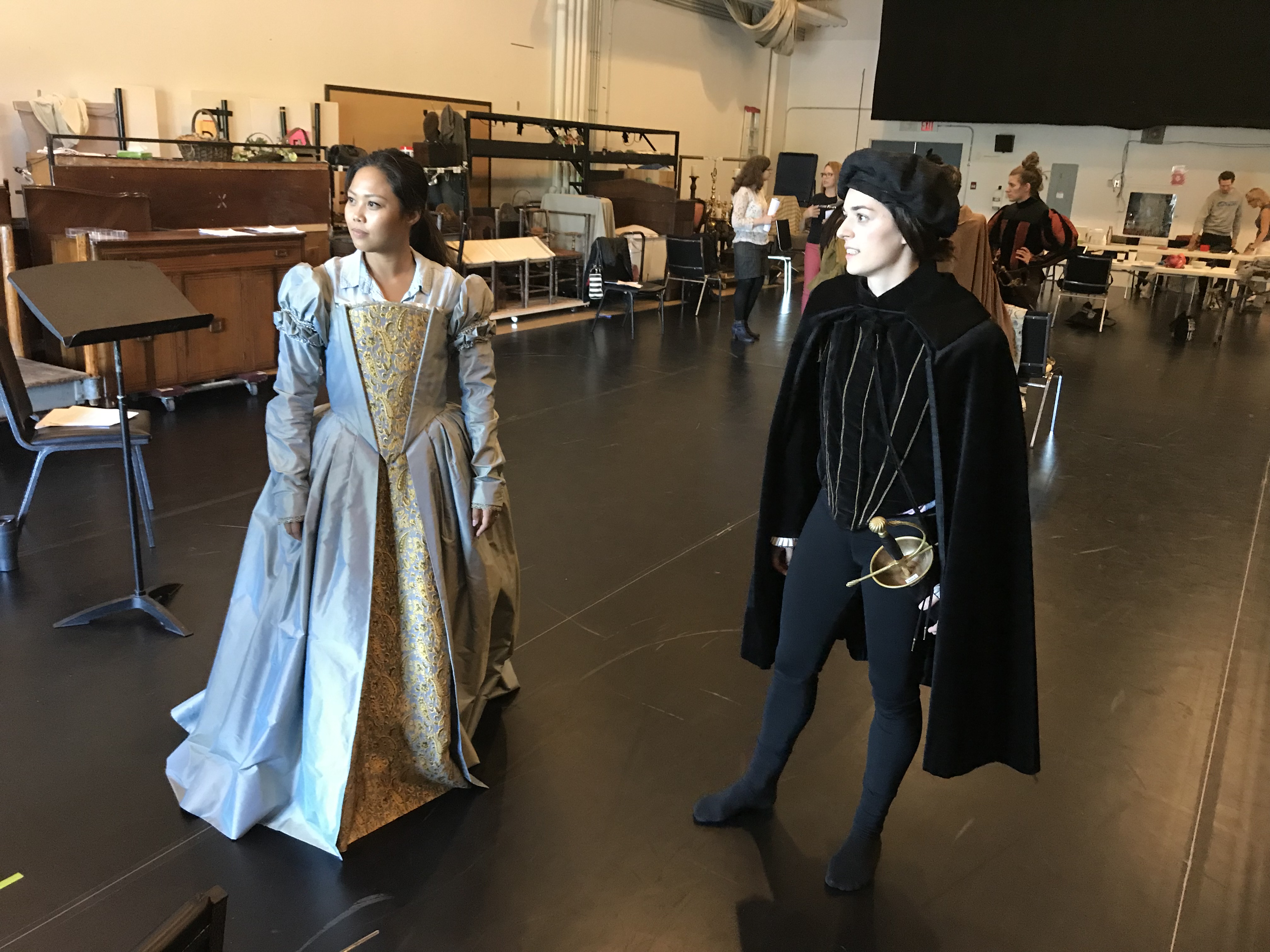

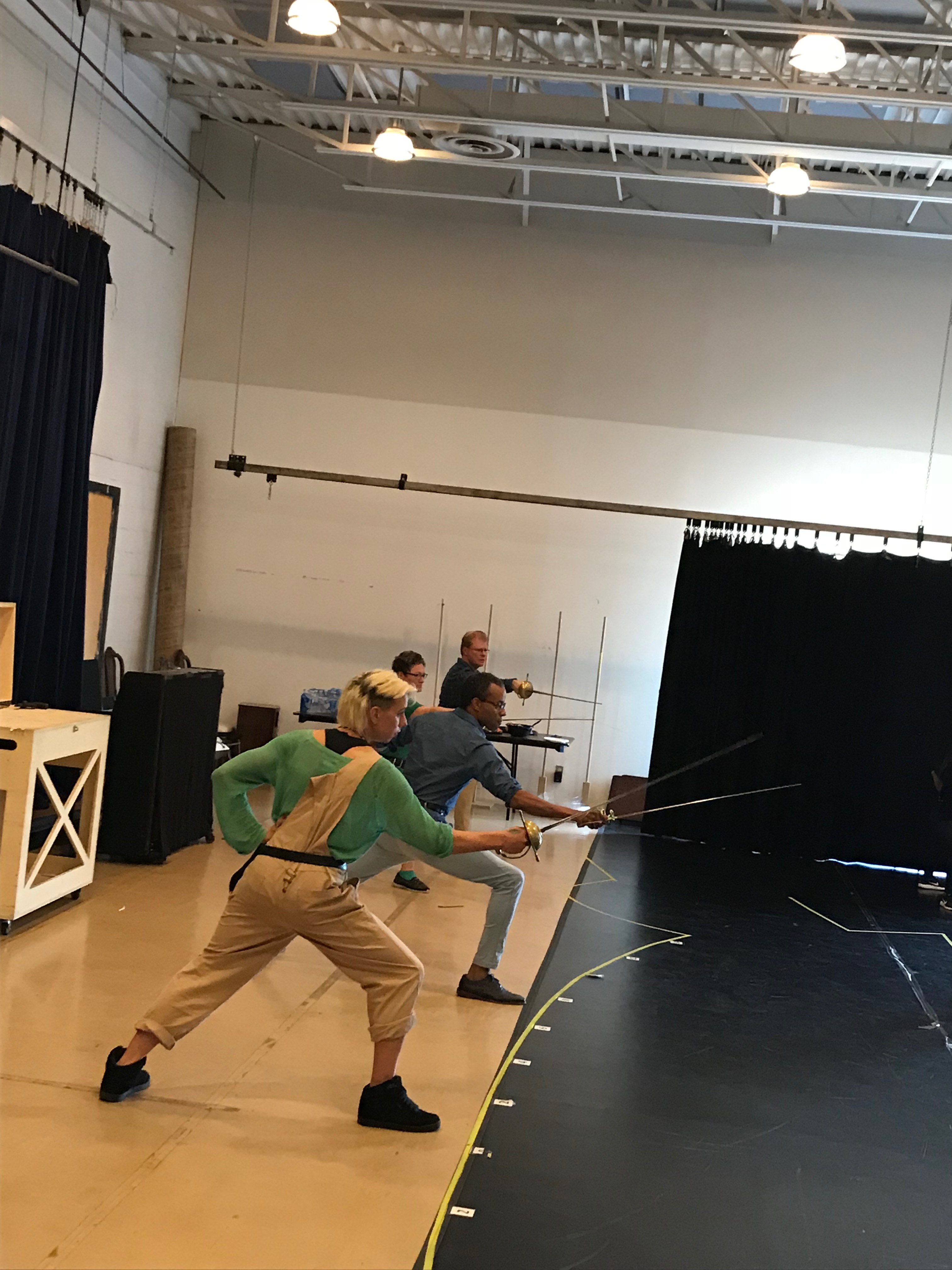

We began with the cross-dressing thief and performer Moll Cutpurse, who sums up early modern England’s contradictory approach to gender and its performance. Both celebrated and censured, Moll is most famous for playing their lute and singing at the Fortune Theatre in 1611. While the epitaph on Moll’s grave genders them female, the poem also speculates that the ashes and dust inside would ‘perplex a Sadducee / Whether it rise a He or She / Or two in one, a single pair’. Much like Joan of Arc, Moll’s identity remains mutable even after their death, offering us space to consider early modern experiences of the non-binary.

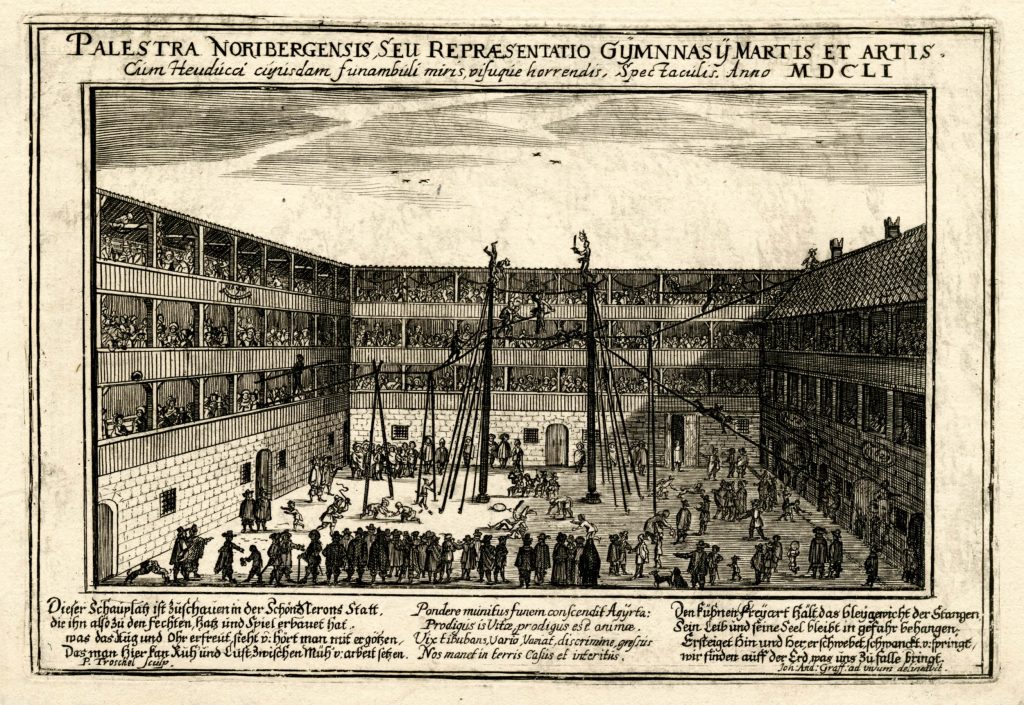

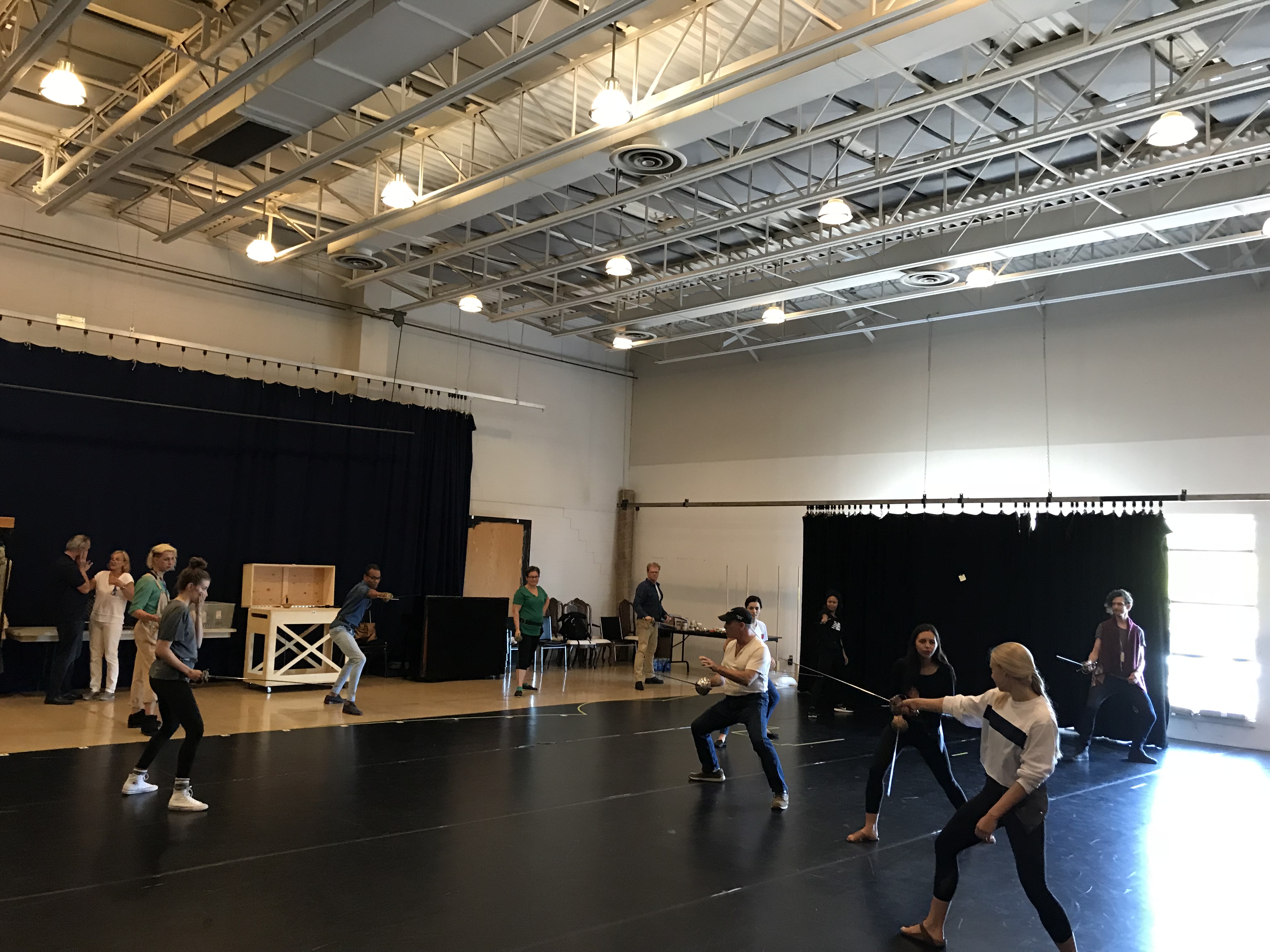

Rope-dancers often performed in the playhouses owned by the shareholders of the acting companies, including the Swan, the Hope, and the Red Bull. A surviving handbill from Bristol in the 1630s describes how ‘one Mayd of fifteene years of age, and another Girl of foure years of age doe dance on the lowe Rope’ and ‘turne on the Stage’. (Our thanks to Clare McManus for her brilliant work on this exciting area of early modern performance, which you can read more about in some of the suggested further reading below!) The youth and gender of these performers is important: just as young boys were recruited and apprenticed to the playing companies, children of all genders worked and performed across the country.

A Scottish “gentlewoman minstrel” was paid 2s in 1603 for performing in Carlisle. Both her gender and nationality distinguish her from the payments made to other musicians, but in every other respect, it seems they were paid the same. The description of “gentlewoman” is interesting: women who performed in public were often conflated with sex workers or deemed sexually available, so perhaps this label attempted to safeguard the reputations of both her and the event at which she performed. A blind harper was paid 12d in 1602 for a civic performance, also in Carlisle. While his disability is noted in the record of payments, his wages seem on a par with sighted musicians. This suggests that while he was not discriminated against with low pay for his disability, his skill was not considered worth extra renumeration despite his lack of sight.

Sometimes disability itself was the attraction: Adrian Provoe and his wife were granted a four day licence in Norwich in 1632 for her to ‘show diverse works &c done with her feet’. Provoe’s wife is not named, and is only mentioned in connection to her husband. Their relationship may have been a true and supportive partnership, or an exploitative and abusive one, or anywhere in between. The power differences between husbands and wives, the able-bodied and the disabled, are not preserved in the record.

Our discussion then moved on to how we might include evidence such as this, and the questions they raise, in the work the Globe does with schools and the public. This was a brave and honest discussion as we moved away from the historical detail to more challenging subjects such as how to broach the racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia of the period, while acknowledging these issues are still very present in our society.

Everyone participating in these sessions was asked to complete a very short survey at the beginning and end, consisting of just two questions. We were keen to learn how much knowledge and confidence participants had in discussing these issues before we ran the sessions, and if this changed because of the training. The responses were overwhelmingly positive – everyone’s knowledge about these issues, and their confidence in broaching them with the public and education groups they worked with had risen. Some participants commented they appreciated the range of inclusive language that had been offered during the session, giving them new tools and strategies to discuss these important historical moments with their students or tour groups.

The evidence of diverse performers and performance across early modern England is already before us: we just need to look for it.

Further reading

Printed resources

Astington, John, ‘Trade, Taverns, and Touring Players in Seventeenth-Century Bristol’, Theatre Notebook, 71.3 (2017), 161–68

Brown, Pamela Allen, ‘Why Did the English Stage Take Boys for Actresses?’, Shakespeare Survey, 70 (2017), 182–87

Brown, Pamela Allen, and Peter Parolin, eds., Women Players in England 1500 – 1660 (Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing, 2005)

Clare, Eli, Exile & Pride: Disability, Queerness, & Liberation 2nd edn (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2009)

Faye, Shon, The Transgender Issue: An Argument for Justice (London: Penguin, 2021)

Halberstam, Jack, Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018)

Heyam, Kit, Before We Were Trans: A New History of Gender (London: Hachette, 2022)

Korda, Natasha, Labors Lost: Women’s Work and the Early Modern English Stage (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011)

Loftis, Sonya Freeman, Shakespeare and Disability Studies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021)

Love, Genevieve, Early Modern Theatre and the Figure of Disability (London: Arden Bloomsbury, 2018)

McManus, Clare, “Sing it Like Poor Barbary’: Othello and Early Modern Women’s Performance’, Shakespeare Bulletin, 33.1 (2015), 99 – 120

McManus, Clare, ‘The Vere Street Desdemona: Othello and the Theatrical Englishwoman, 1602 – 1660’ in Women Making Shakespeare: Text, Reception and Performance eds. Gordon McMullan, Lena Cowen Orlin, & Virginia Mason Vaughan (London: Arden Bloomsbury, 2014), pp. 221 – 232

Nardizzi, Vin, ‘Disability Figures in Shakespeare’ in The Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare and Embodiment: Gender, Sexuality and Race ed. Valerie Traub (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 454–467

Non-Binary Lives: An Anthology of Intersecting Identities eds. Jos Twist, Meg-John Barker, Ben Vincent, & Kat Gupta (London: Jessica Kingsley, 2020)

Page, Nick, Lord Minimus: The Extraordinary Life of Britain’s Smallest Man (London: HarperCollins, 2001)

Schaap Williams, Katherine, Unfixable Forms: Disability, Performance, and the Early Modern English Theater (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2021)

Siebers, Tobin, ‘Shakespeare Differently Disabled’, in The Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare and Embodiment: Gender, Sexuality, and Race ed. Valerie Traub (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 434–454

Shakespeare, Tom, ‘The Social Model of Disability’ in ed. Lennard J. Davis, The Disability Studies Reader 5th edn (New York: Routledge, 2017), pp. 195 – 203

Whittlesey, Christy, The Beginners’ Guide to Being a Trans Ally (London: Jessica Kingsley, 2021)

Online resources:

Anderson, Susan, ‘Disability in Shakespeare’s England’, That Shakespeare Life, 2019

cassidycash.com/ep-76-susan-anderson-on-disability-in-shakespeares-england/

Bibby, Mariam, ‘Moll Cutpurse,’ Historic UK, 2019

historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Moll-Frith/

‘Disabled Shakespeares’, Disability Studies Quarterly, 2009

Davies, Callan, ‘Women and Early English Playhouse Ownership’, Engendering the Stage, 2018

Grange, S., ‘History, Queer Lives, and Performance’, A Bit Lit, 2020

youtube.com/watch?v=TrLFz5KzFJs

James, Susan, ‘Jane the Foole’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2019 oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-112276?rskey=sxtbPQ&result=2

Keywords for Disability Studies, NYU Press, 2021

keywords.nyupress.org/disability-studies/

Keywords for Gender and Sexuality Studies, NYU Press, 2021

keywords.nyupress.org/gender-and-sexuality-studies/

Lipscomb, Suzannah, ‘Disability in the Tudor Court’, Historic England

Marsden, Holly ‘Dangerous Women: Cross-dressing Cavalier Mary Frith’, Historic Royal Palaces, 2021 blog.hrp.org.uk/curators/dangerous-women-the-cross-dressing-cavalier-mary-frith/

McManus, Clare, ‘Feats of Activity and the Tragic Stage’, Engendering the Stage, 2019

engenderingthestage.humanities.mcmaster.ca/2019/04/30/feats-of-activity-and-the-tragic-stage/

McManus, Clare, ‘Shakespeare and Gender: The Woman’s Part’, British Library, 2016

bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/shakespeare-and-gender-the-womans-part

McManus, Clare, ‘Women Performers in Shakespeare’s Time’, Folger Shakespeare Library, 2019

folger.edu/shakespeare-unlimited/women-performers

Rackin, Phyllis, ‘The Hidden Women Writers of the Elizabethan Theatre’, The Atlantic, 2019

theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/06/shakespeares-female-contemporaries/590392/

Schaap-Williams, Katherine, ‘Richard III and the Staging of Disability’, British Library, 2016

bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/richard-iii-and-the-staging-of-disability

Shakespeare, Tom, ‘We need to talk about Charles I’s ‘pet dwarf”, Royal Academy, 2018

royalacademy.org.uk/article/charles-i-jeffrey-hudson-van-dyck-dwarf-tom-shakespeare

Thomas, Miranda Fay, ‘A Queer Reading of Twelfth Night’, British Library, 2016